Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

6.17--6.20

6.33, 6.40

8.24--8.25

\def \ititle {Logic I}

\def \isubtitle {Lecture 11}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}: \isubtitle

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

Readings refer to sections of the course textbook, \emph{Language, Proof and Logic}.

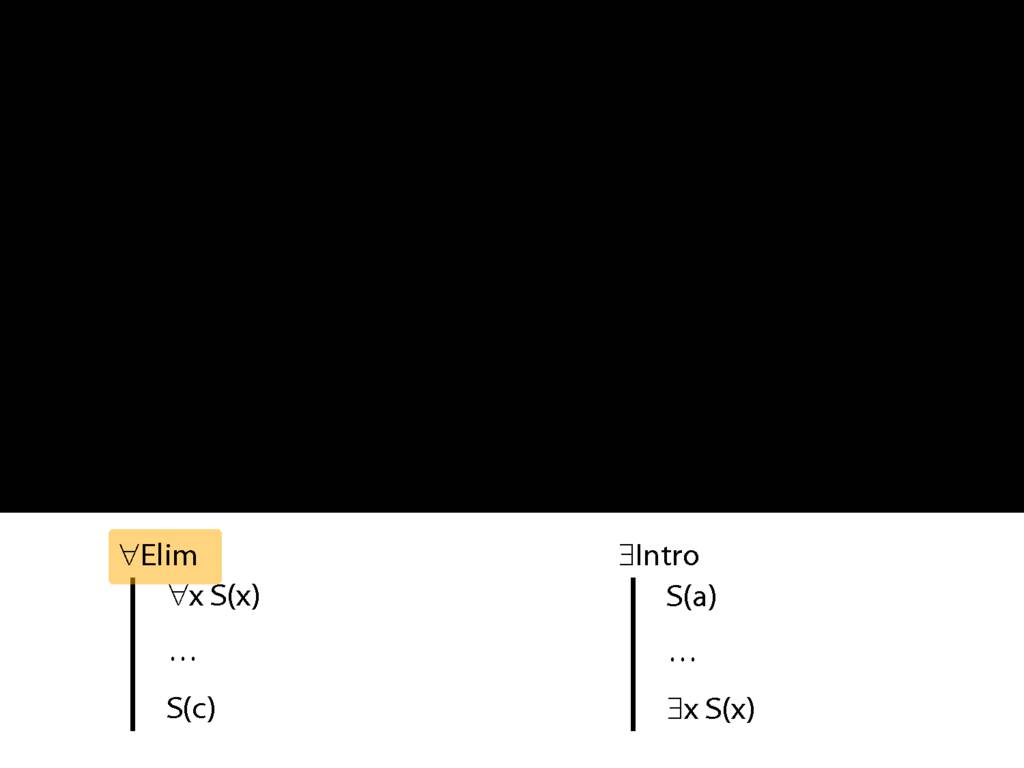

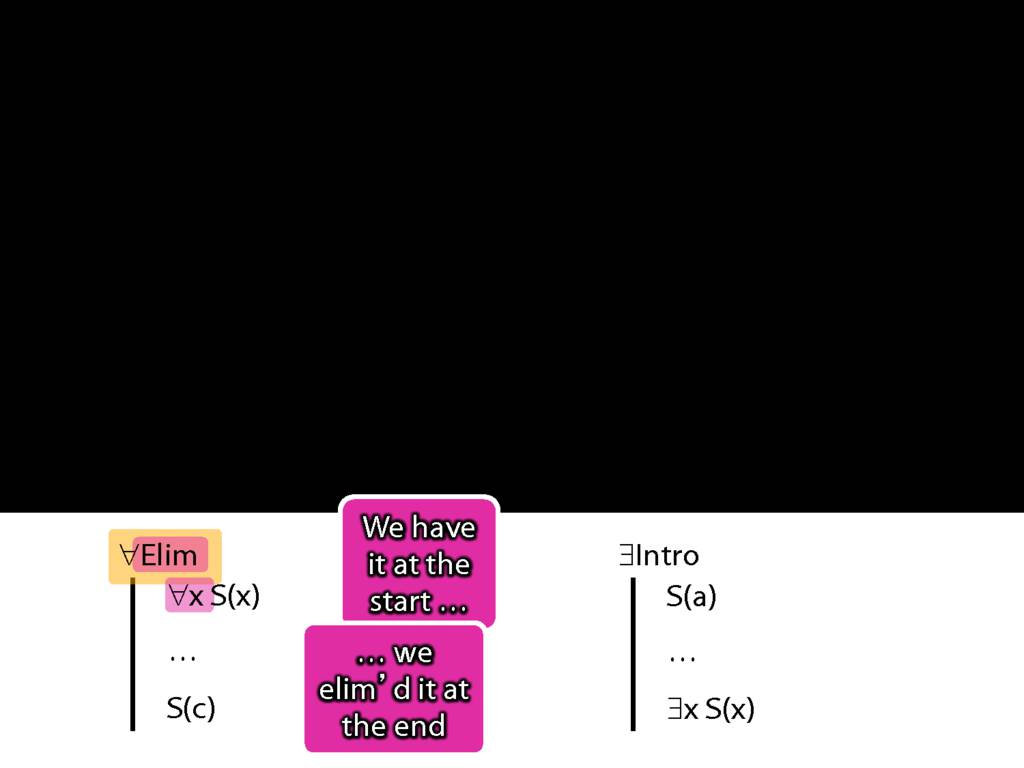

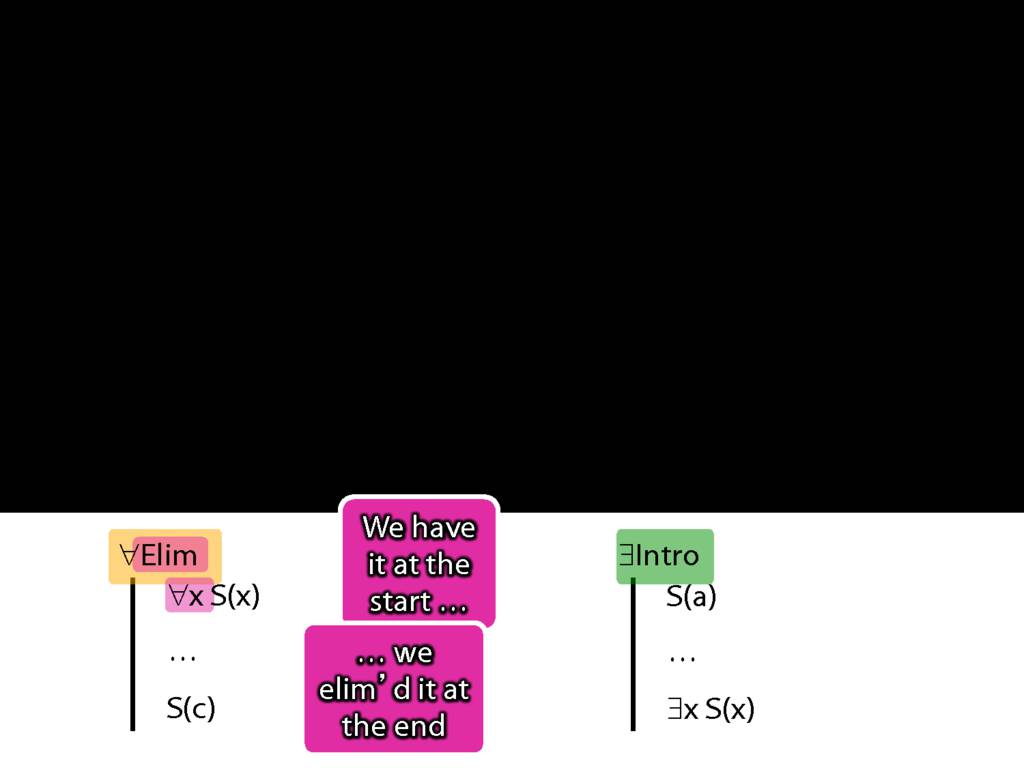

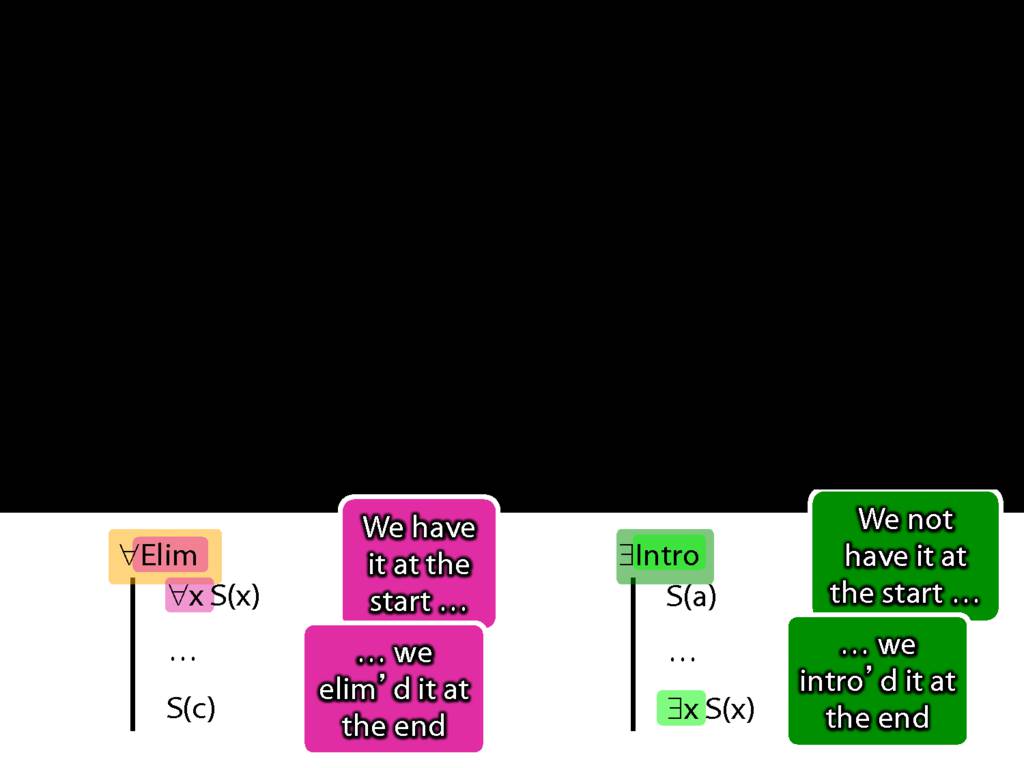

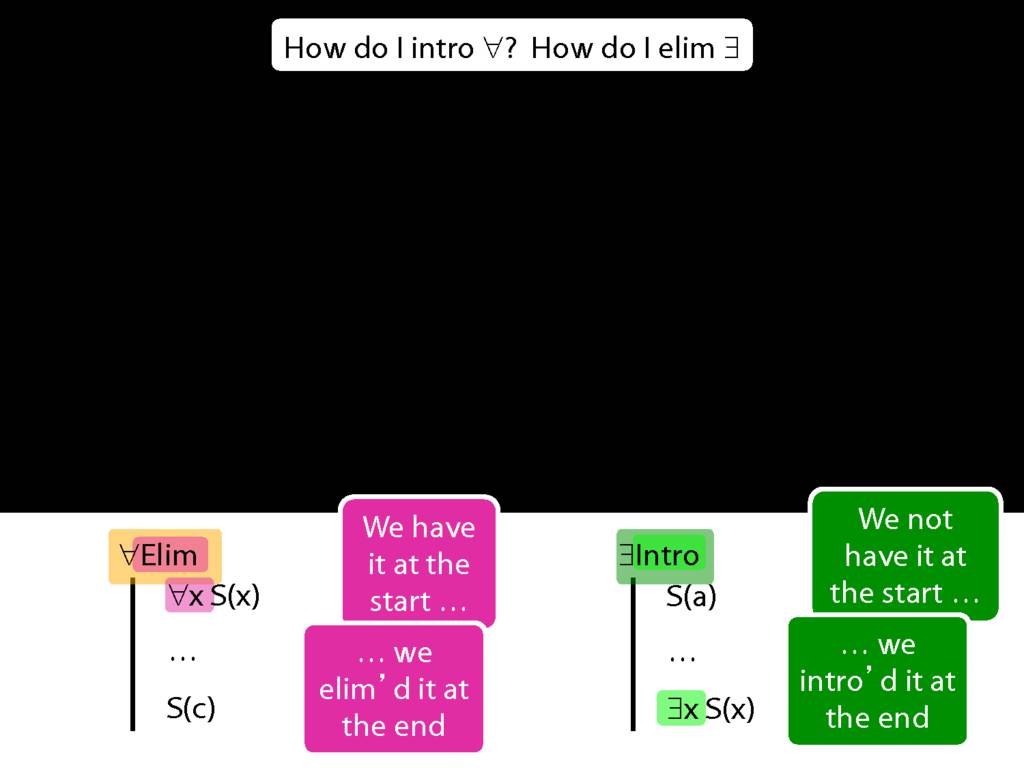

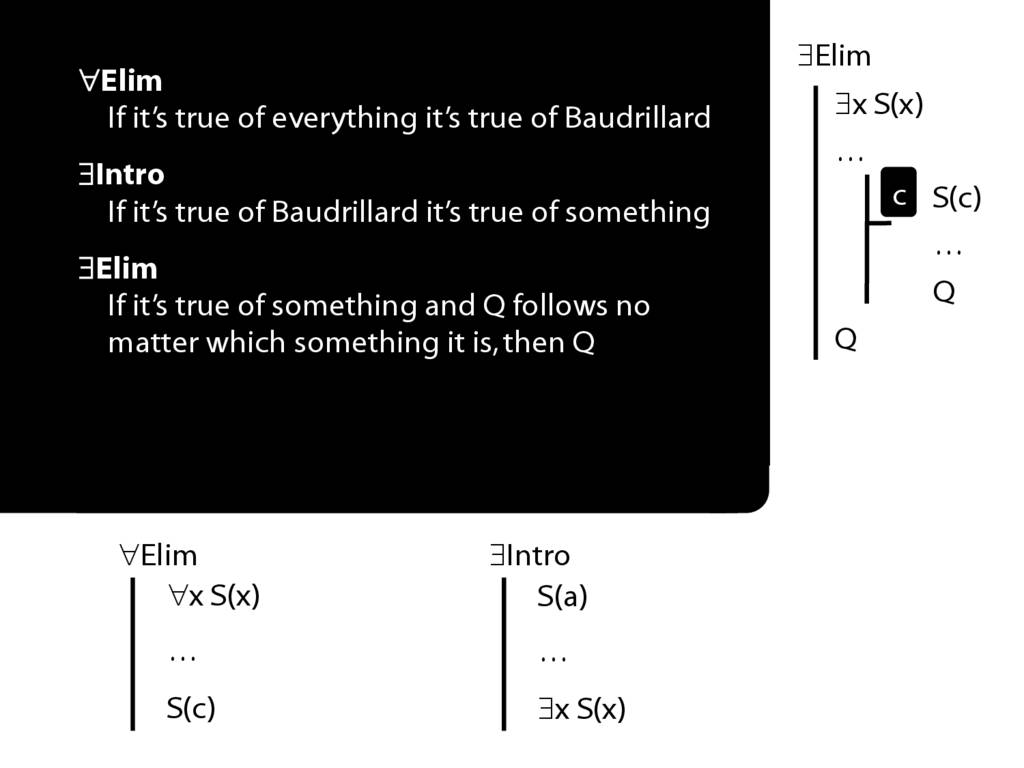

\section{Revision: ∀Elim, ∃Intro}

\emph{Reading:} §12.1, §13.1, §13.2

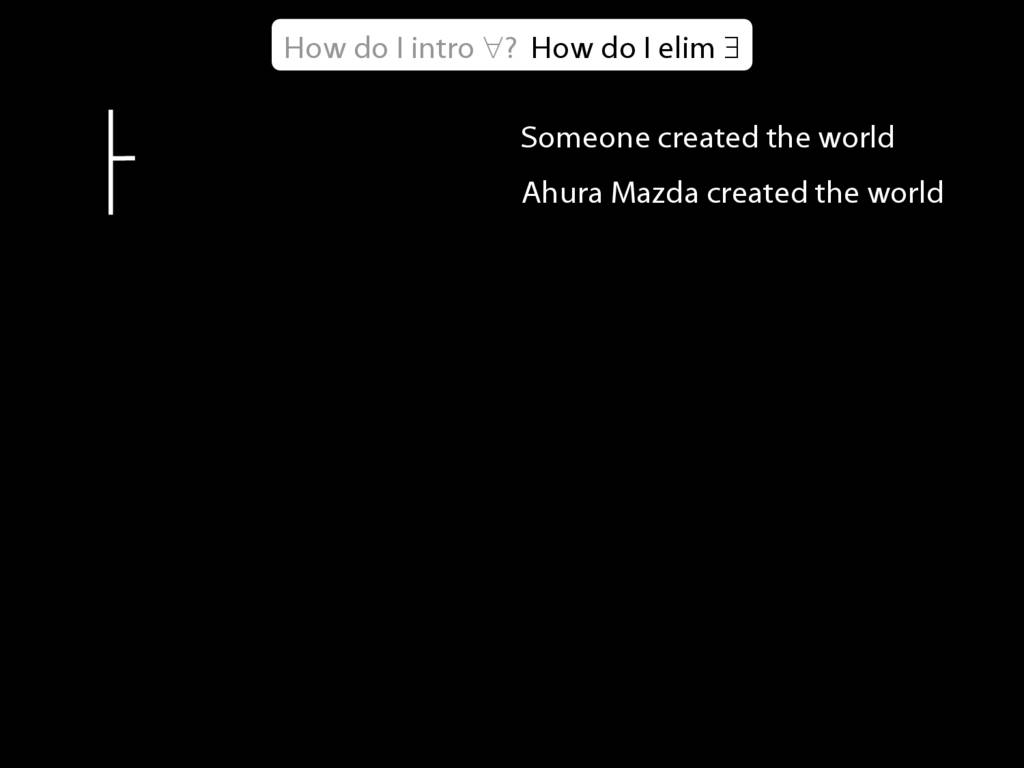

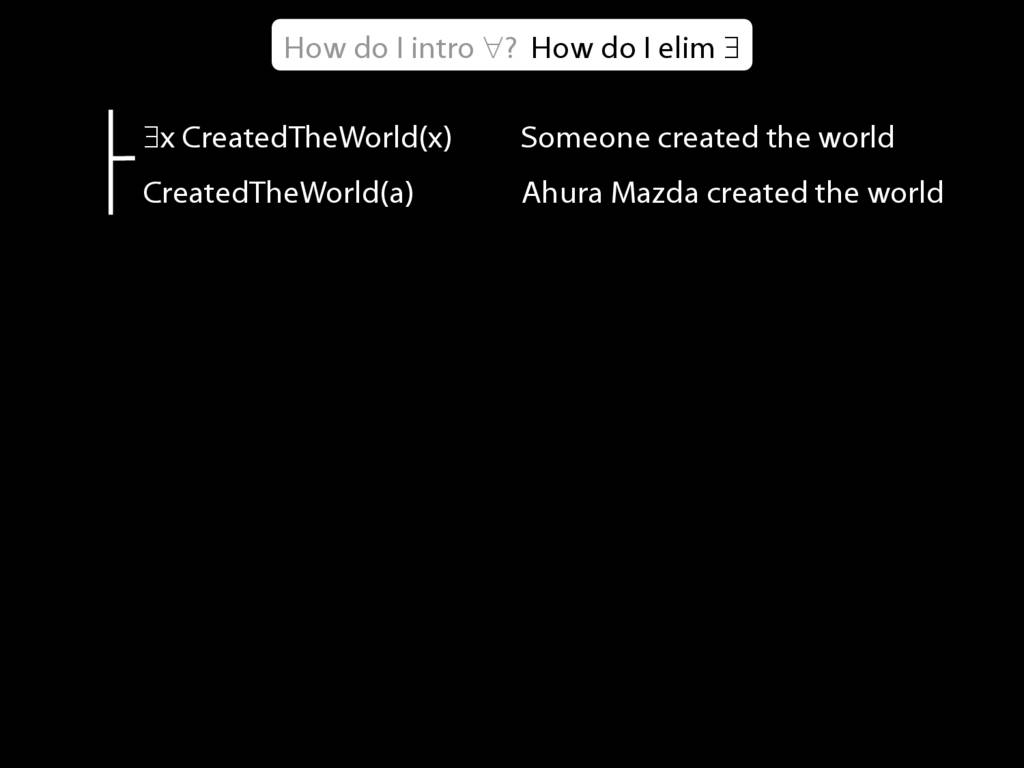

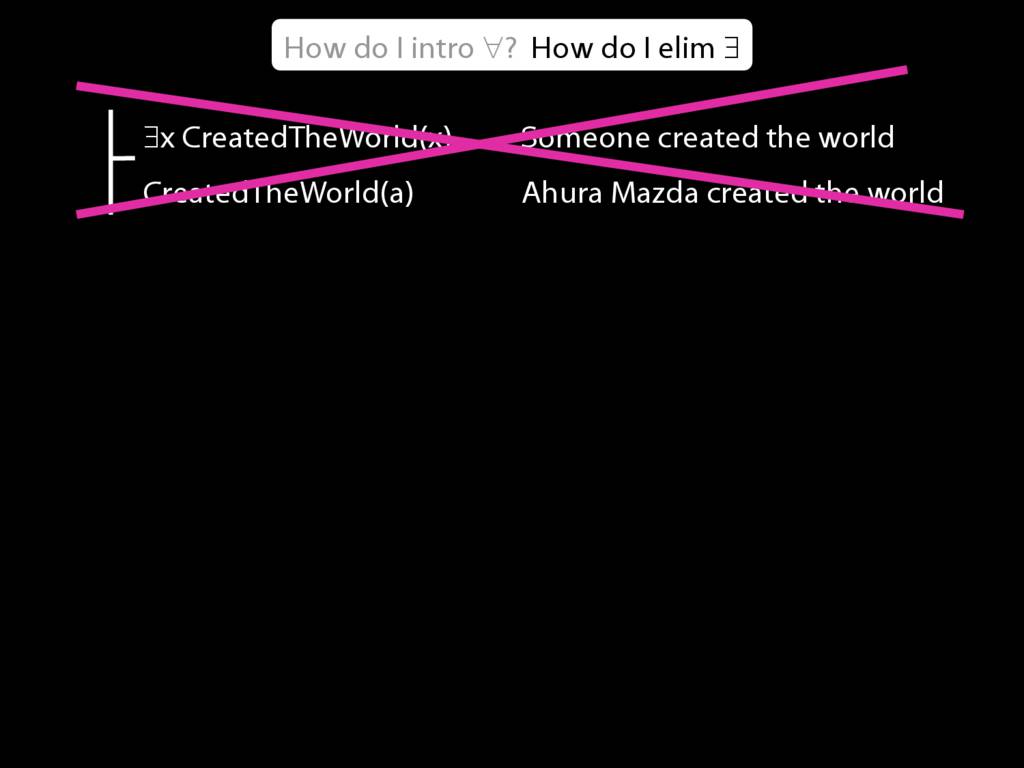

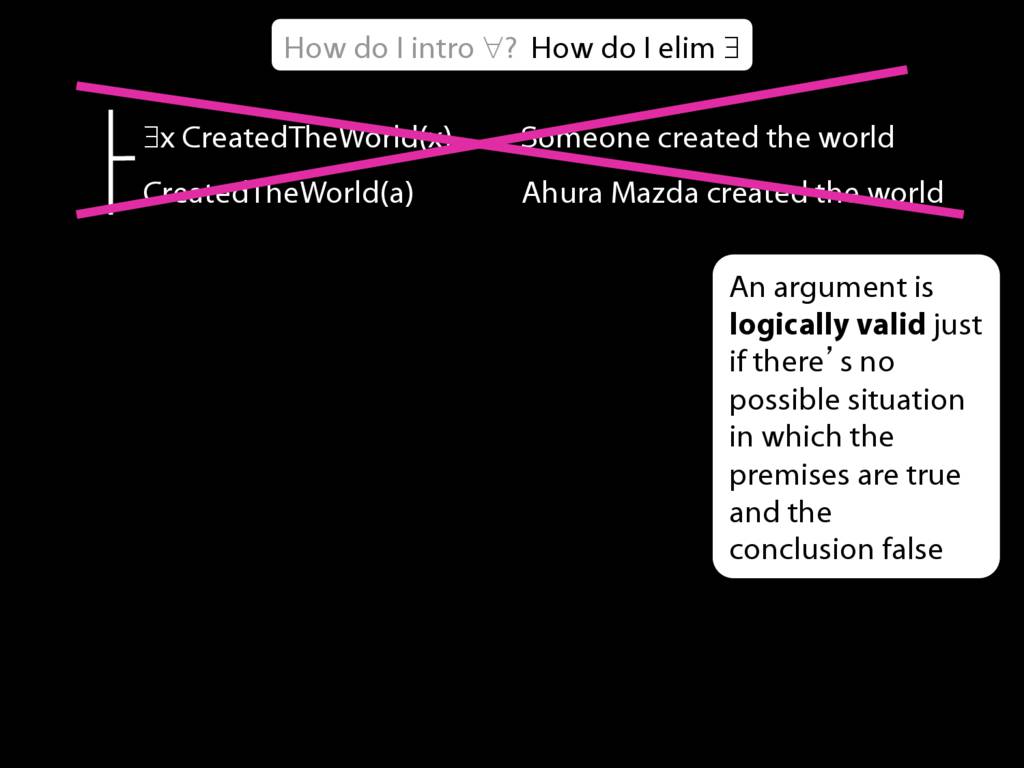

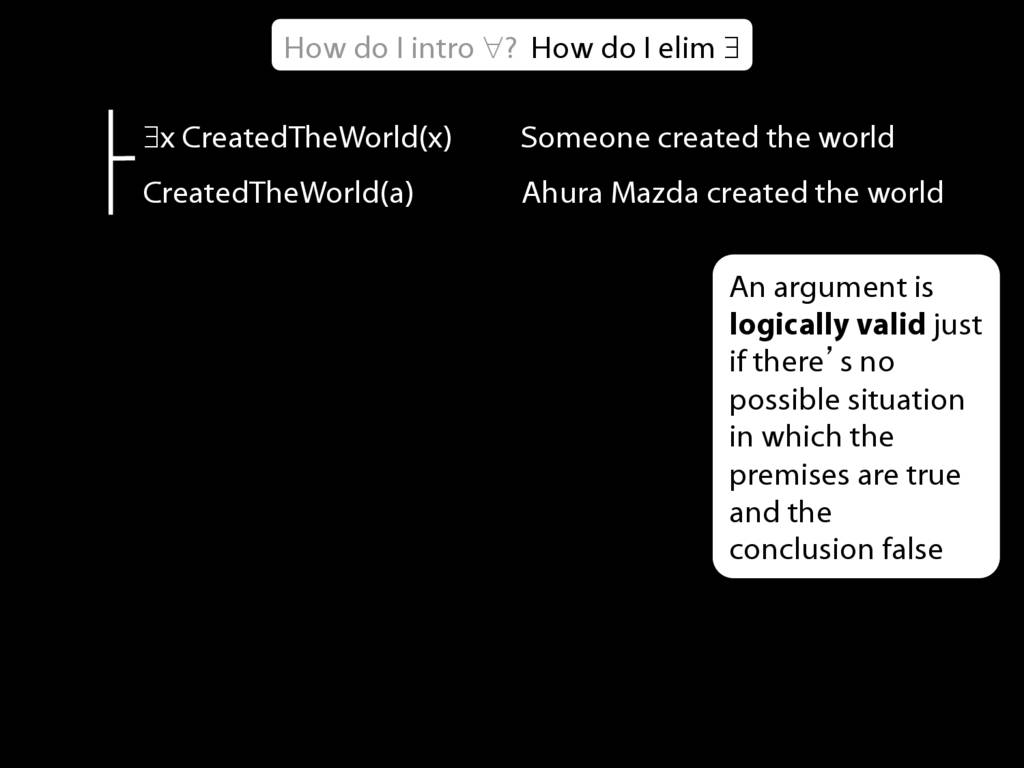

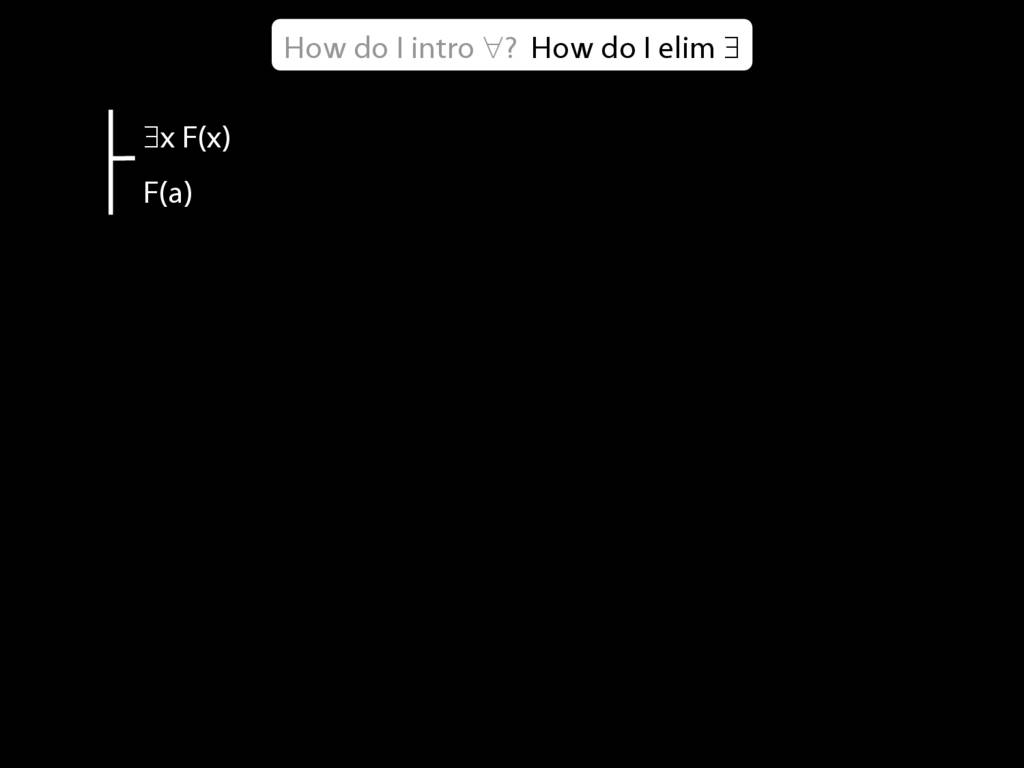

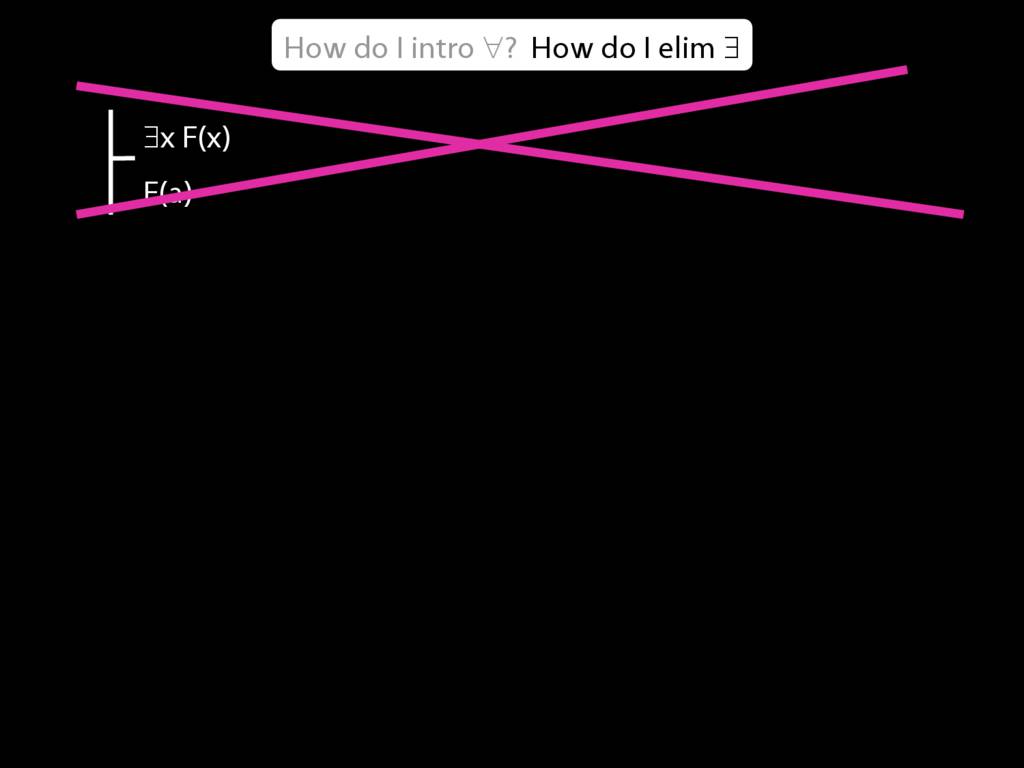

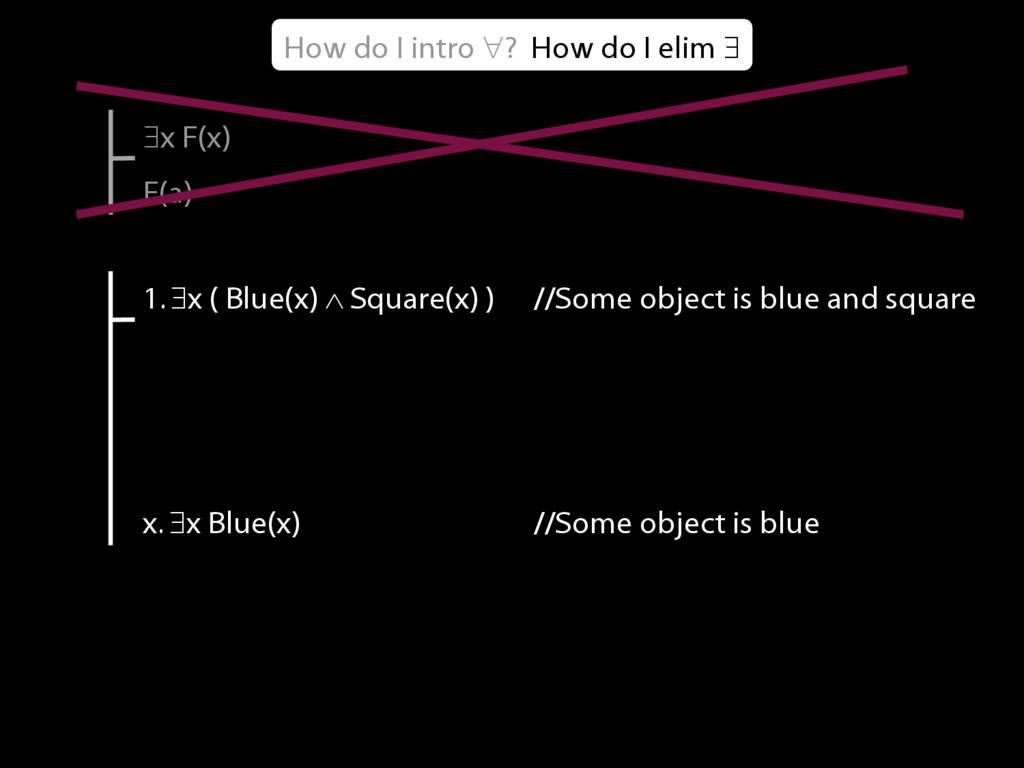

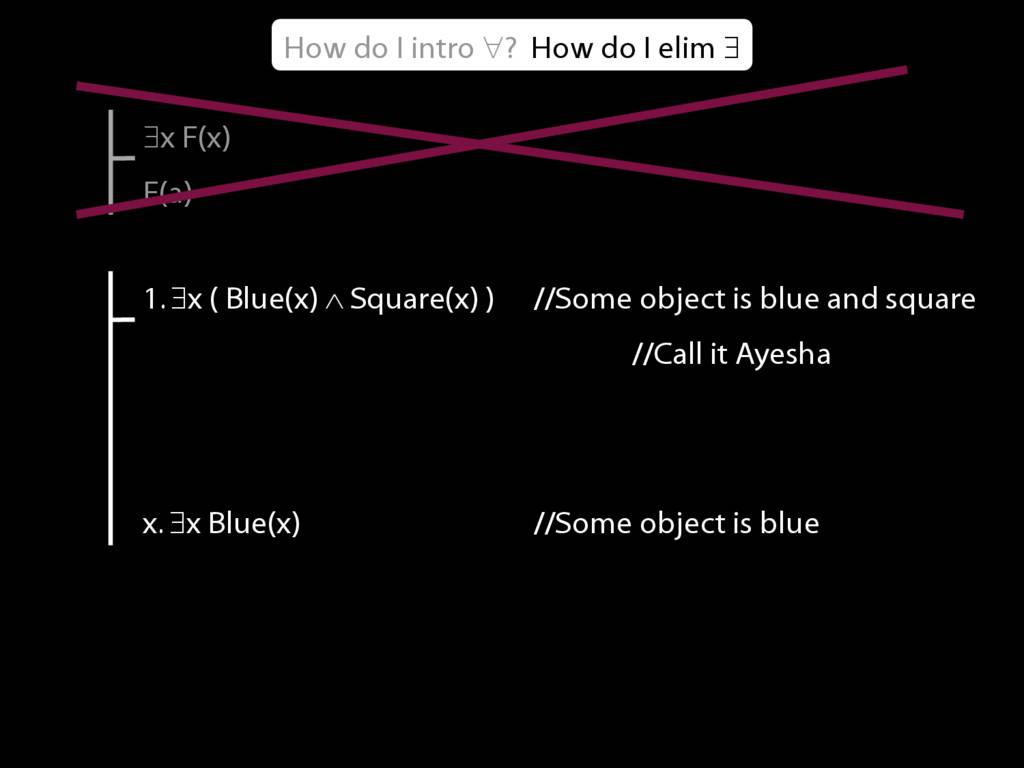

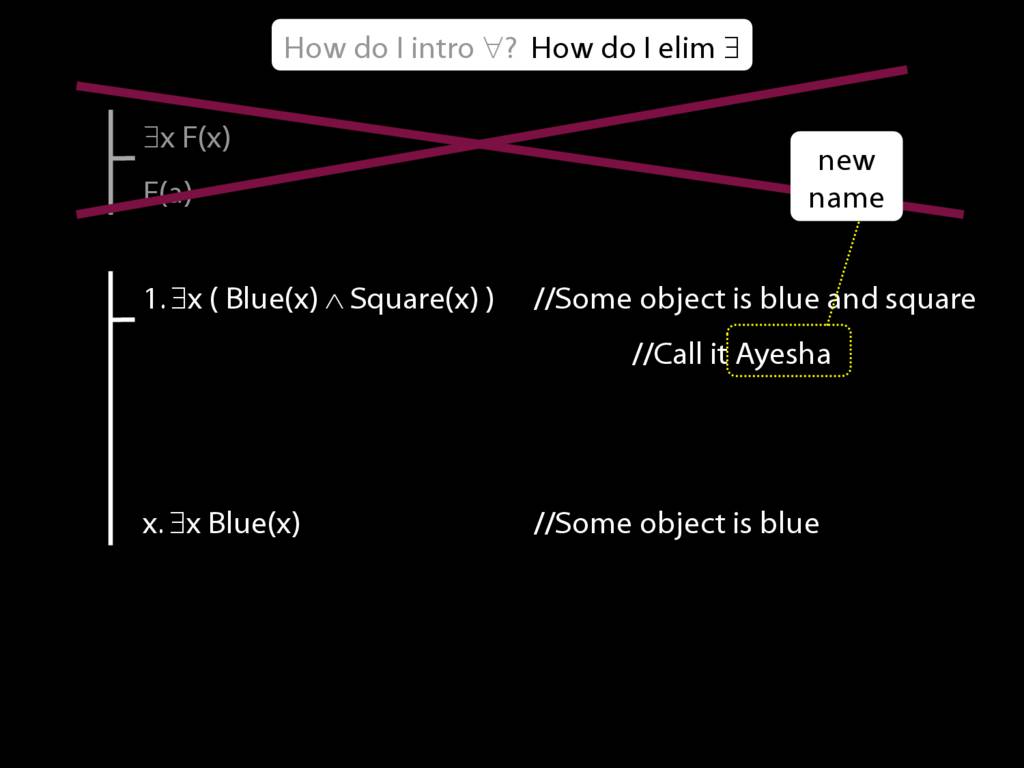

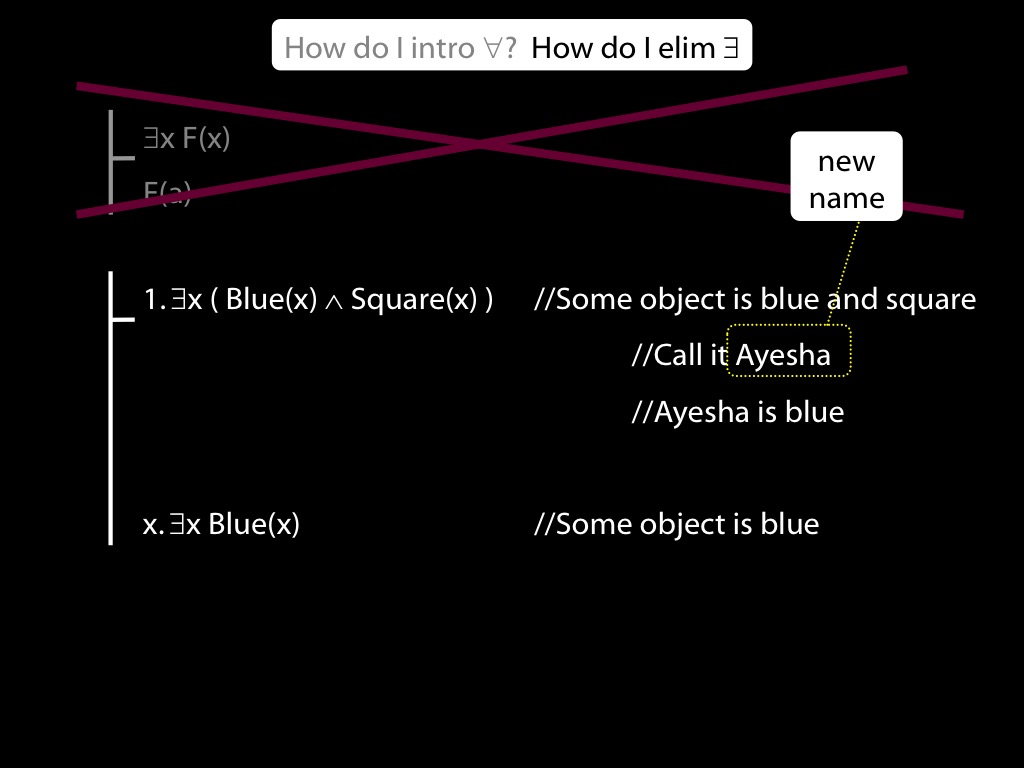

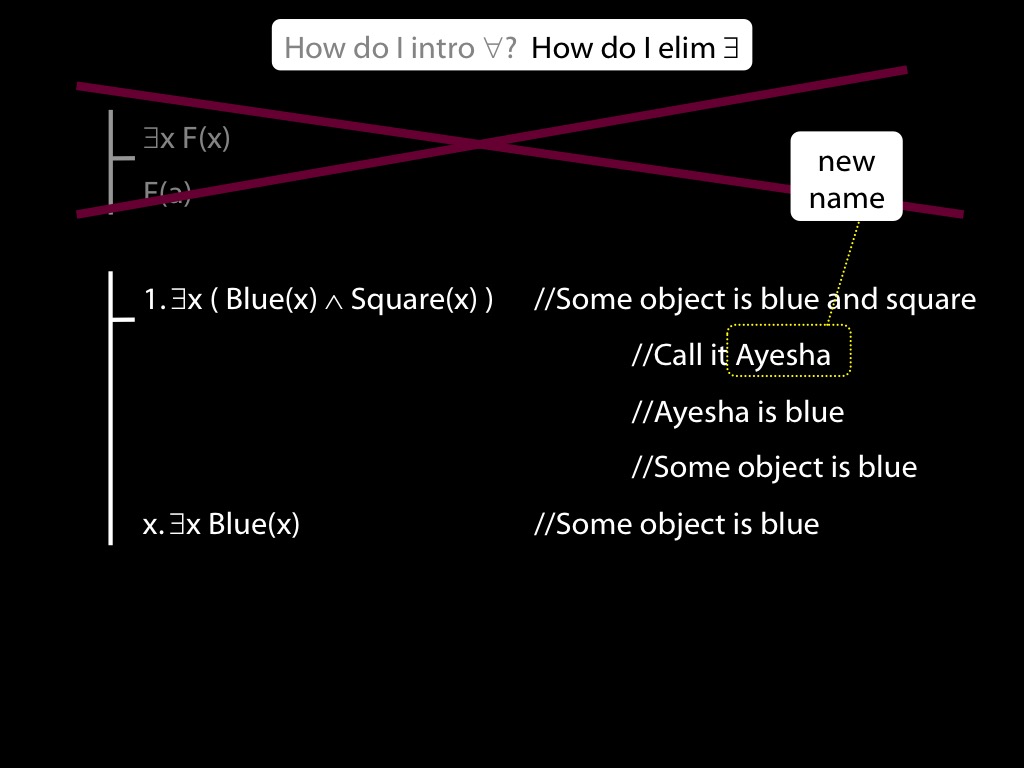

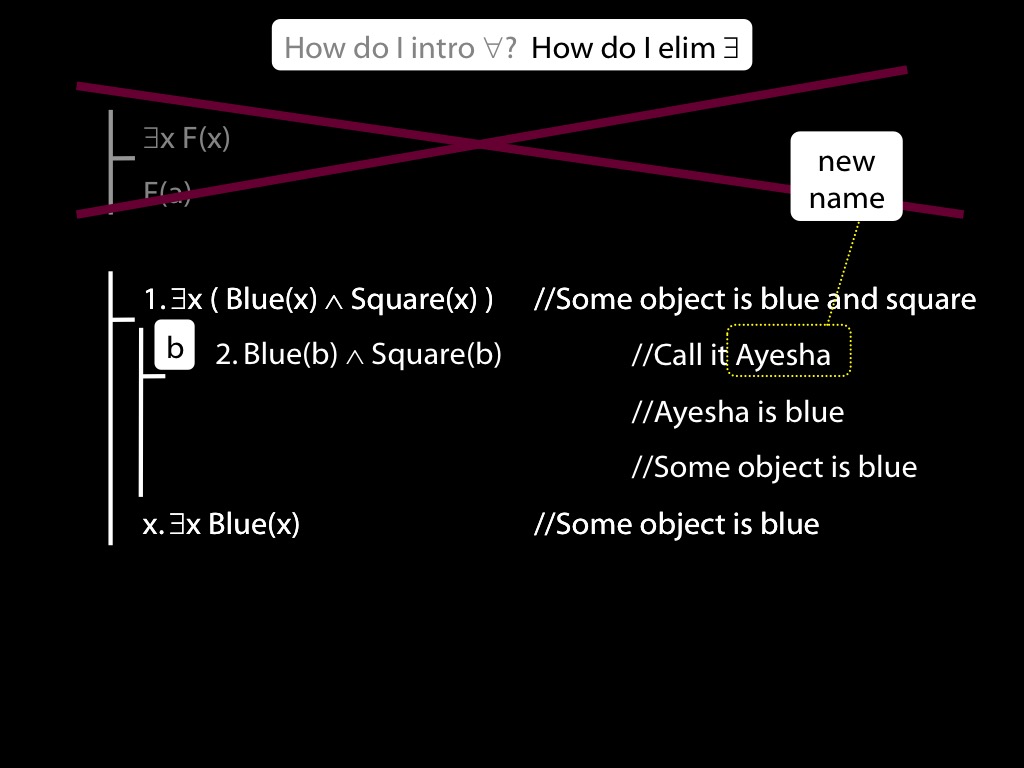

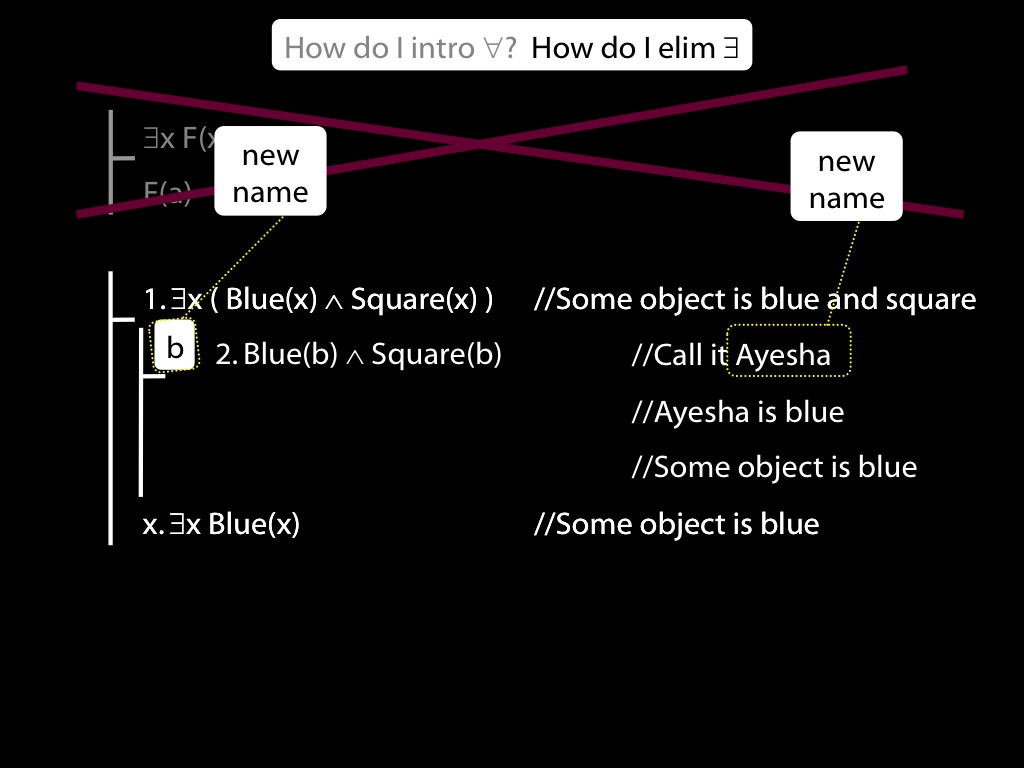

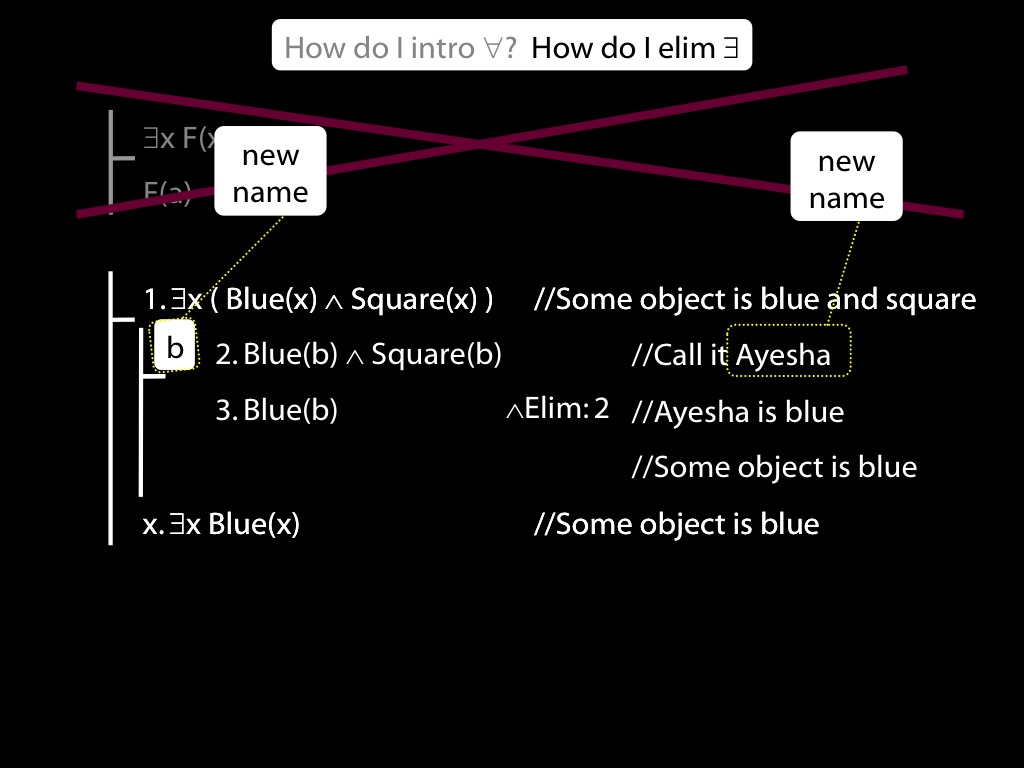

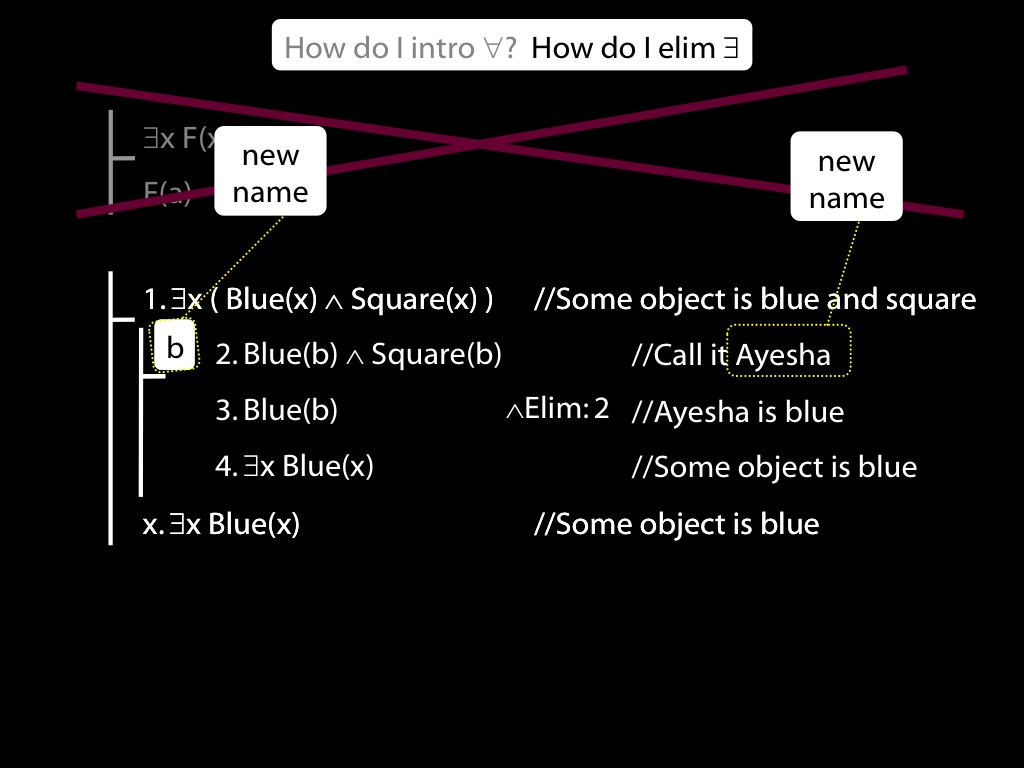

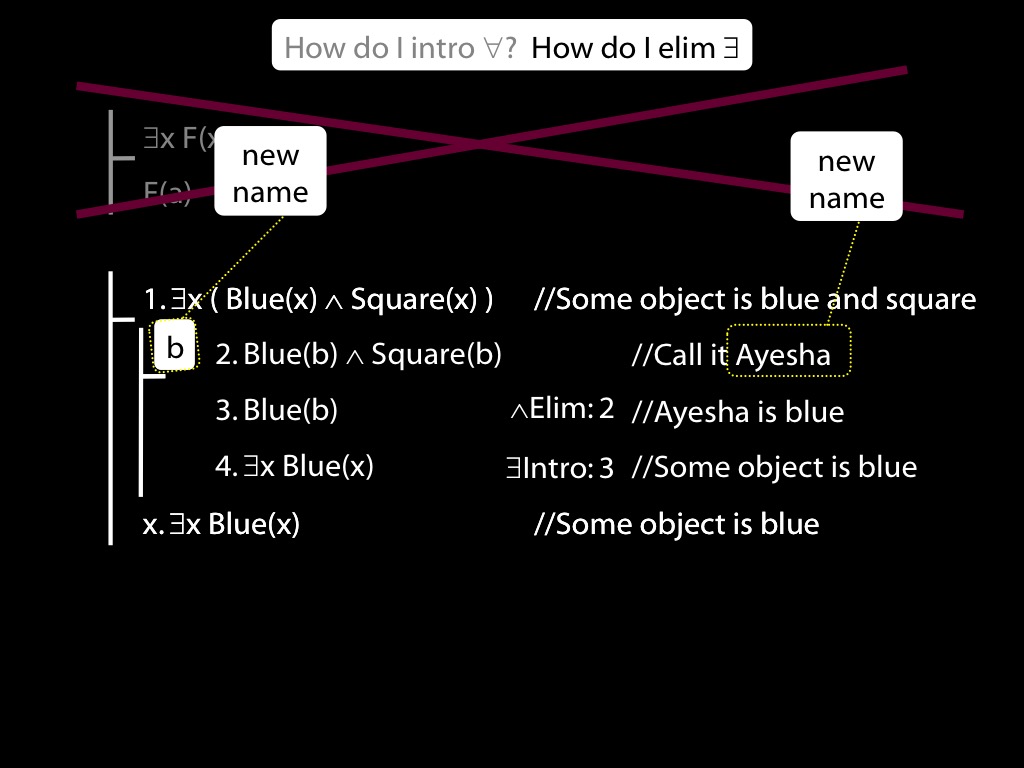

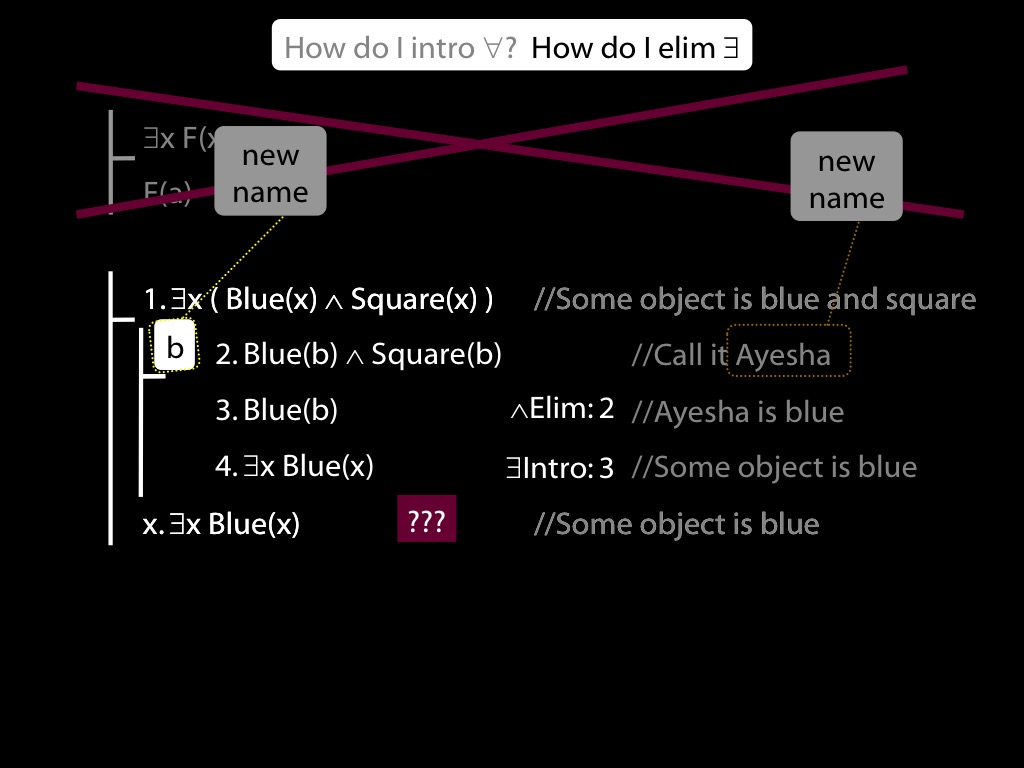

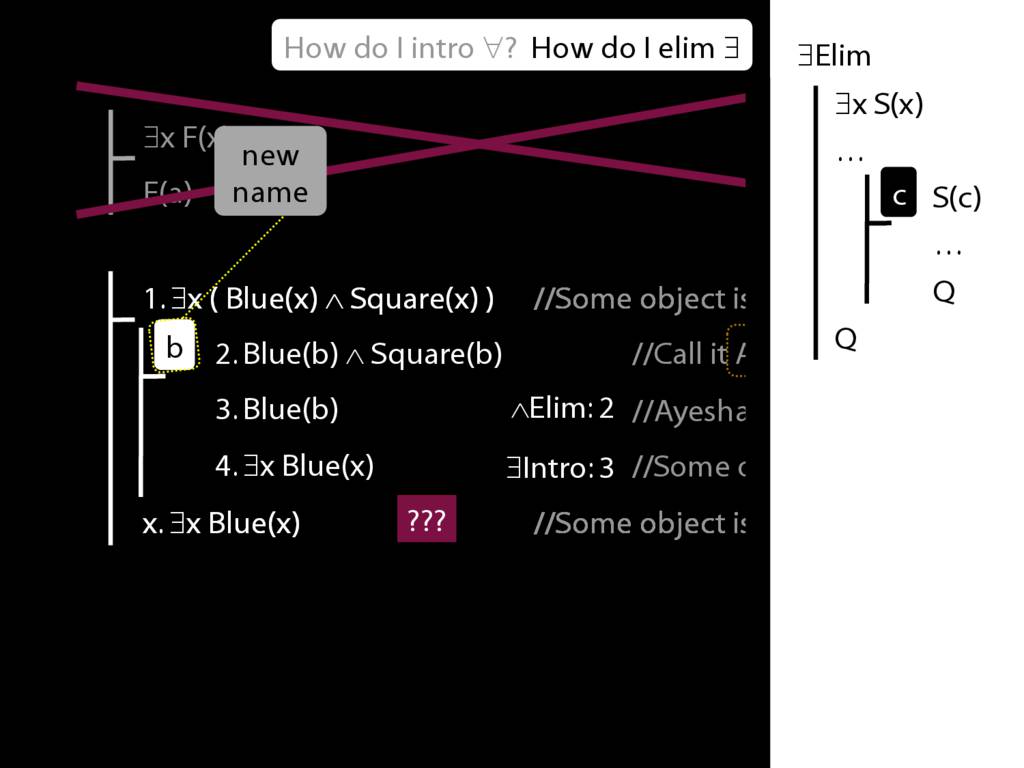

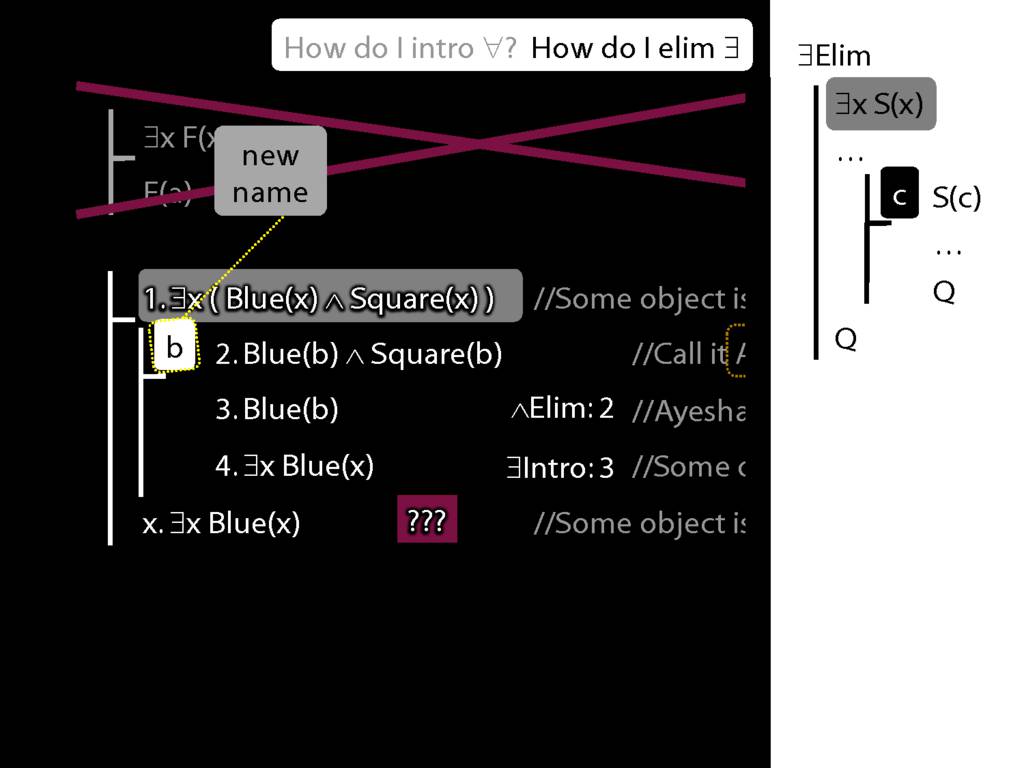

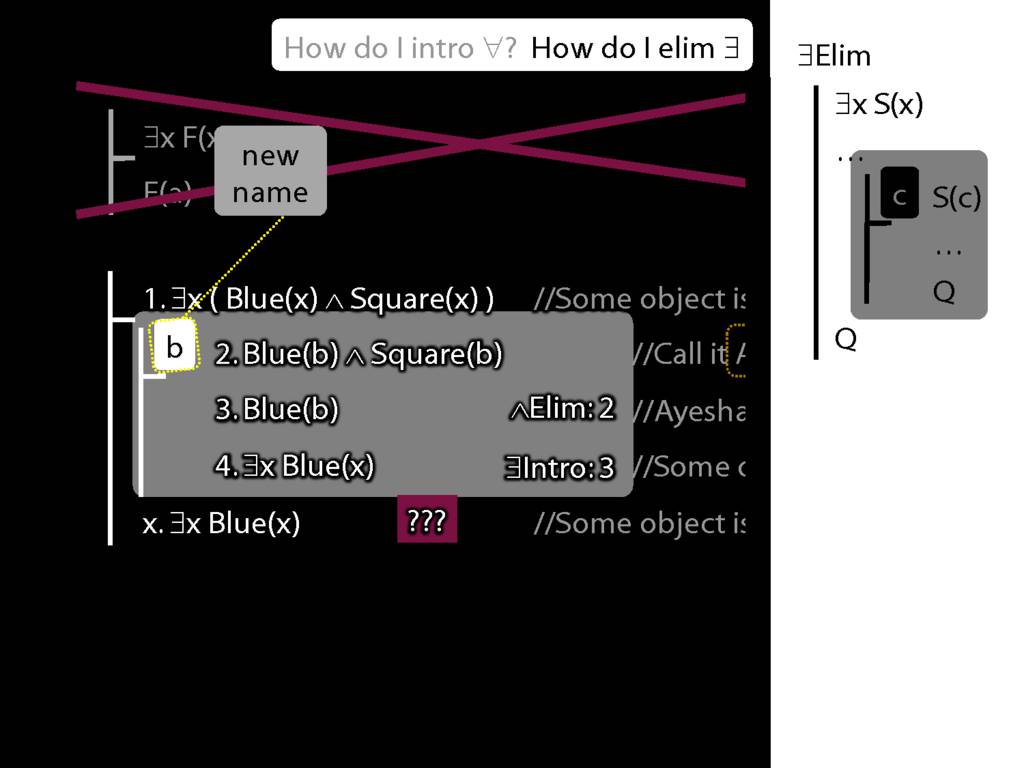

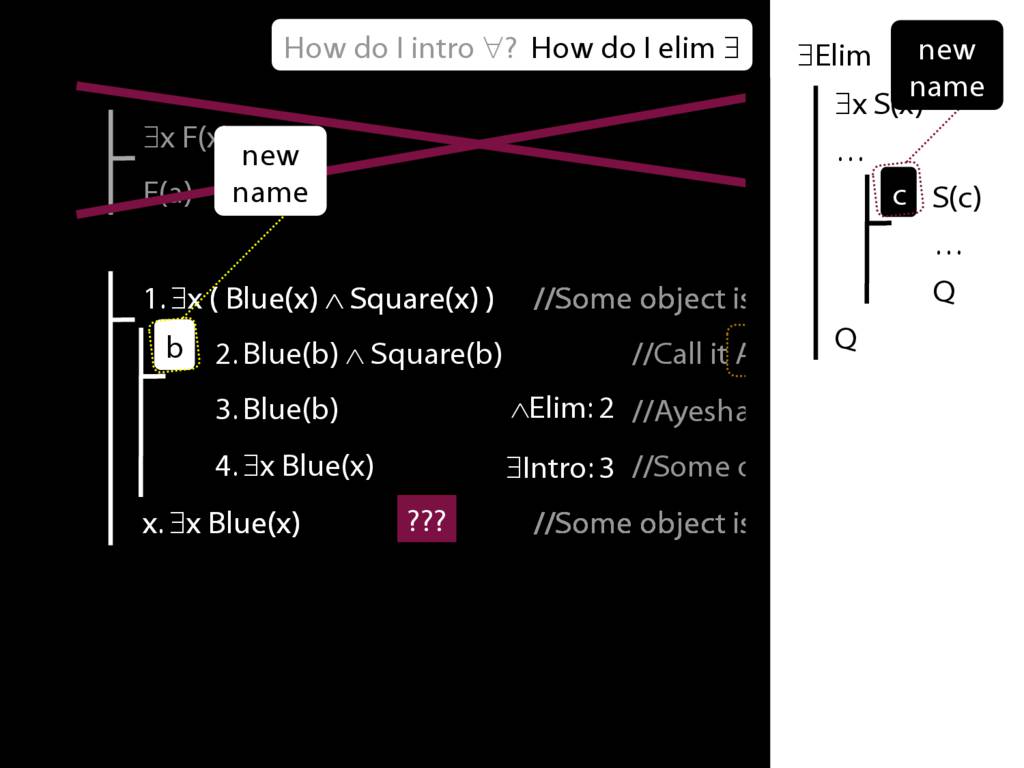

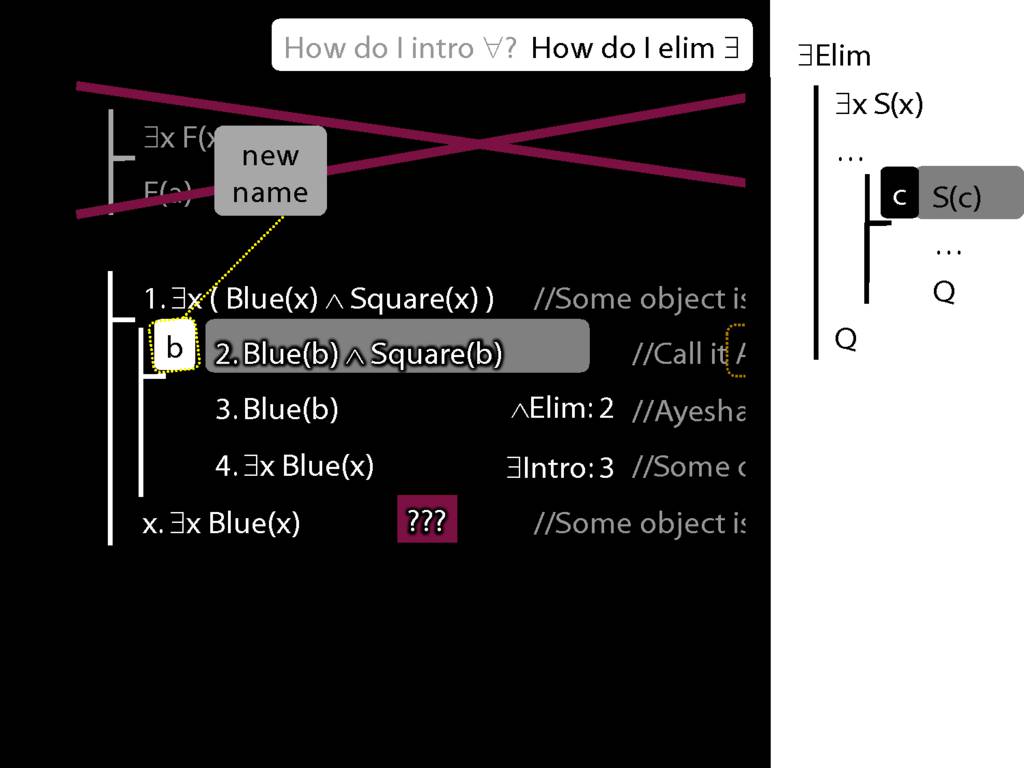

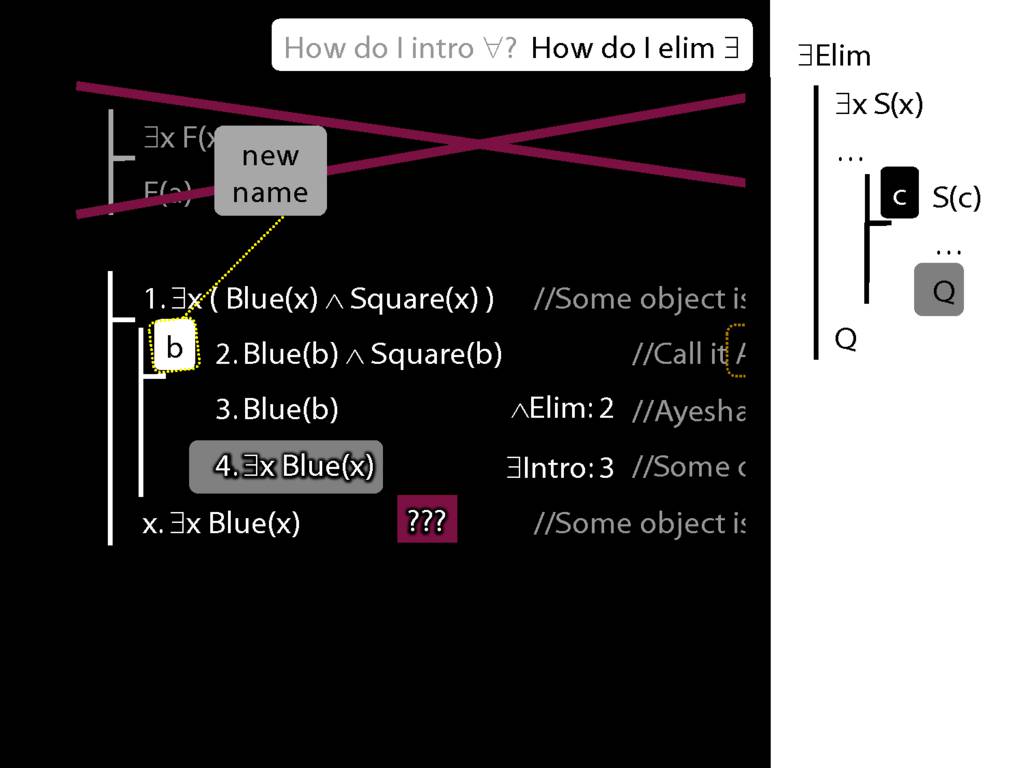

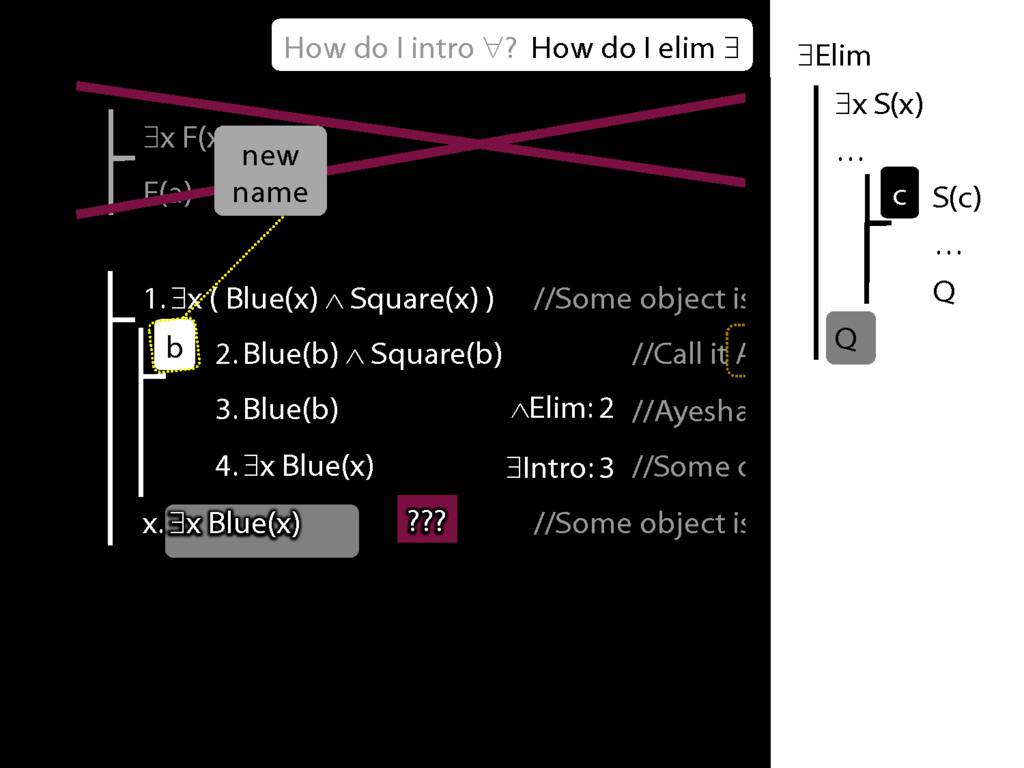

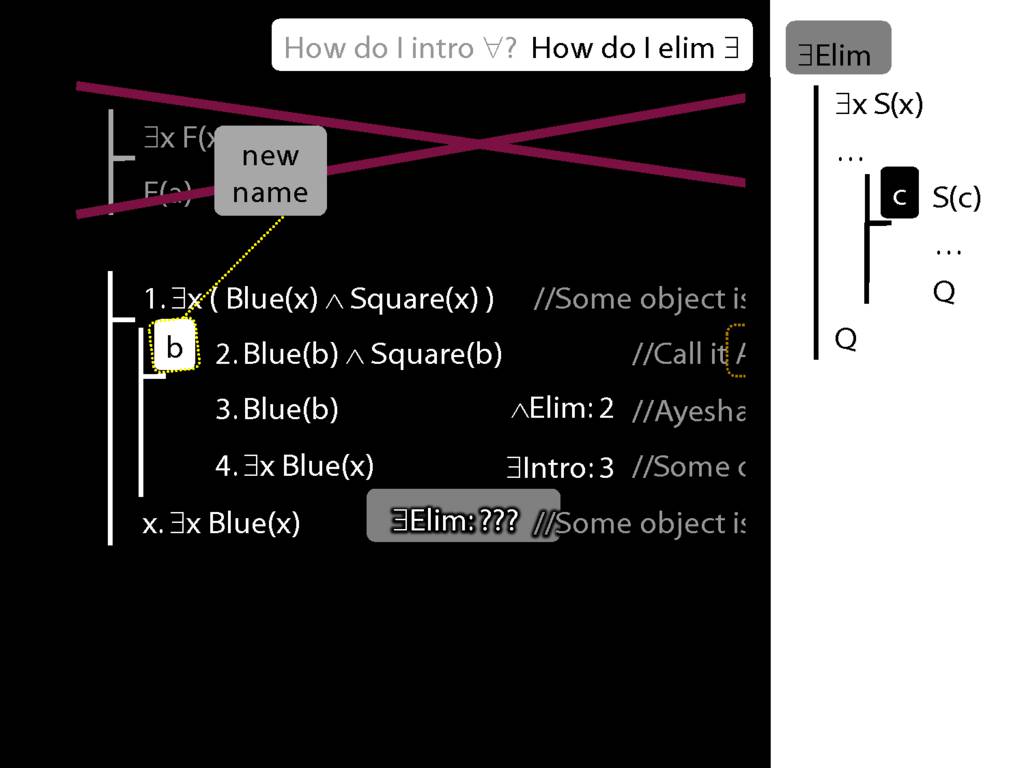

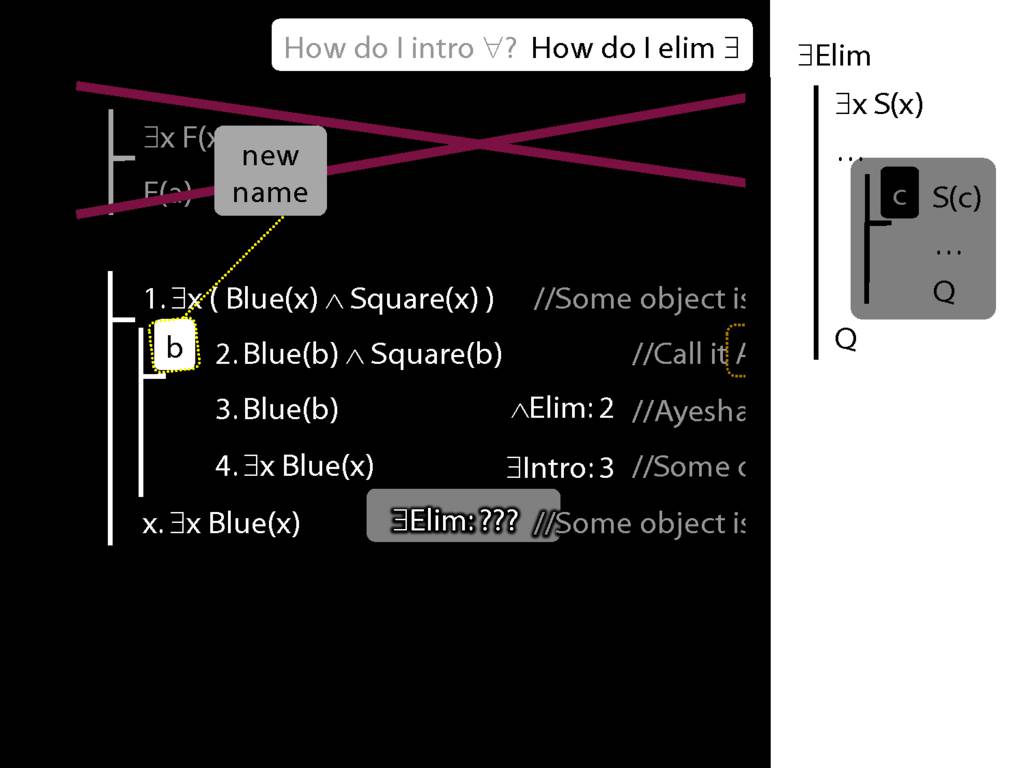

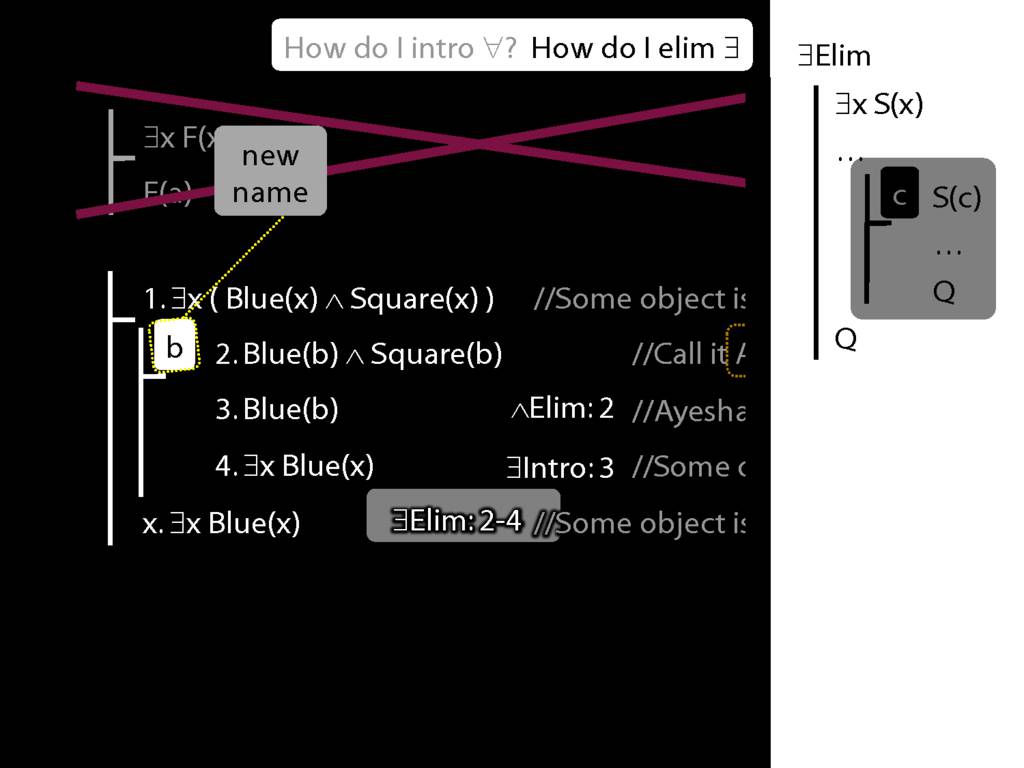

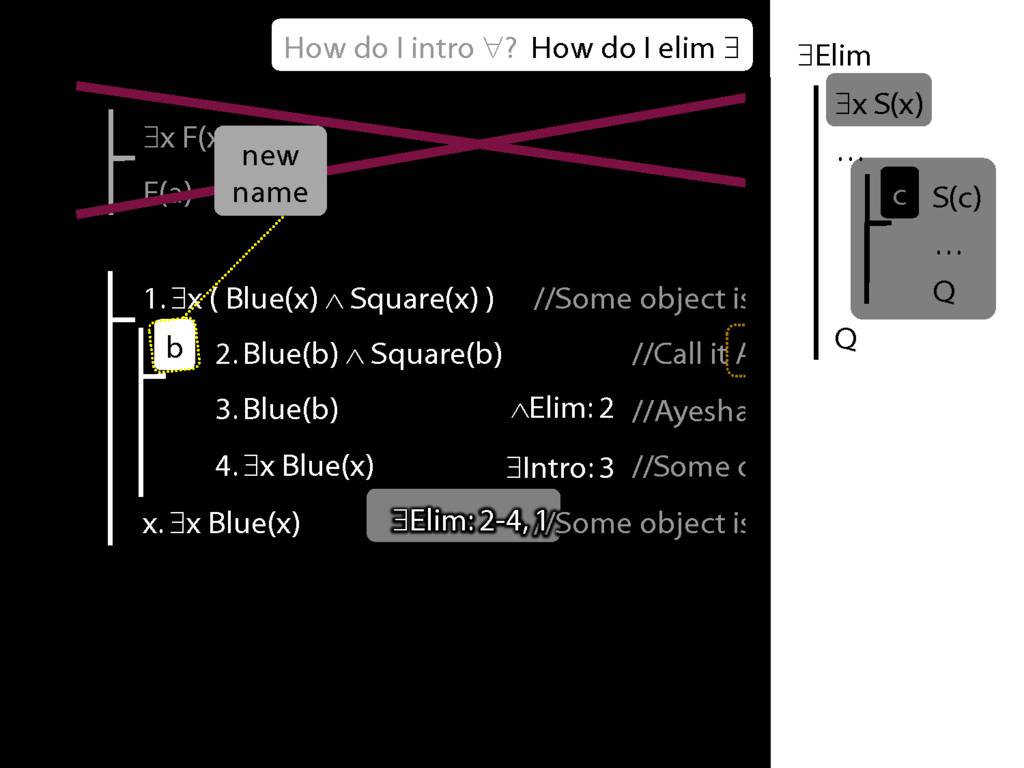

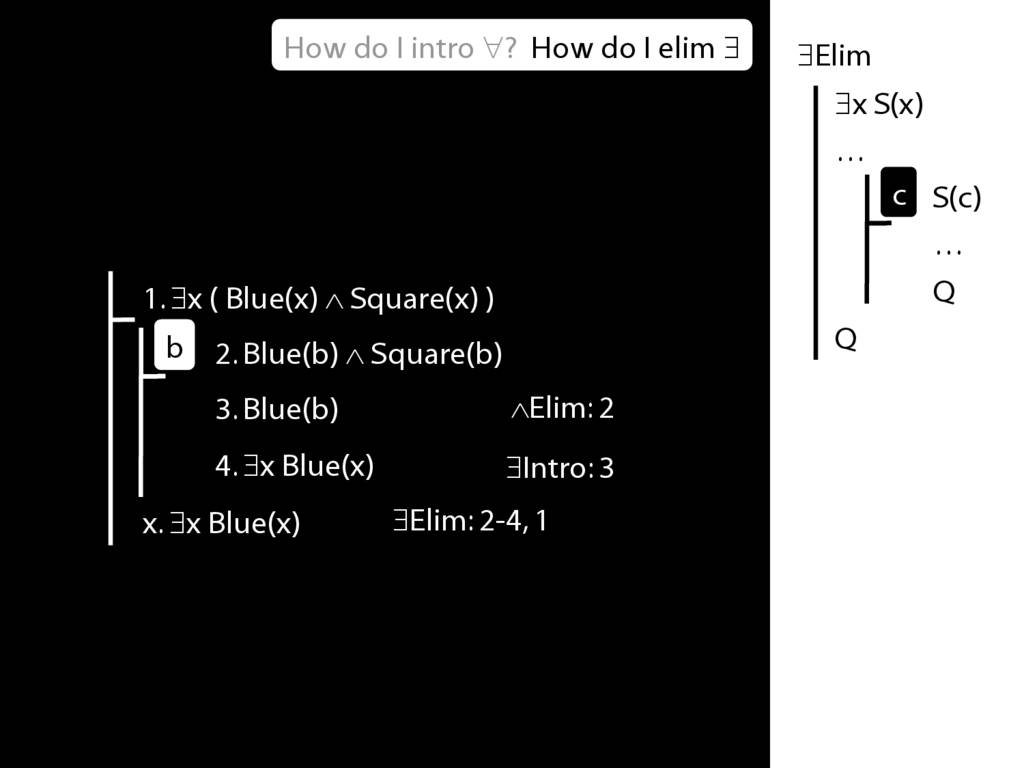

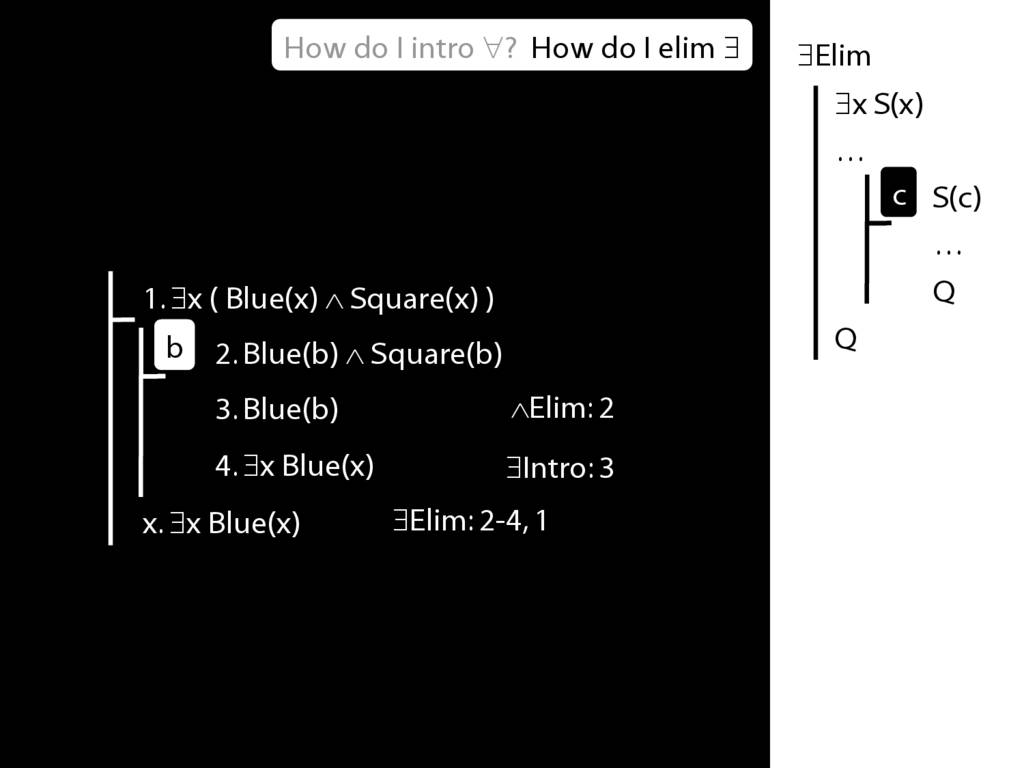

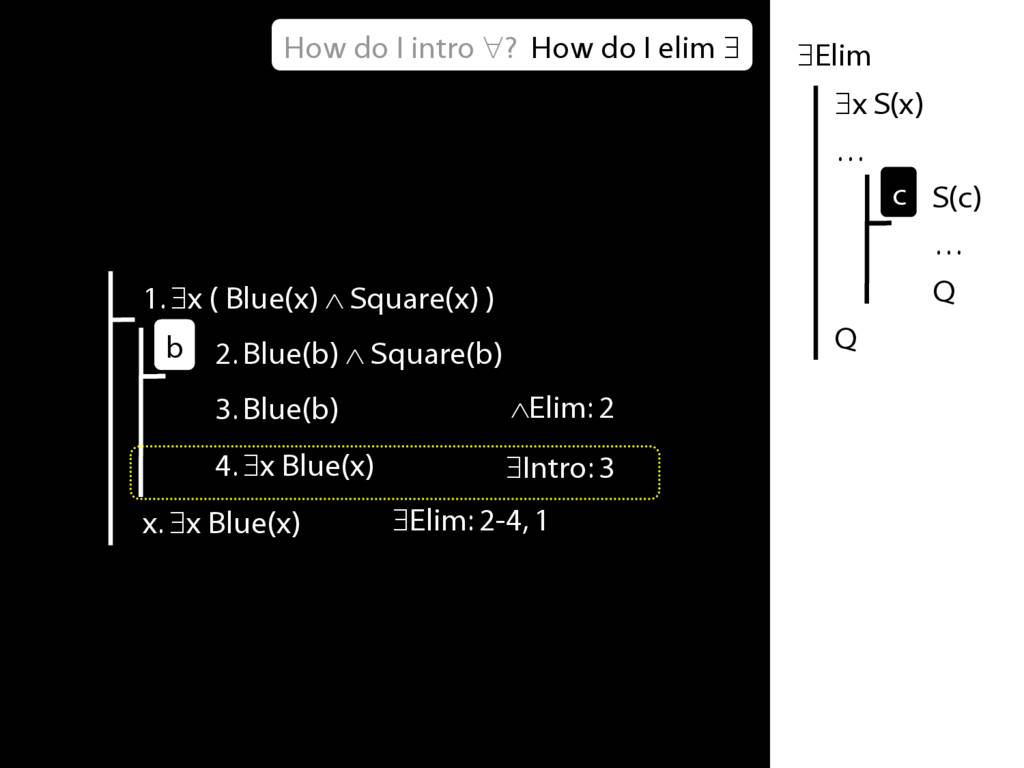

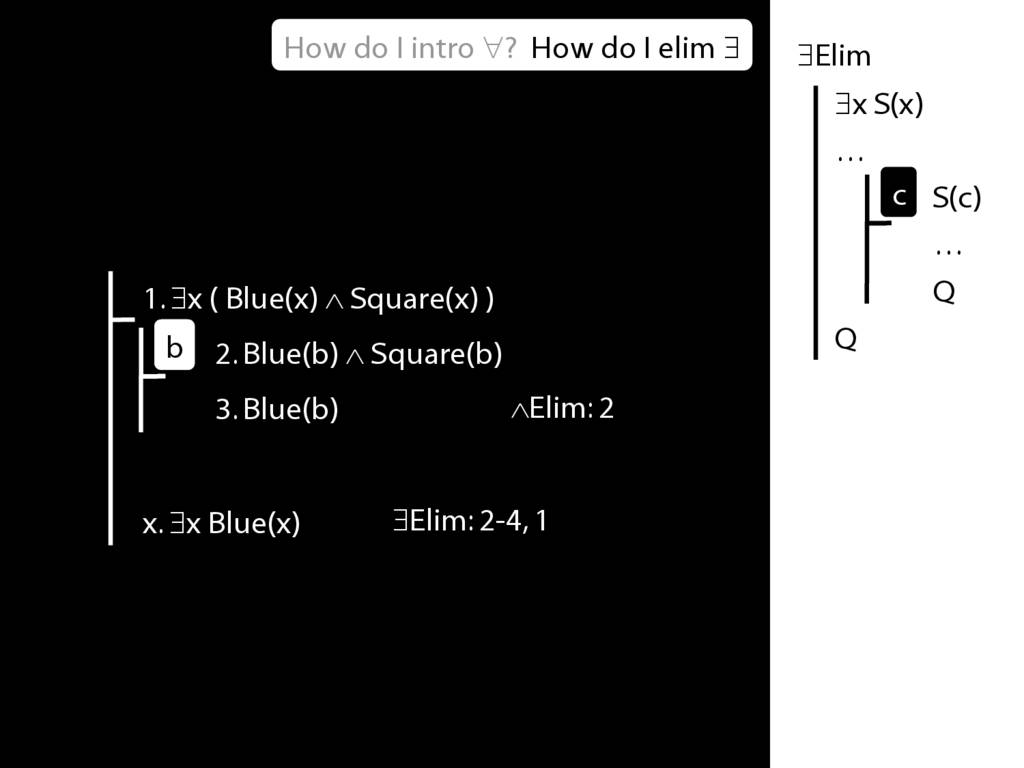

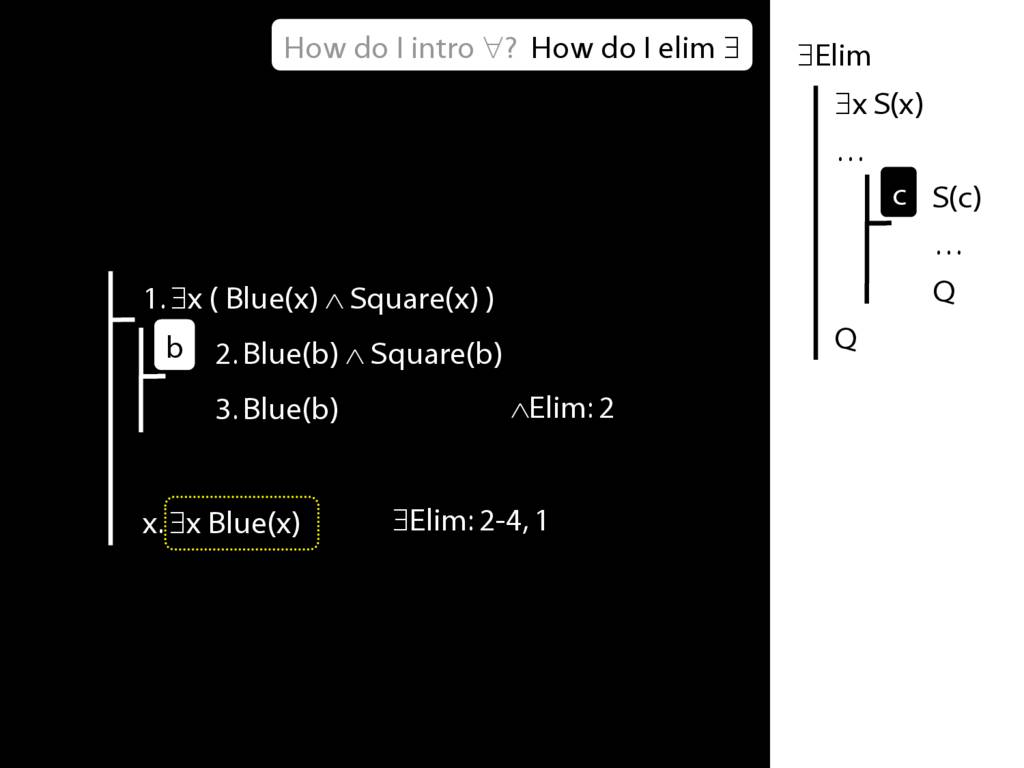

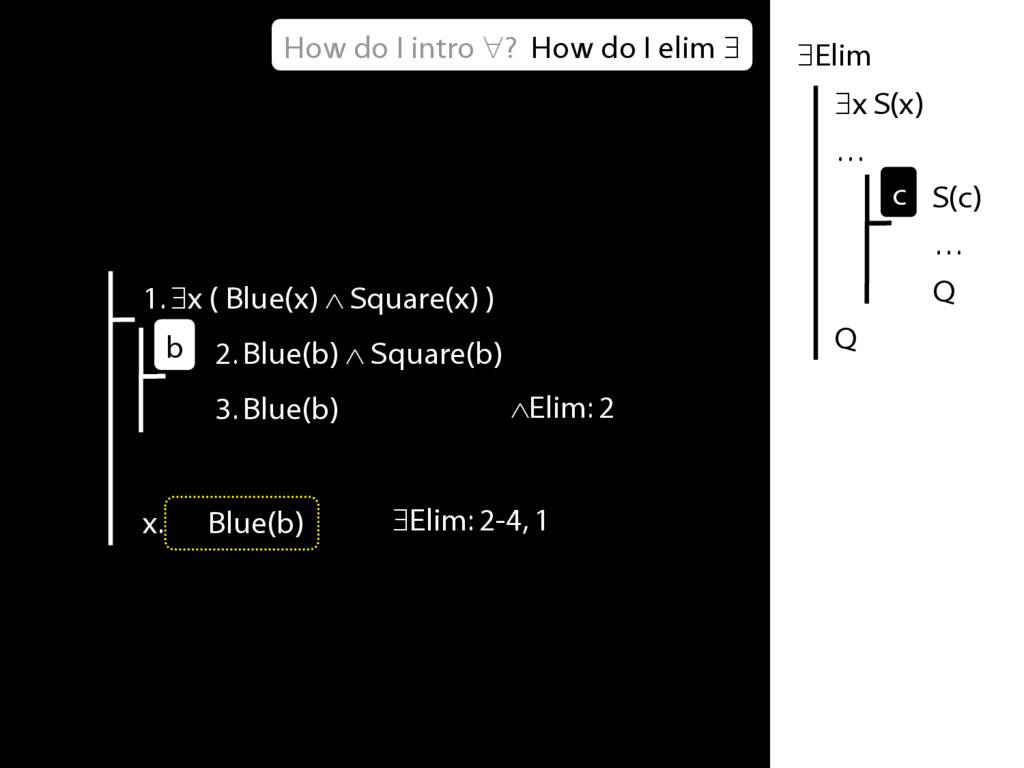

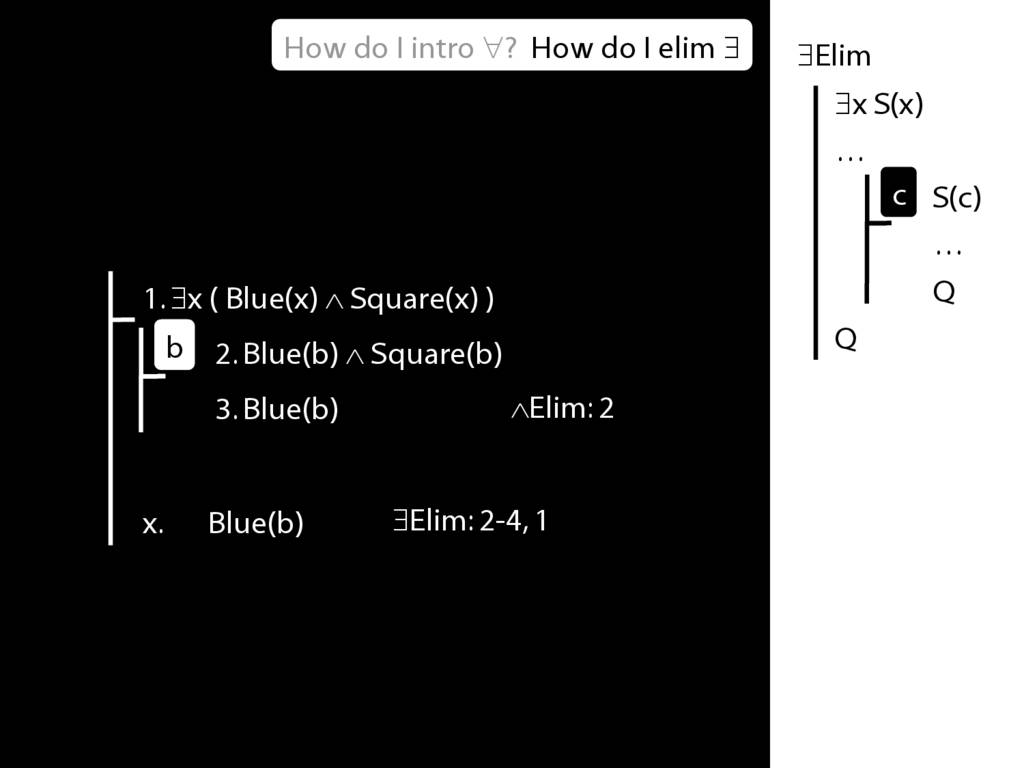

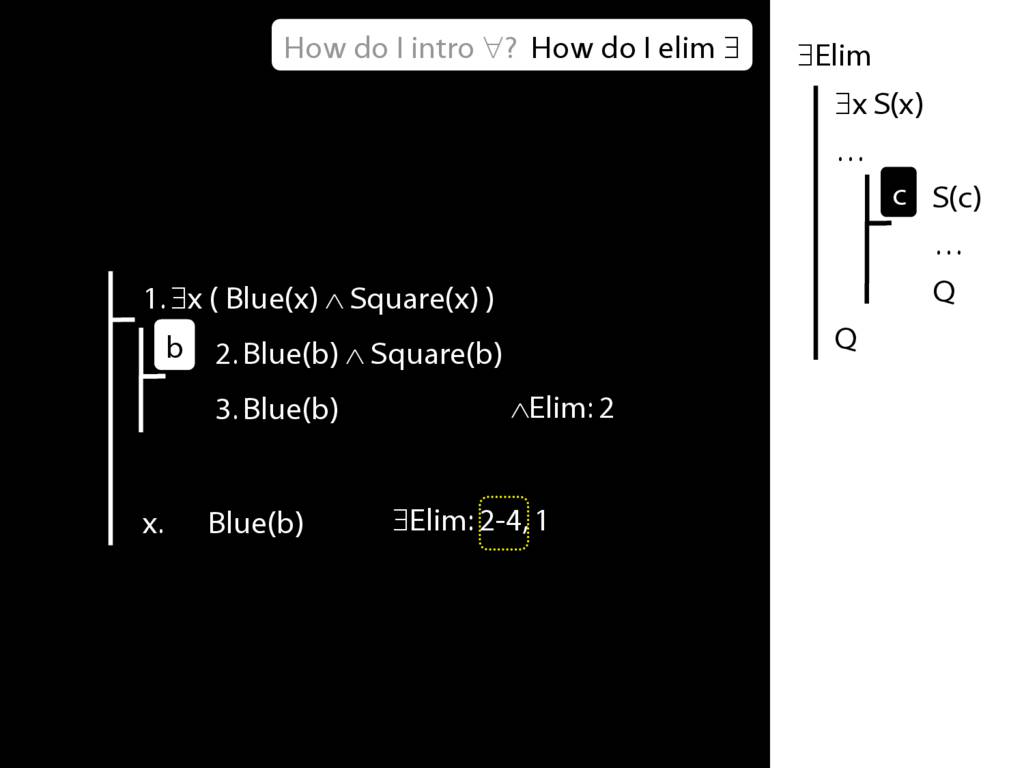

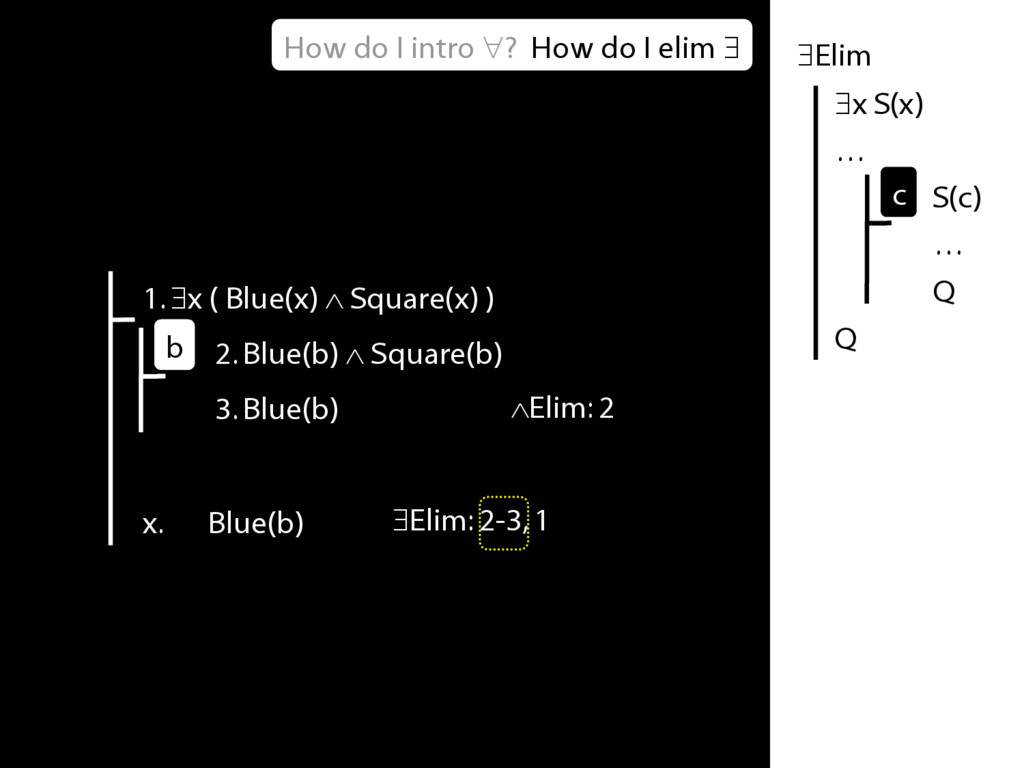

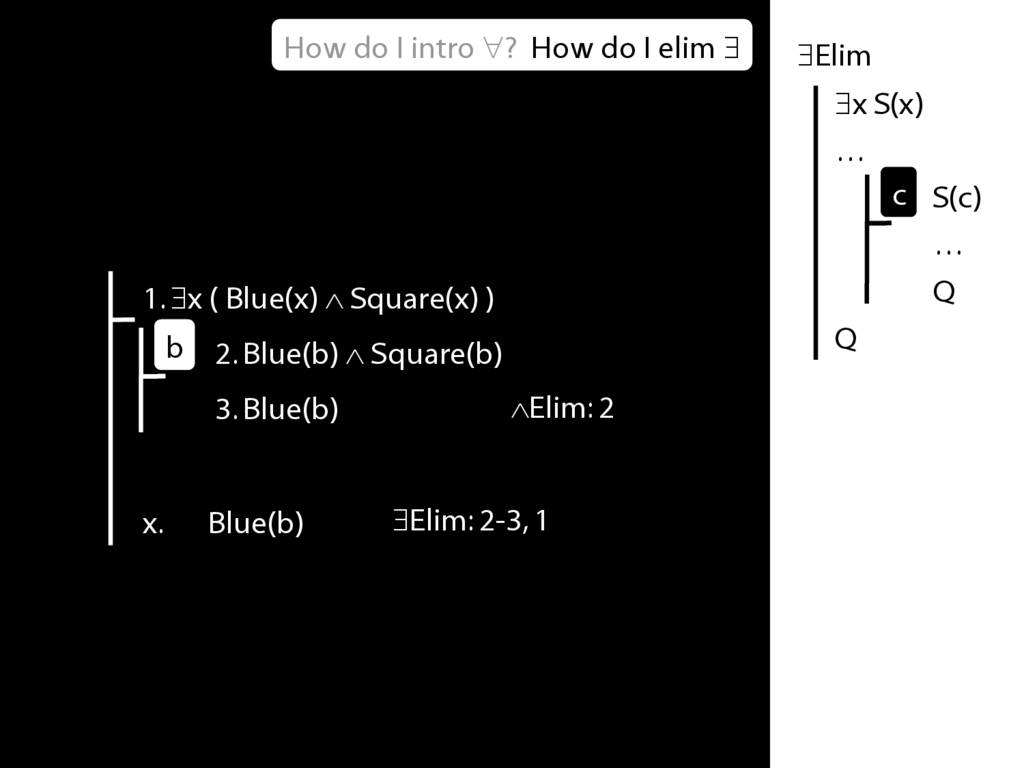

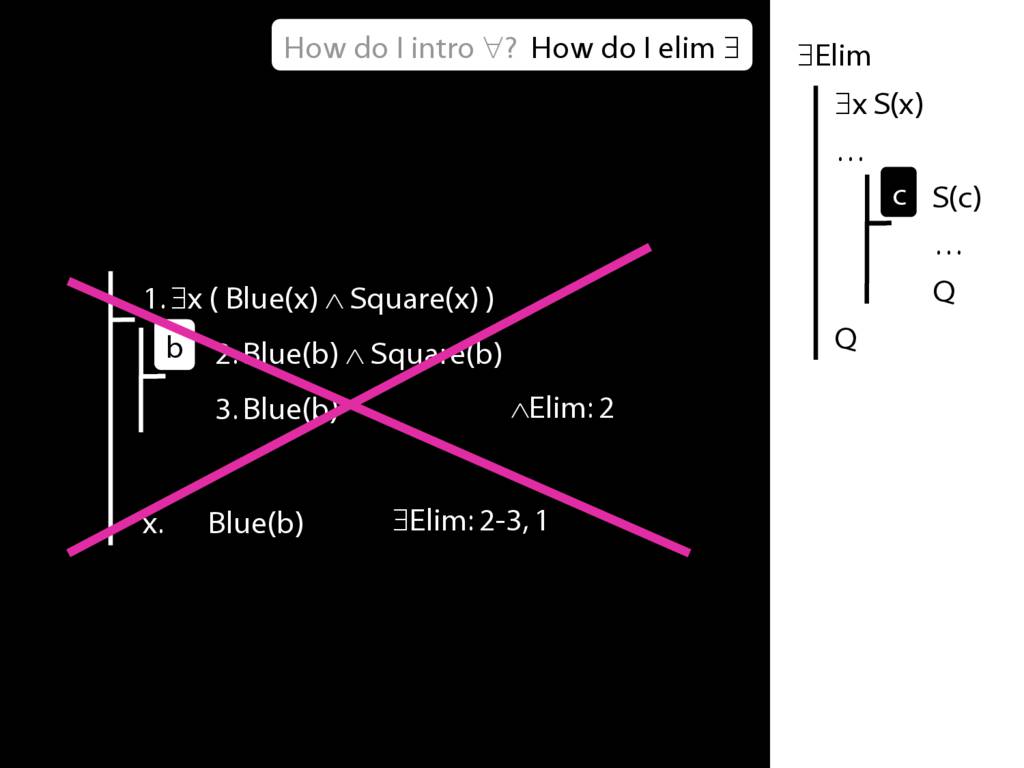

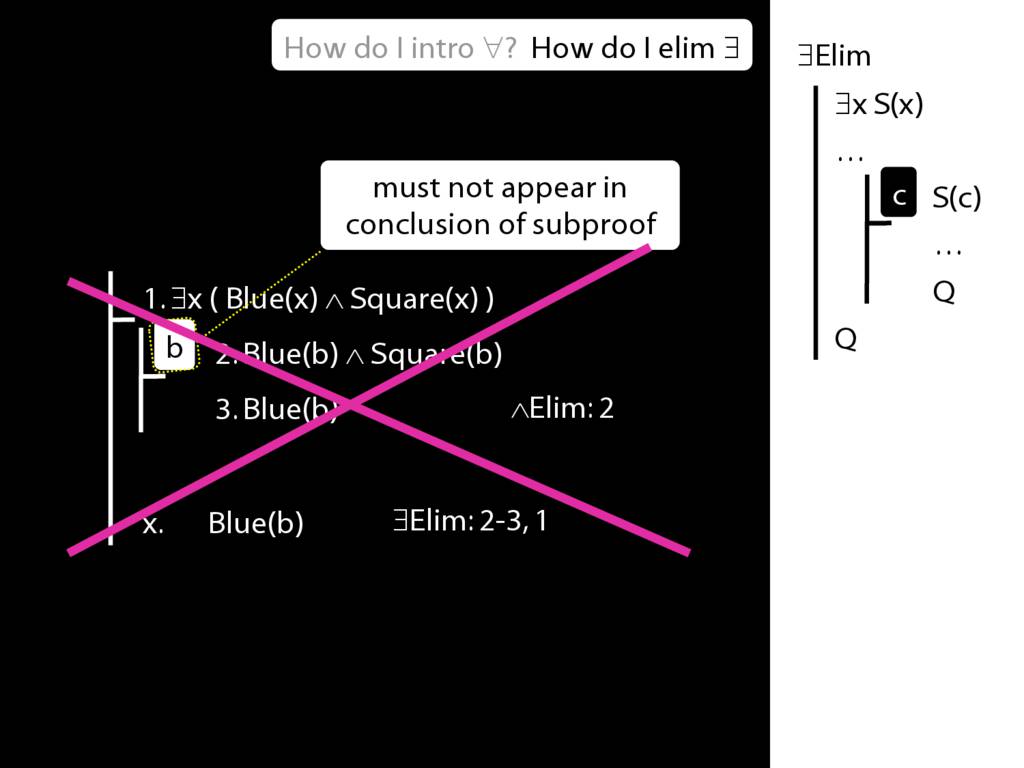

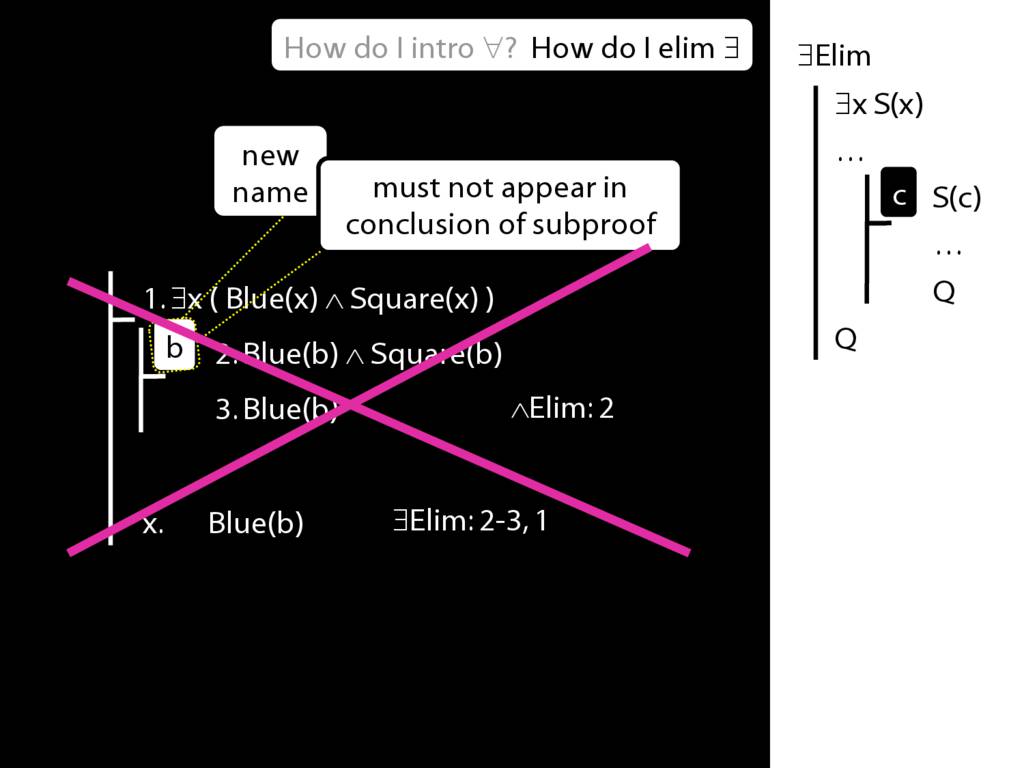

\section{∃Elim}

\emph{Reading:} §12.2, §13.2

\begin{minipage}{\columnwidth}

Note this restriction on the use of ∃Elim:

\end{minipage}

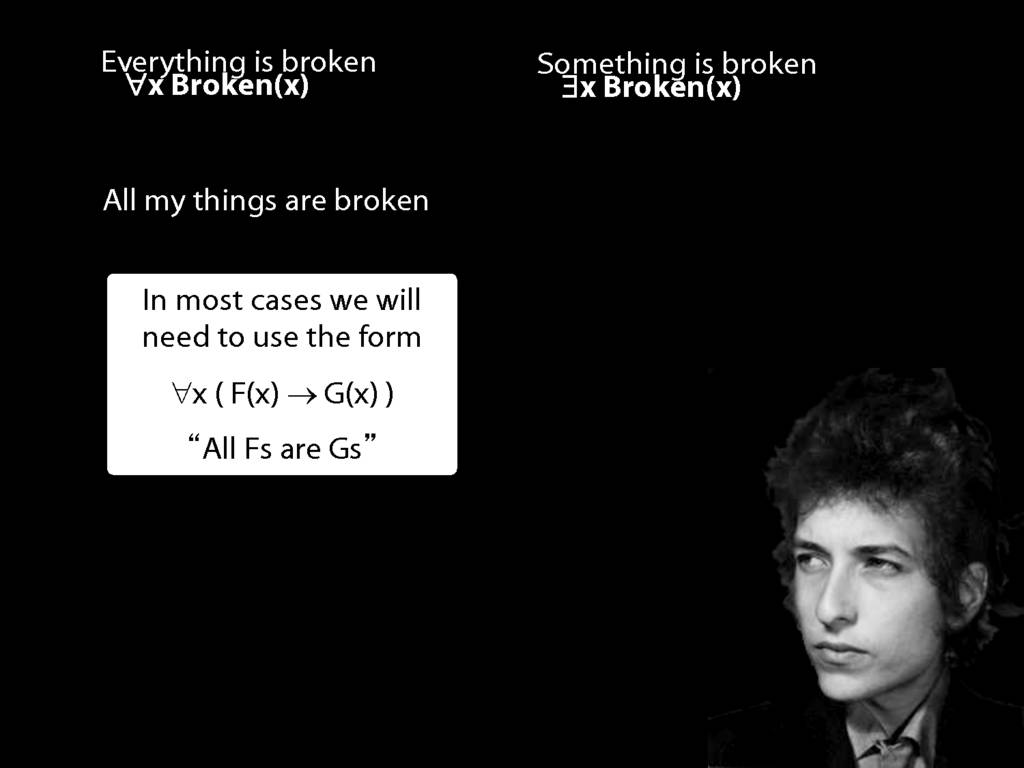

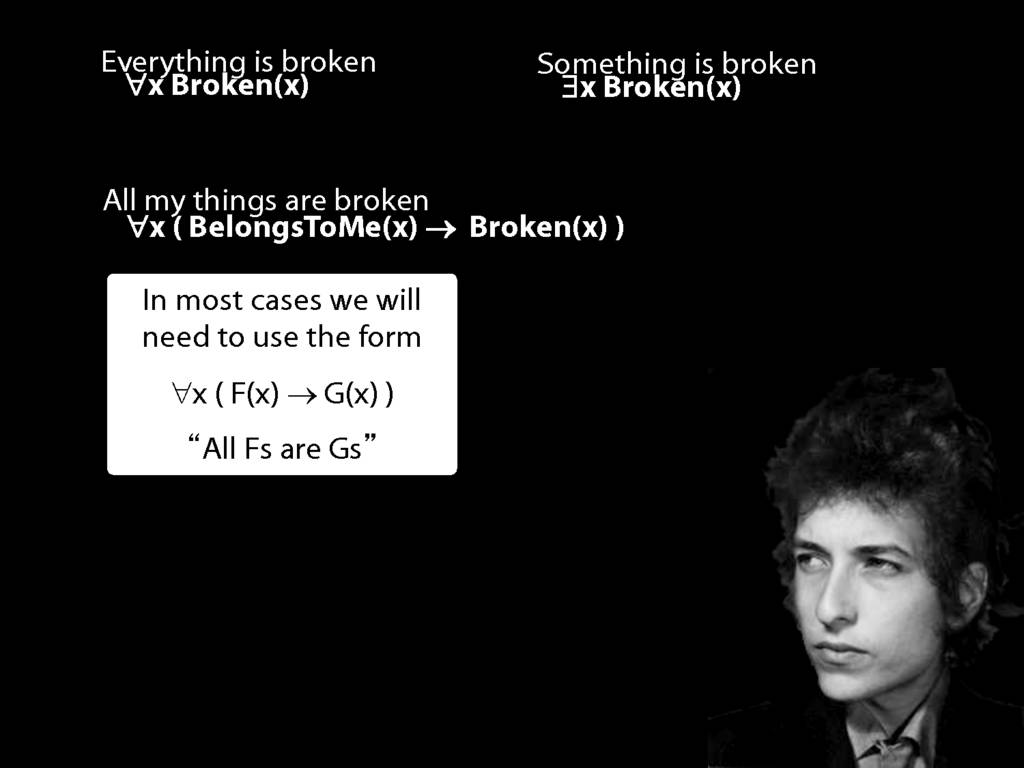

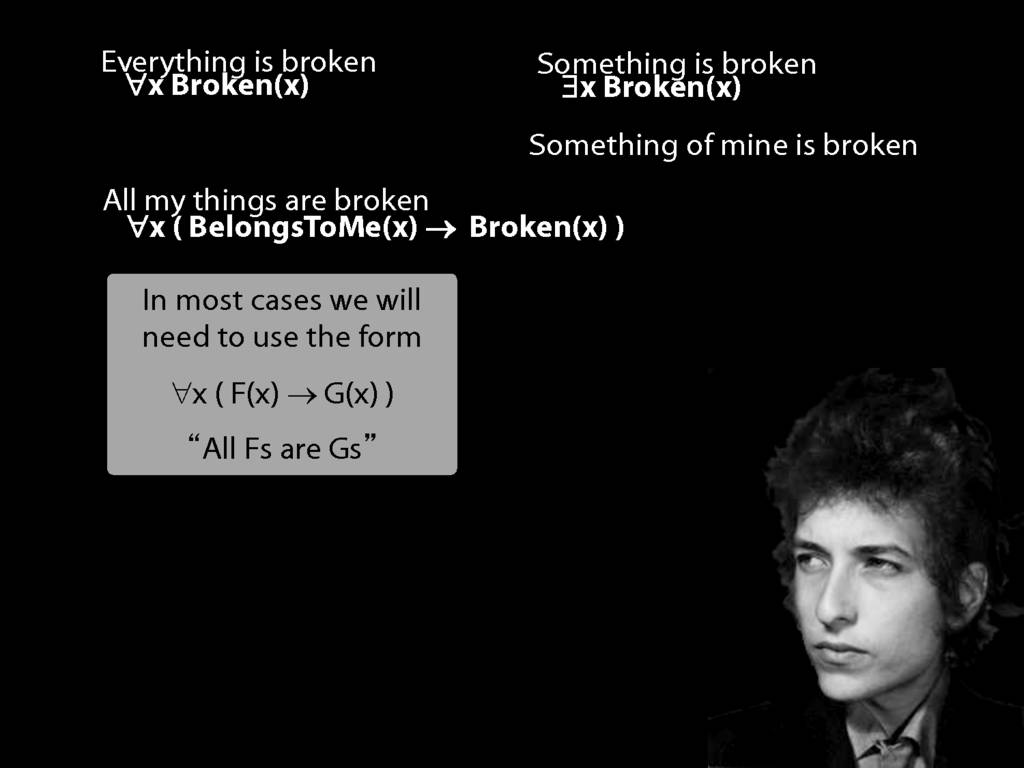

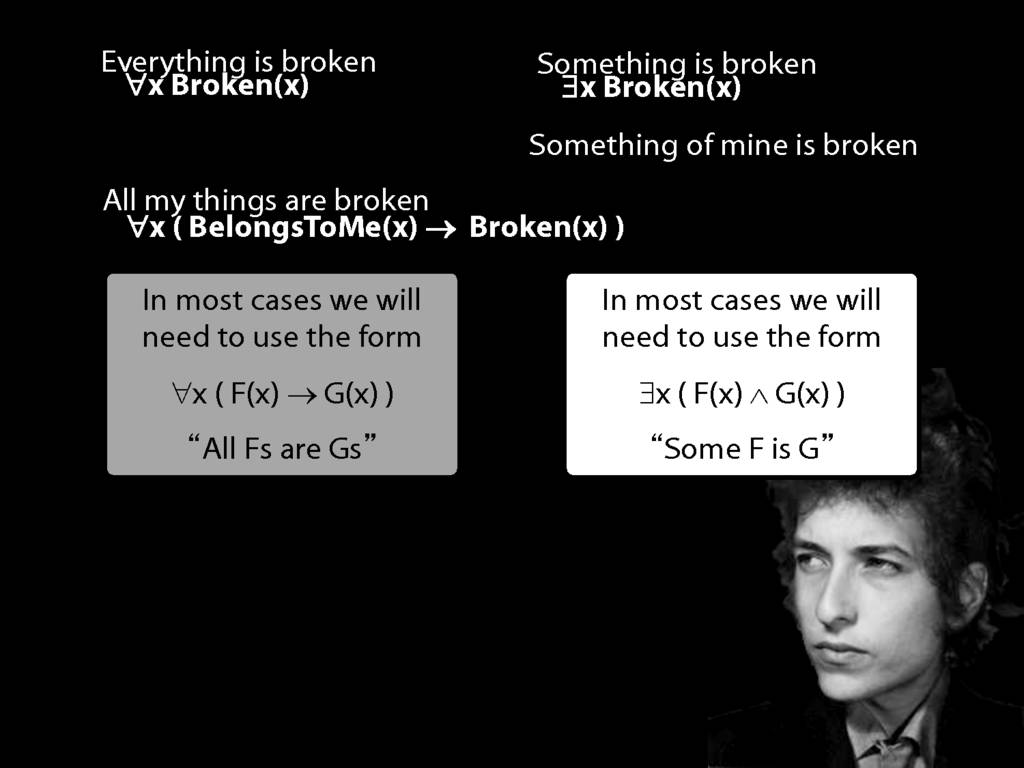

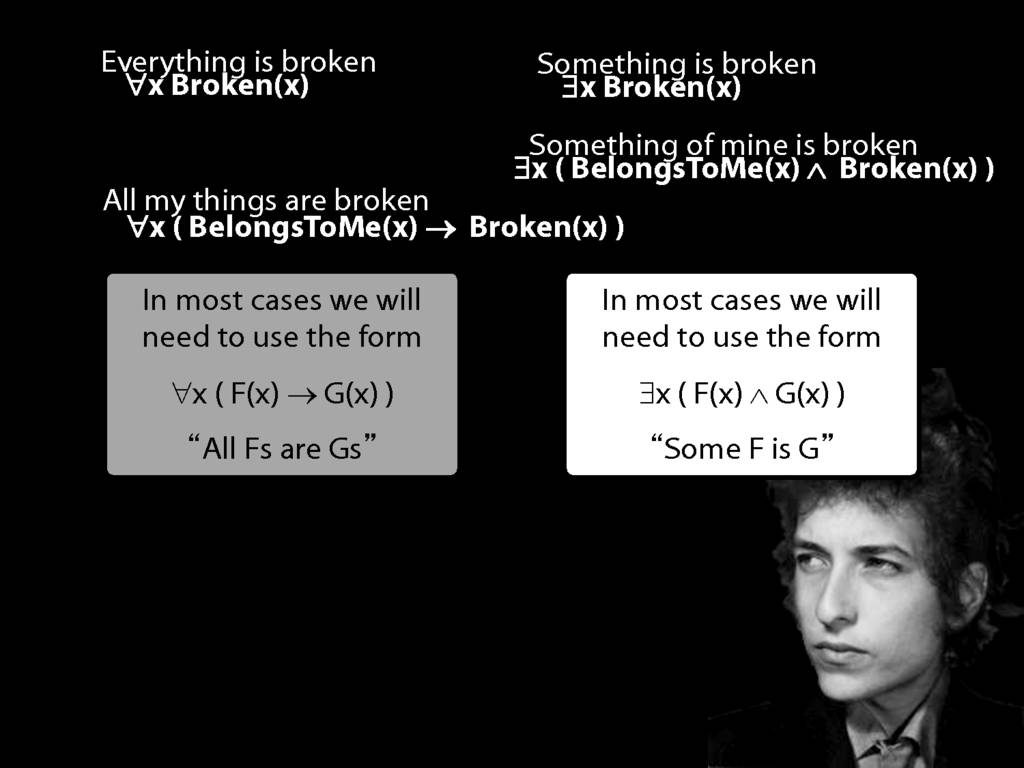

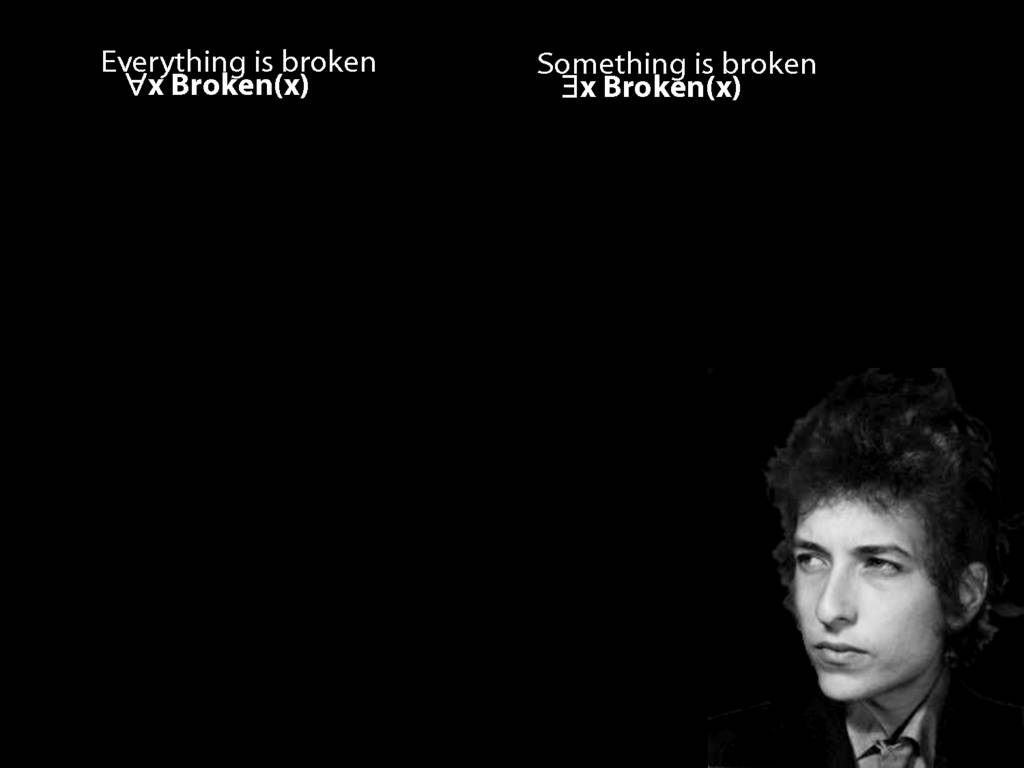

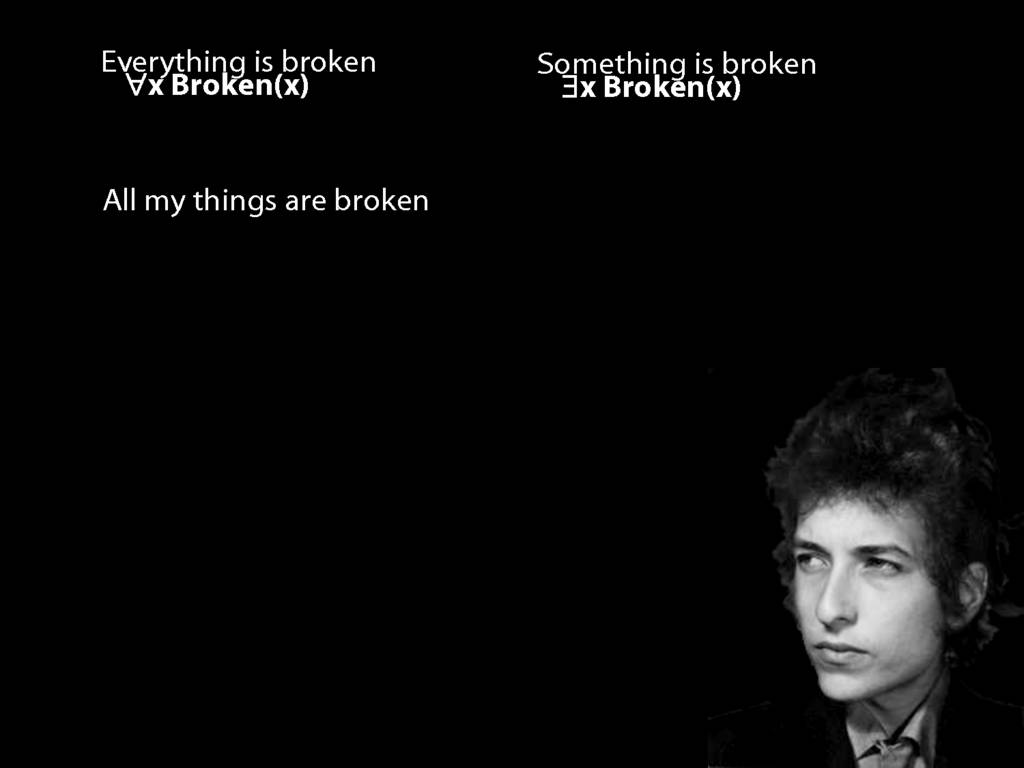

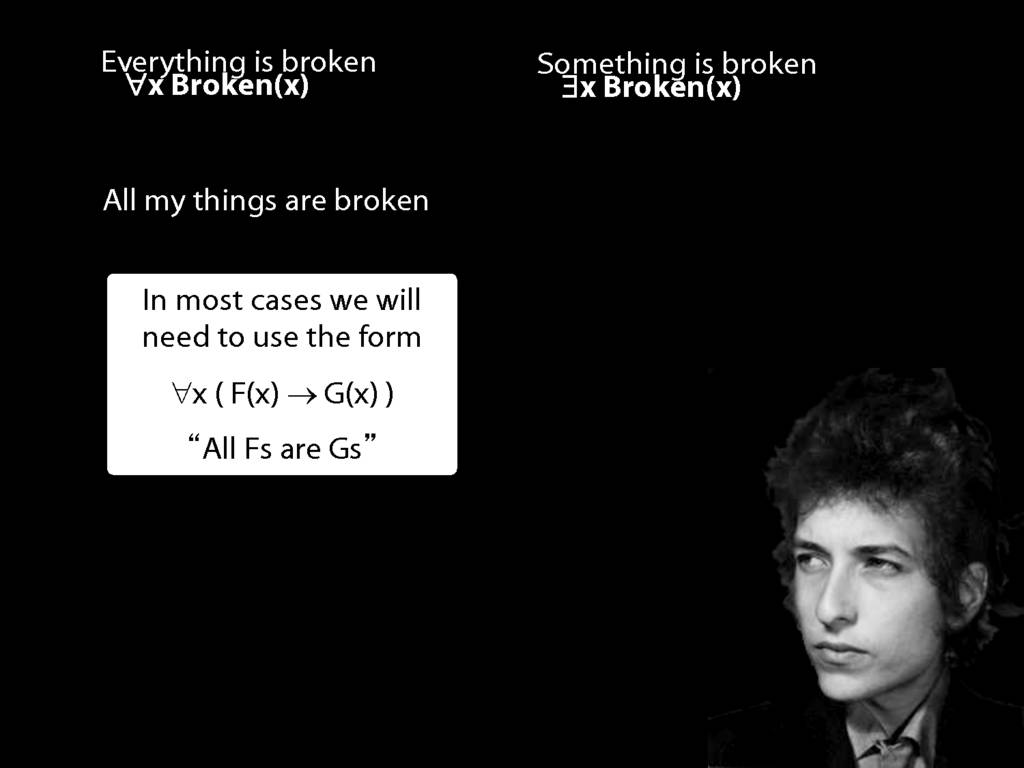

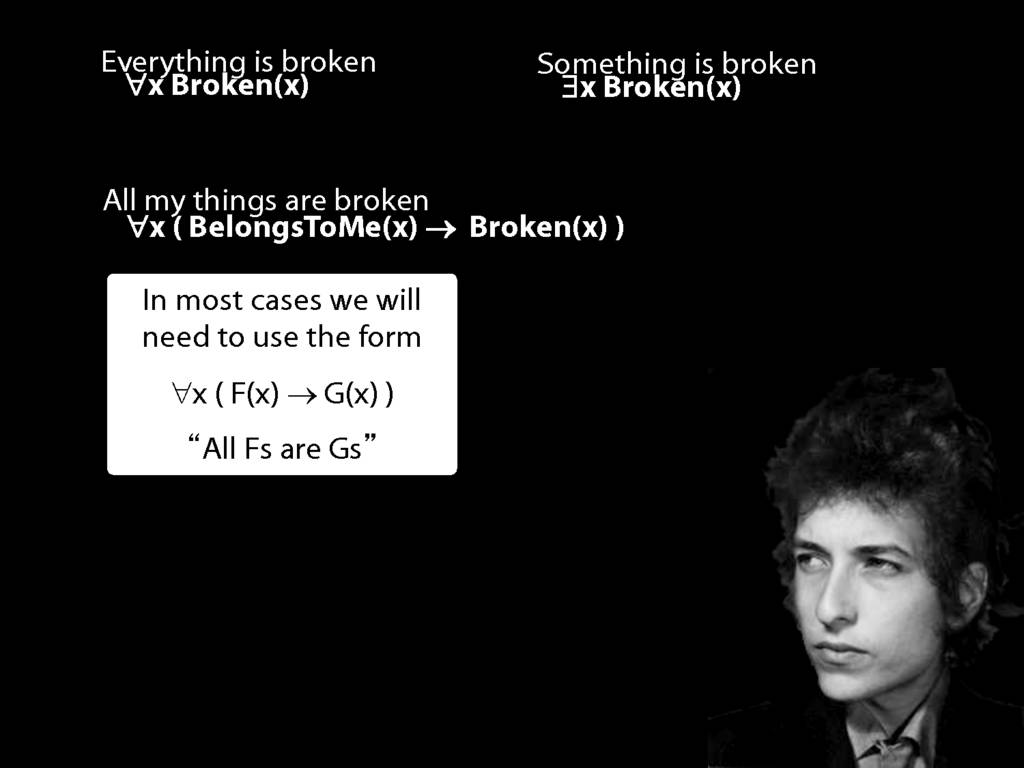

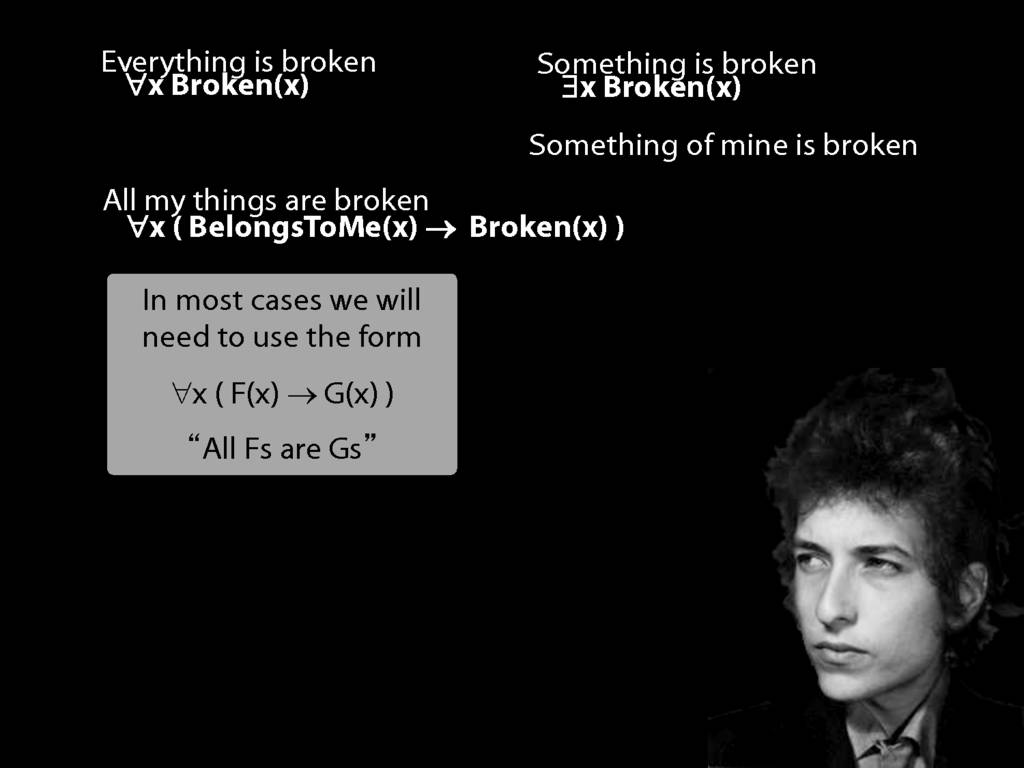

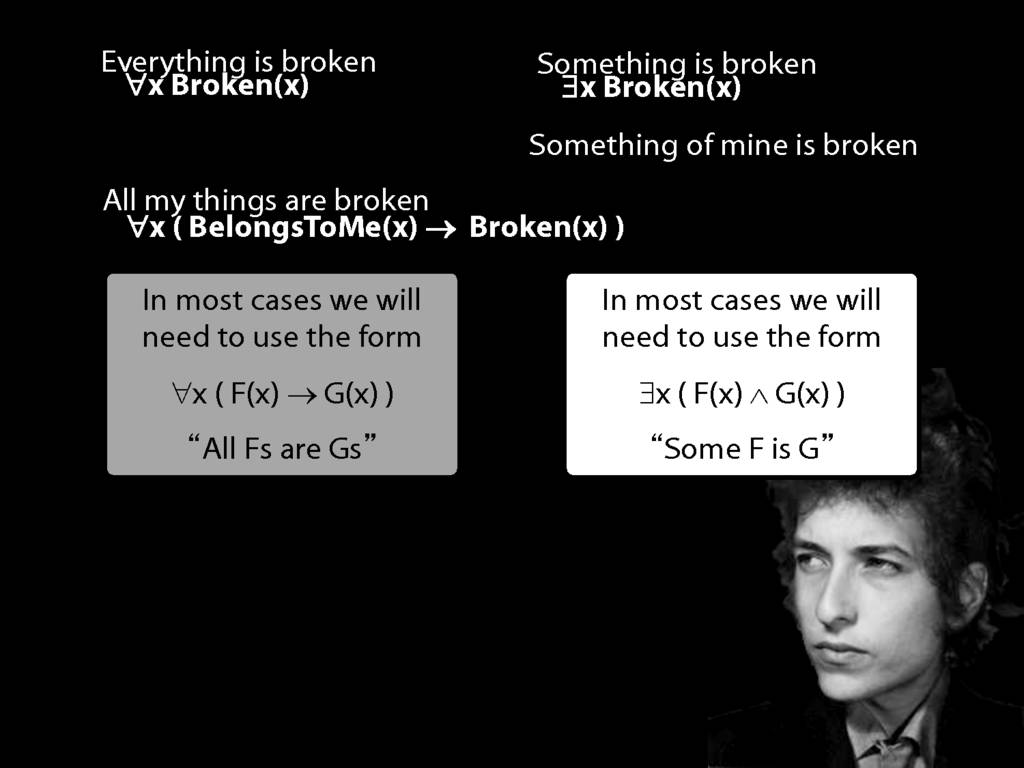

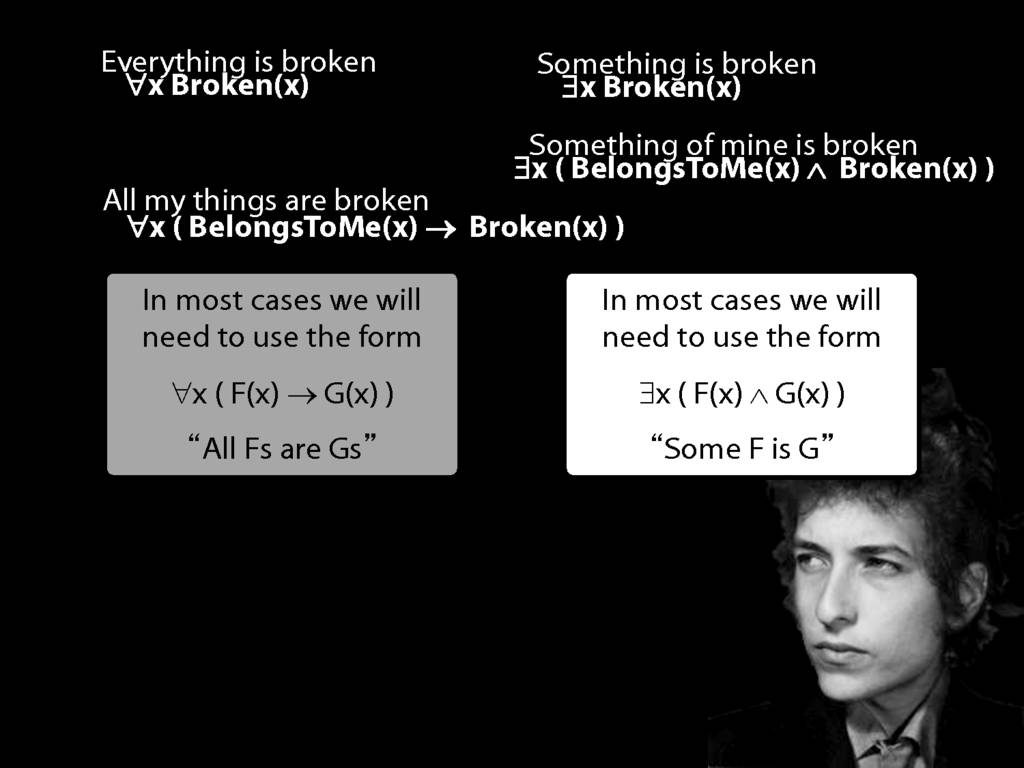

Translation with Quantifiers

\section{Translation with Quantifiers}

\emph{Reading:} §9.5, §9.6

\begin{minipage}{\columnwidth}

All discordians weep:

∀x( Dscrdn(x) → Wps(x) )

\end{minipage}

\begin{minipage}{\columnwidth}

All \textbf{quadrumanous} discordians weep:

∀x( ( \textbf{Quadr(x) ∧} Dscrdn(x) ) → Wps(x) )

\end{minipage}

\begin{minipage}{\columnwidth}

All quadrumanous discordians weep \textbf{and wail}:

∀x( ( Quadr(x) ∧ Dscrdn(x) ) → ( Wps(x) \textbf{ ∧ Wls(x)} ) )

\end{minipage}

\begin{minipage}{\columnwidth}

All quadrumanous discordians weep and wail \textbf{except Gillian Deleude}:

∀x( ( Quadr(x) ∧ Dscrdn(x) \textbf{∧ ¬(x=a)} ) → ( Wps(x) ∧ Wls(x) ) )

\end{minipage}

Some persuasive and useful arguments are not valid.

∃x(Persuasive(x) ∧ Useful(x) ∧ Argument(x) ∧ ¬Valid(x))

All discordians weep.

∀x( Dscrdn(x) → Wps(x) )

All quadrumanous discordians weep.

∀x( (Quadr(x)∧ Dscrdn(x) ) → Wps(x) )

All quadrumanous discordians weep and wail.

∀x( ( Quadr(x) ∧ Dscrdn(x) ) → ( Wps(x) ∧ Wls(x) ) )

All quadrumanous discordians weep and wail except Gillian Deleude.

∀x( ( Quadr(x) ∧ Dscrdn(x) ∧ ¬(x=a) ) → ( Wps(x) ∧ Wls(x) ) )

9.4–-9.5

9.8–-9.9

9.12-–9.13

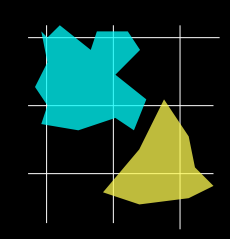

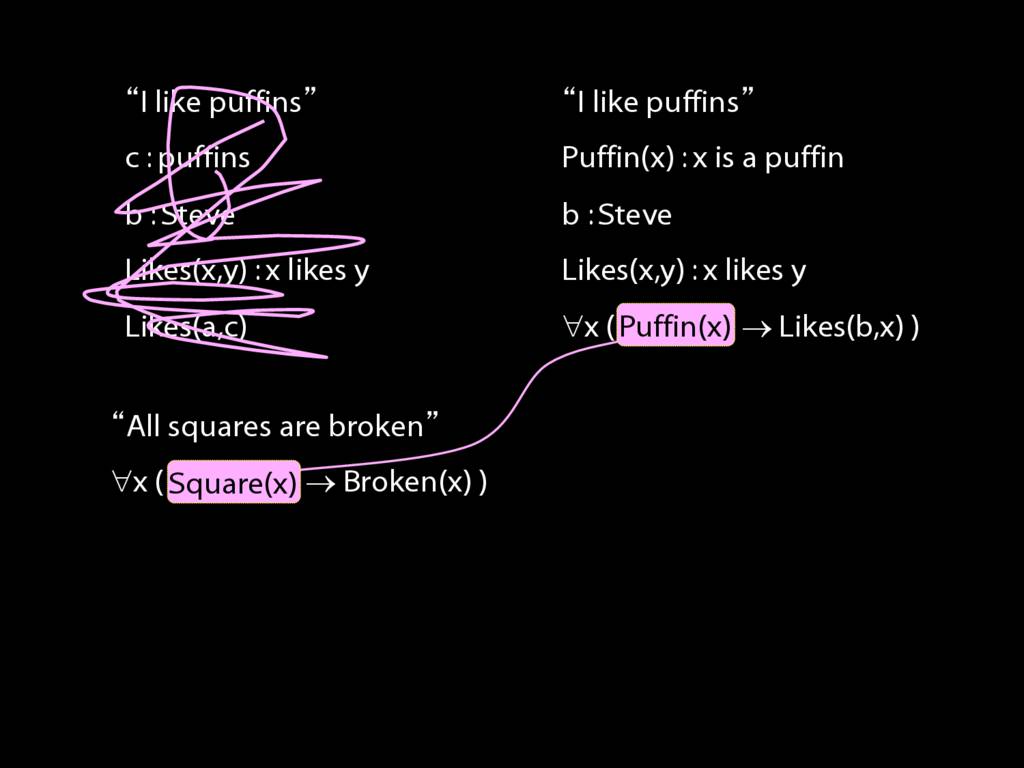

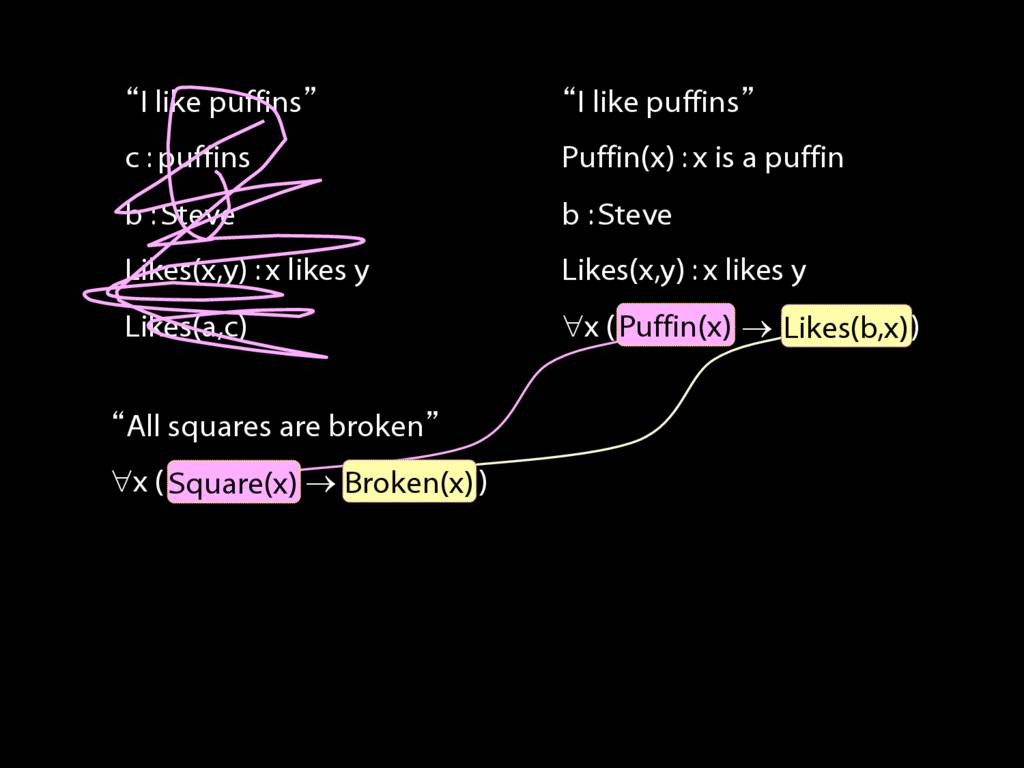

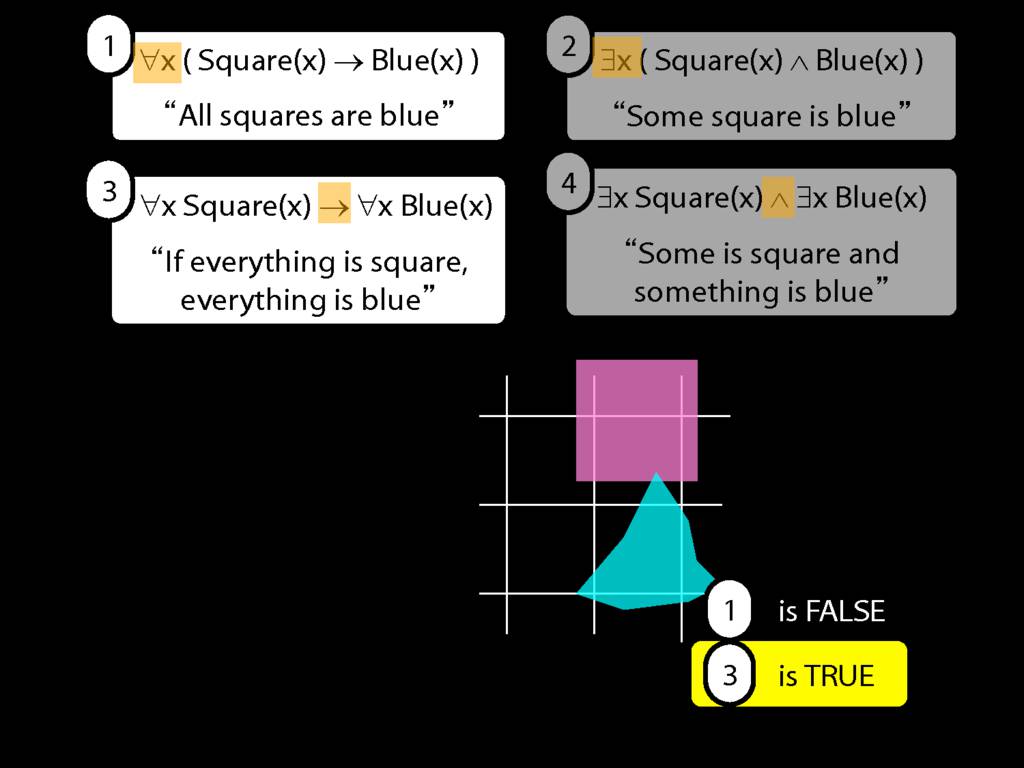

\section{Don't use ∃ with →}

\begin{minipage}{\columnwidth}

Is true ∃x(Square(x) → Broken(x)) in this world?

\end{minipage}

∃x(Square(x) → Broken(x))

\hspace{3mm} ⫤⊨

∃x(¬Square(x) ∨ Broken(x))

\hspace{3mm} ⫤⊨

∃x(¬Square(x)) ∨ ∃x(Broken(x))

1.

∀x(Square(x) ∧ Broken(x))

2.

∀x(Square(x) → Broken(x))

⫤⊨

3.∀x(¬Square(x) ∨ Broken(x))

4.∃x(Square(x) ∧ Broken(x))

5.∃x(Square(x) → Broken(x))

⫤⊨

6.∃x(¬Square(x) ∨ Broken(x))

⫤⊨

7.∃x(¬Square(x)) ∨ ∃x(Broken(x))

nb

∀x(¬Square(x) ∨ Broken(x)) ⊭ ∀x(¬Square(x)) ∨ ∀x(Broken(x))

1. is false

2. is true

4. is false

5. is ???

9.10

9.15--9.17

*9.18--9

9.10

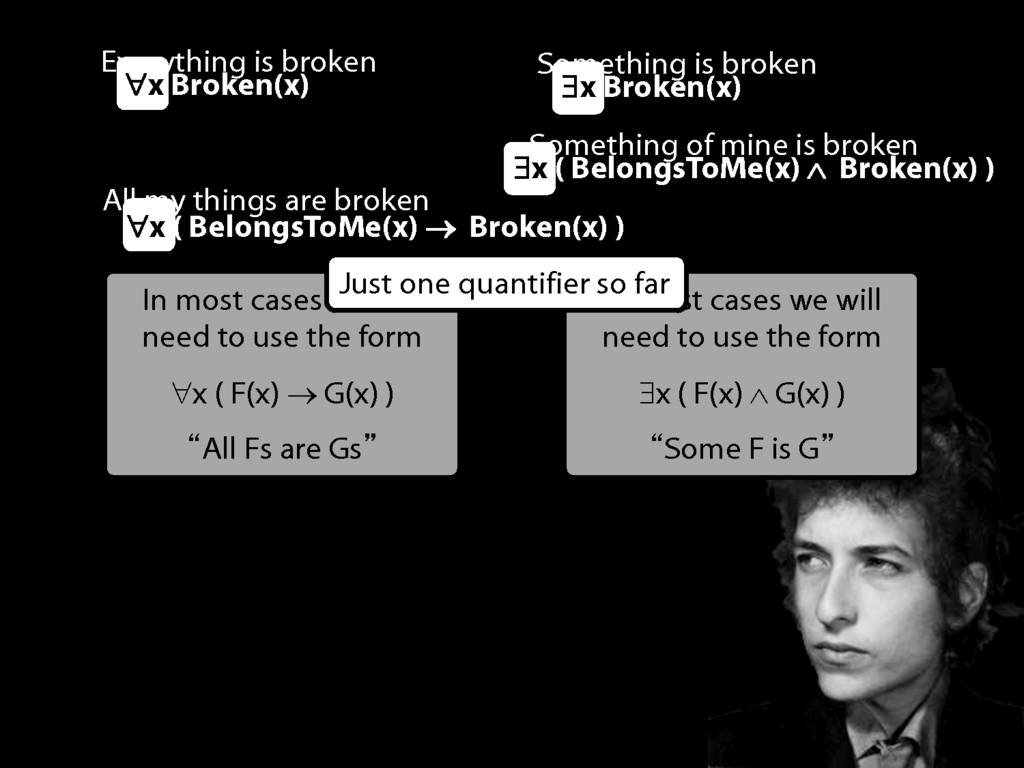

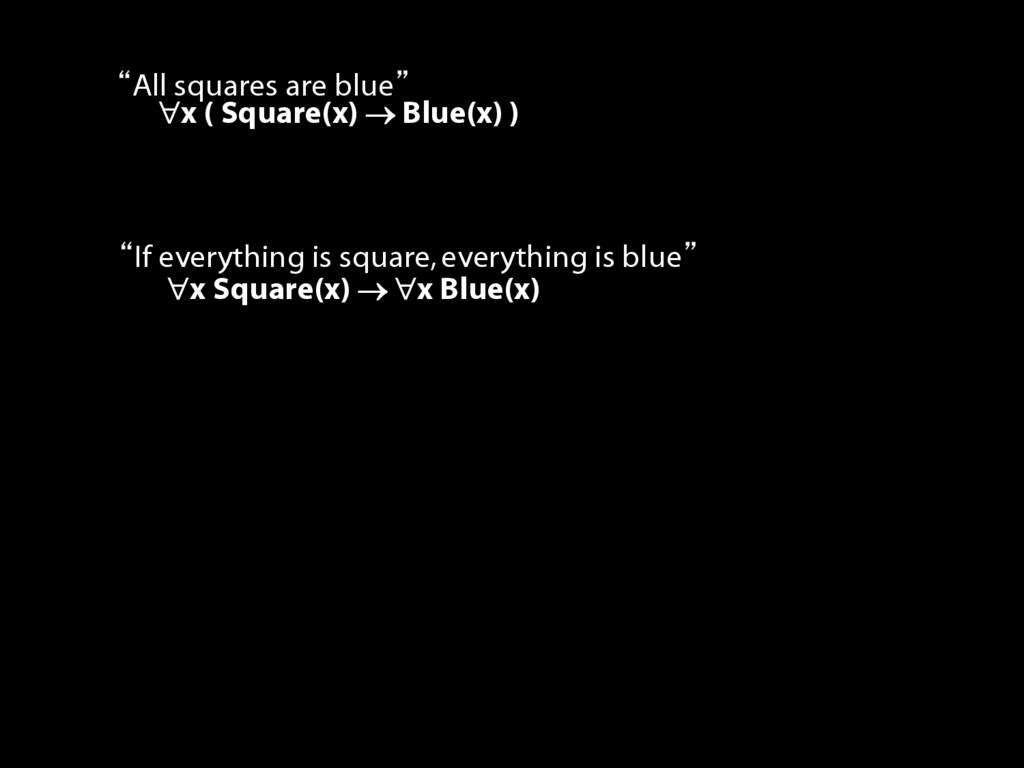

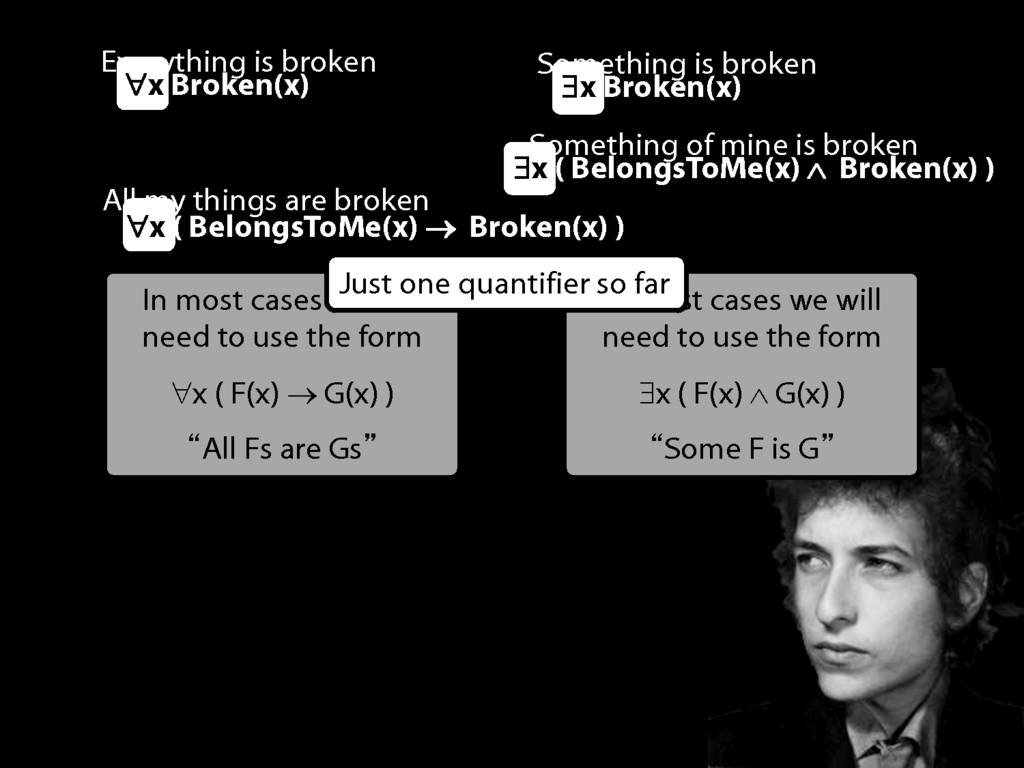

Watch Out, Here Come Multiple Quantifiers

\section{Watch Out, Here Come Multiple Quantifiers}

\emph{Reading:} §11.1

Let me give you a brief history of our engagement with quantification.

We started with the simplest case.

This sort of thing is great if you're a poet, but not much use otherwise.

Even Aristotle knew way, way back before the internet that it was necessary, in order to do useful logic,

to have more sophisticated forms of expression in our formal language.

And this was great, I mean people were really happy with this for like, 2000 years or more,

I think that, logically speaking, they were easily entertained---quite unlike you and me, of course.

They were content to say some squares are blue or whatever,

and you know they spent quite a long time sorting out the logic of sentences like these.

But the thing about these sentences is that they involve just one quantifier whereas, if you think about it, ...

... many ordinary senetnces are not like this.

Every time I go to the dentist someone dies.

Many ordinary sentences, like this line from Phoebe in friends, involve not just one quantifier ...

... but two. One of the big advances in modern logic is that it provides us with tools powerful enough to deal with sentences involving arbitrary combinations of quantifiers.

This is one main topic for the next lectures (another is proofs involving quantifiers).

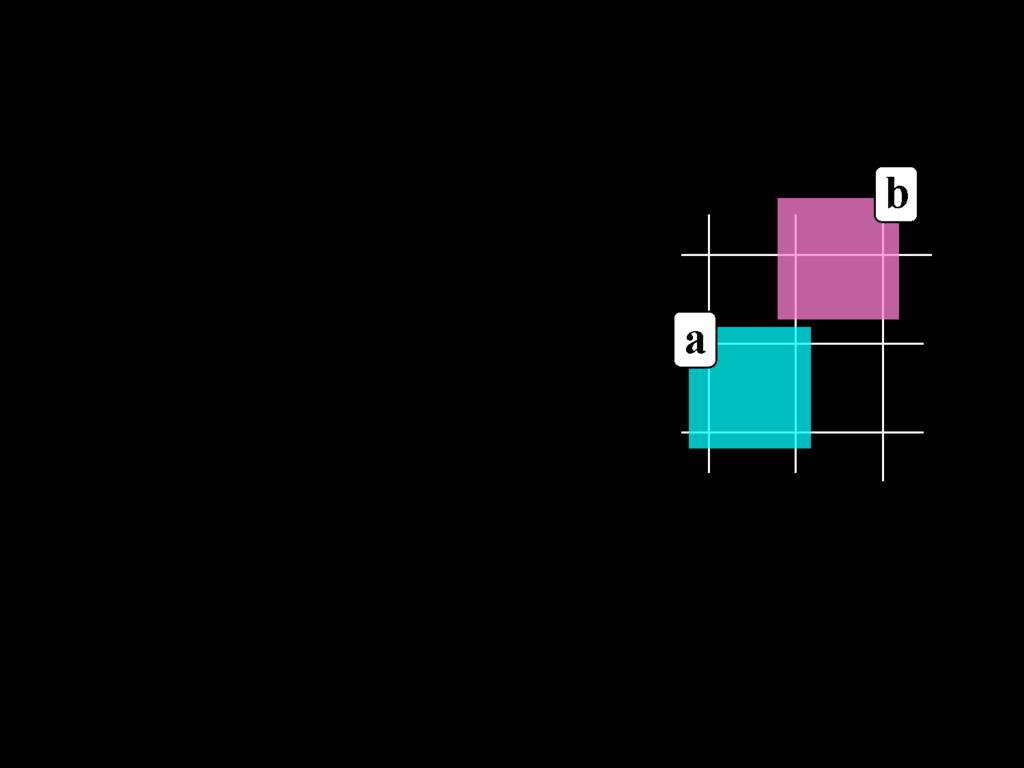

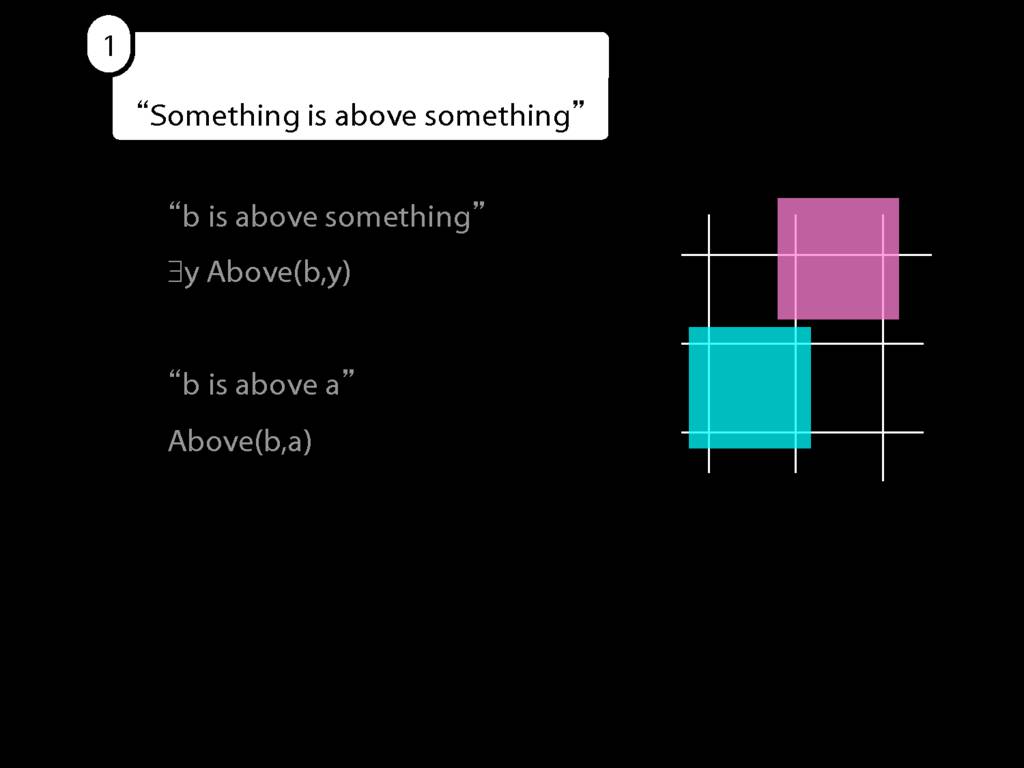

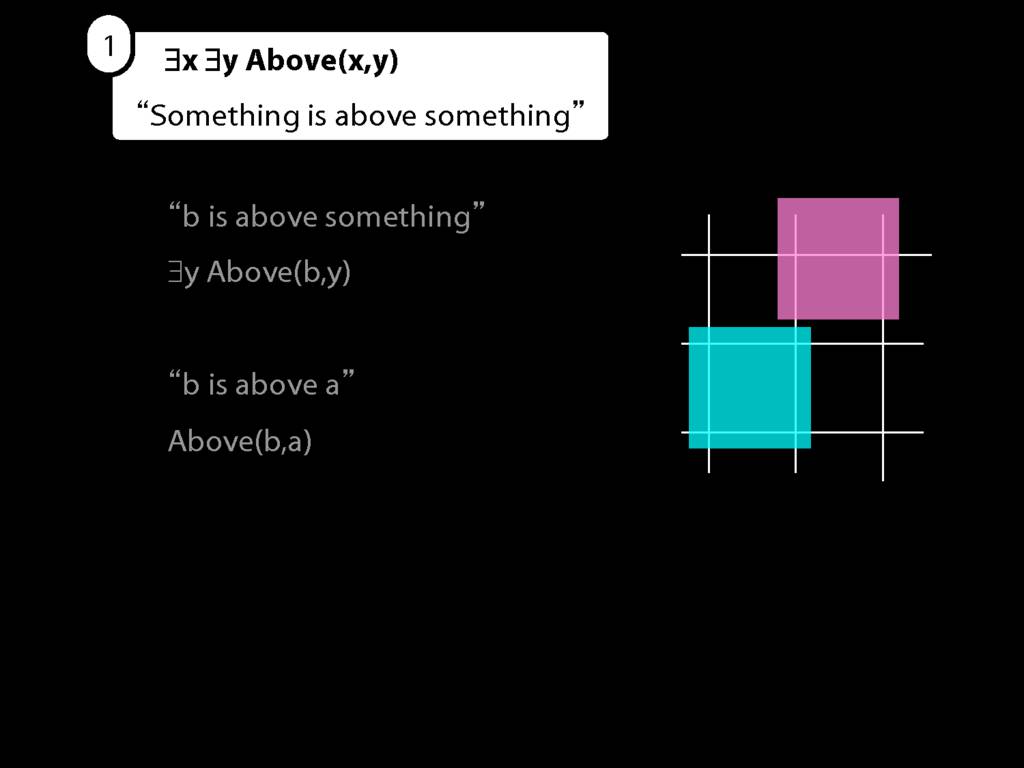

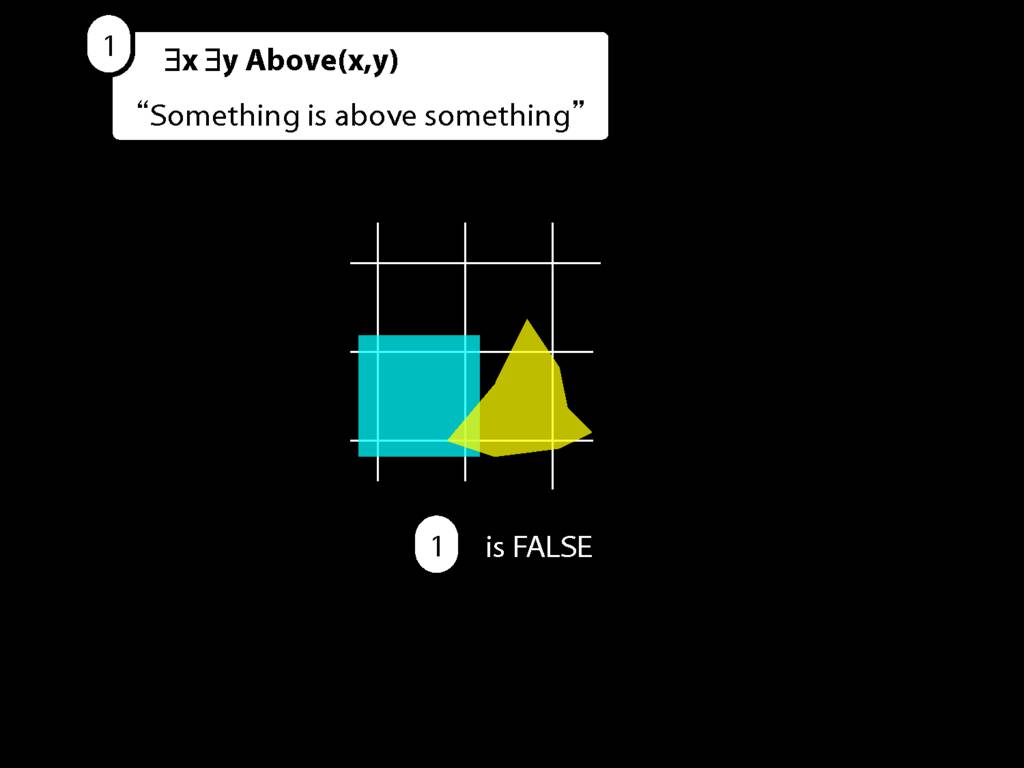

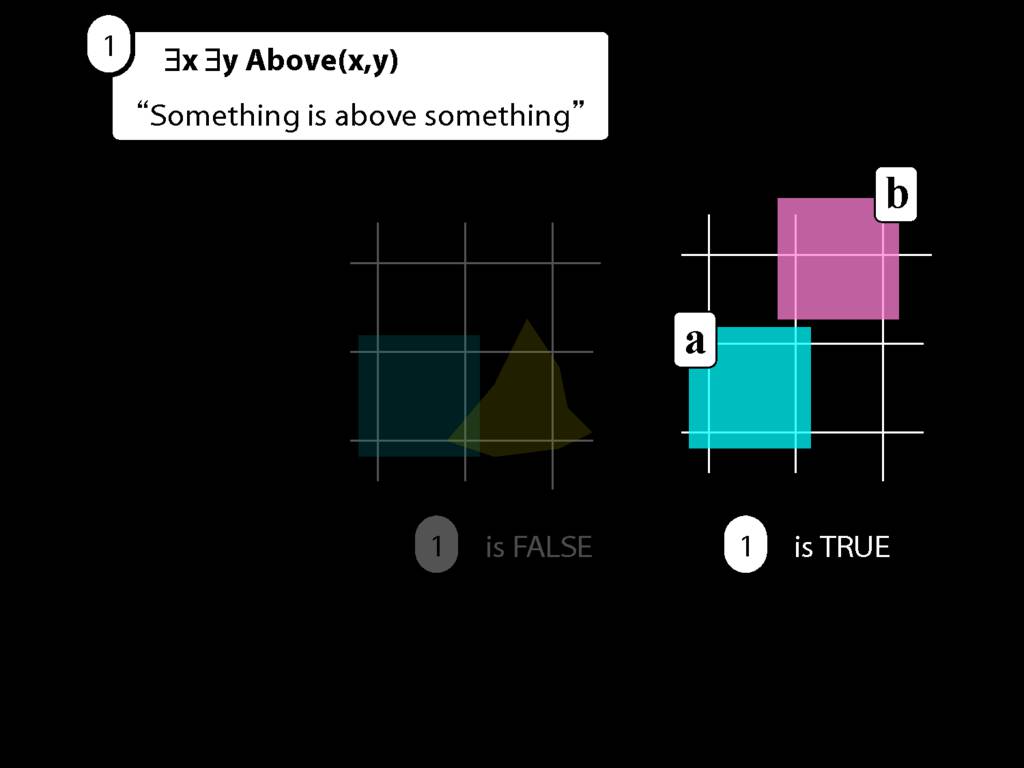

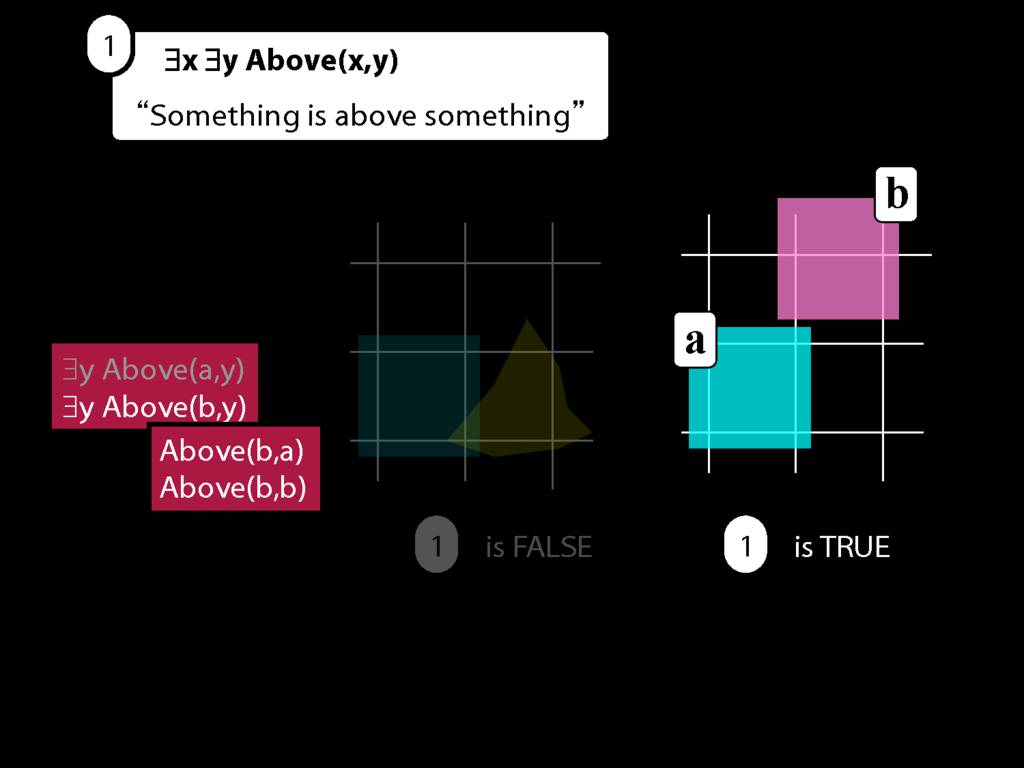

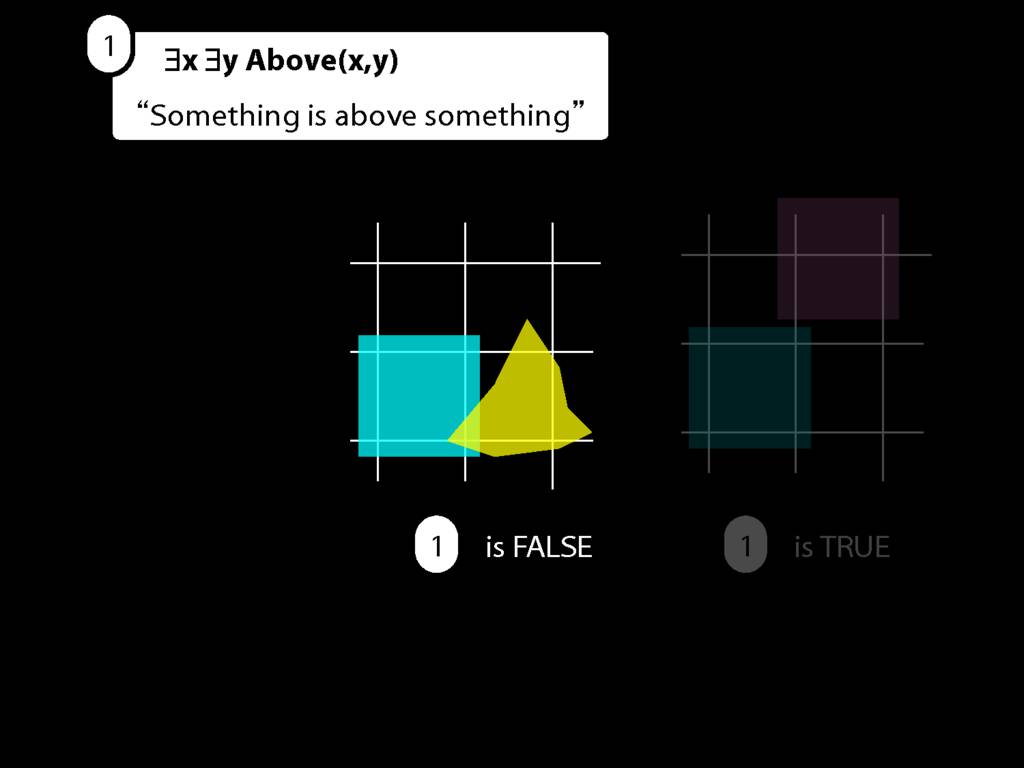

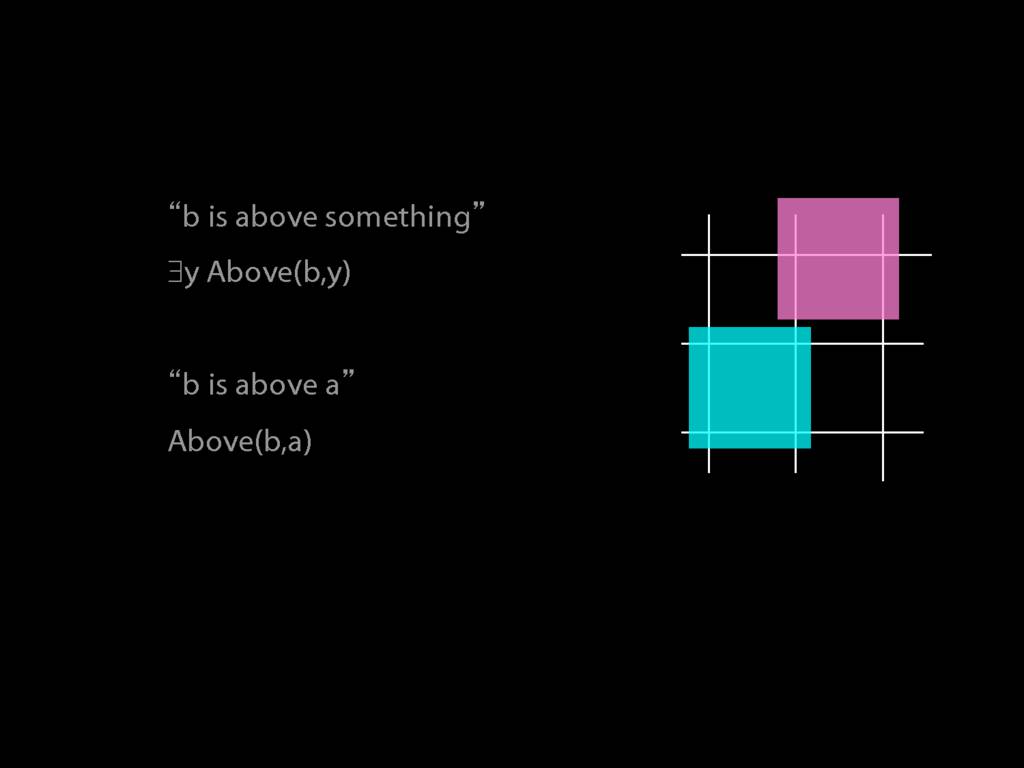

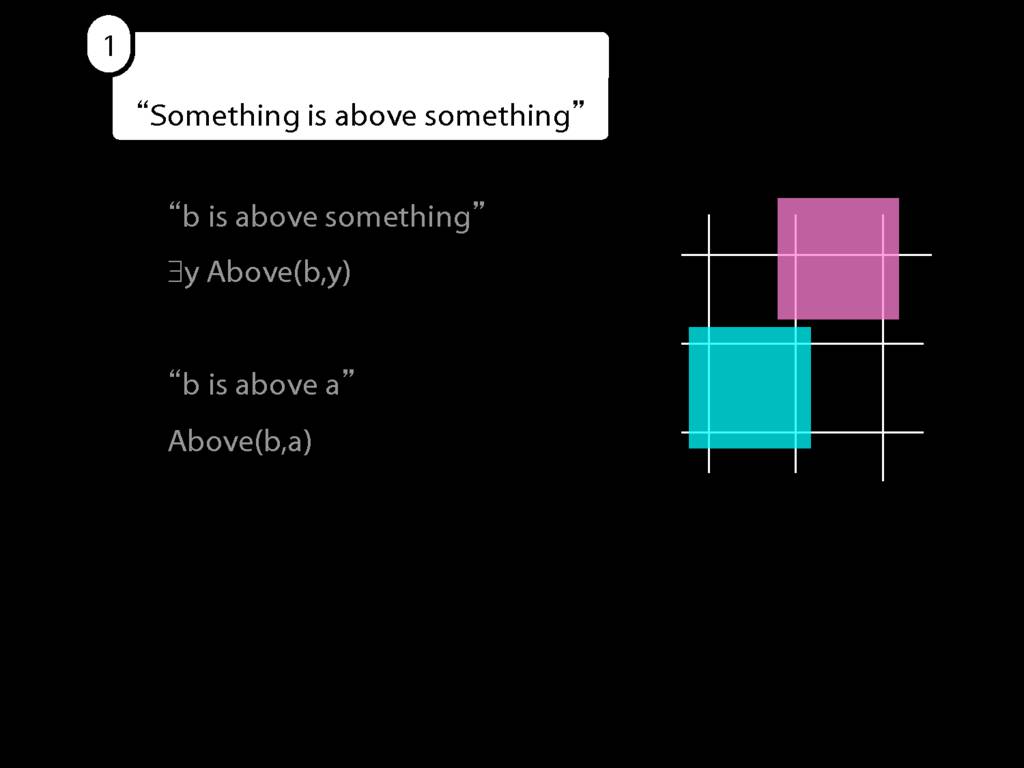

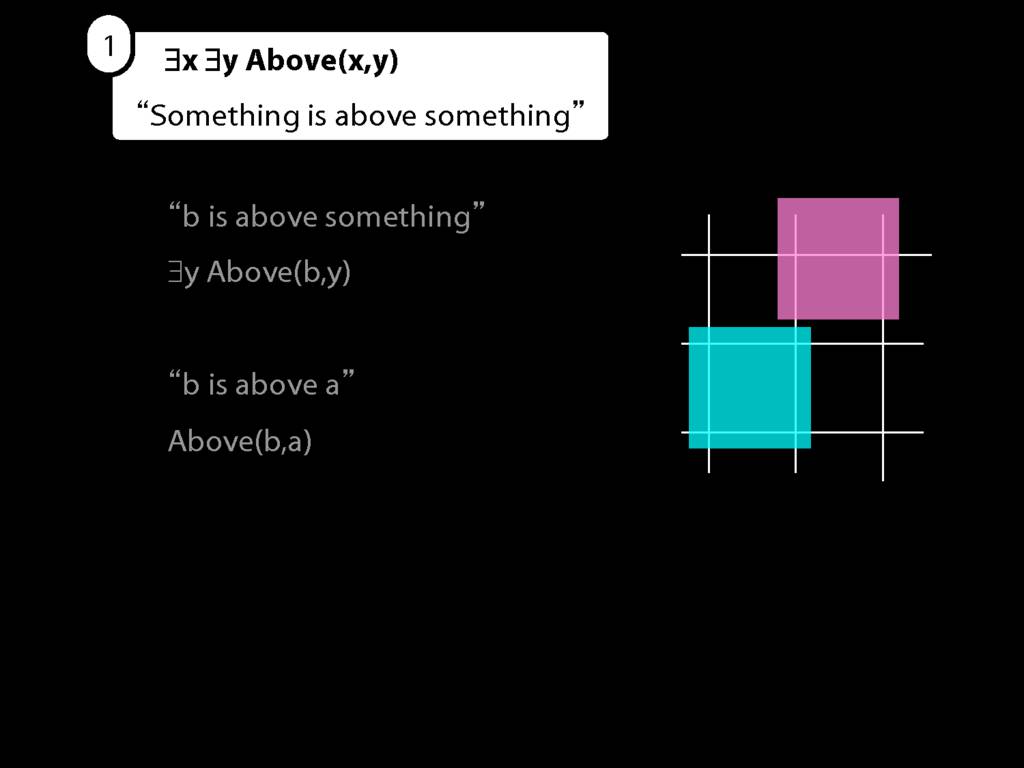

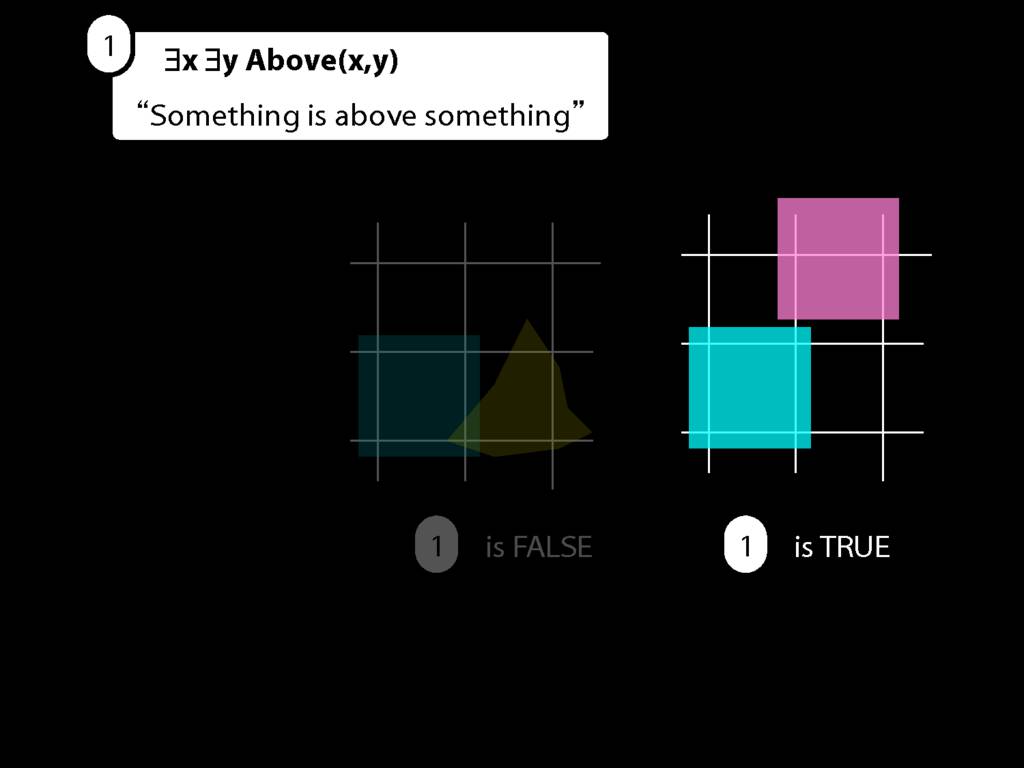

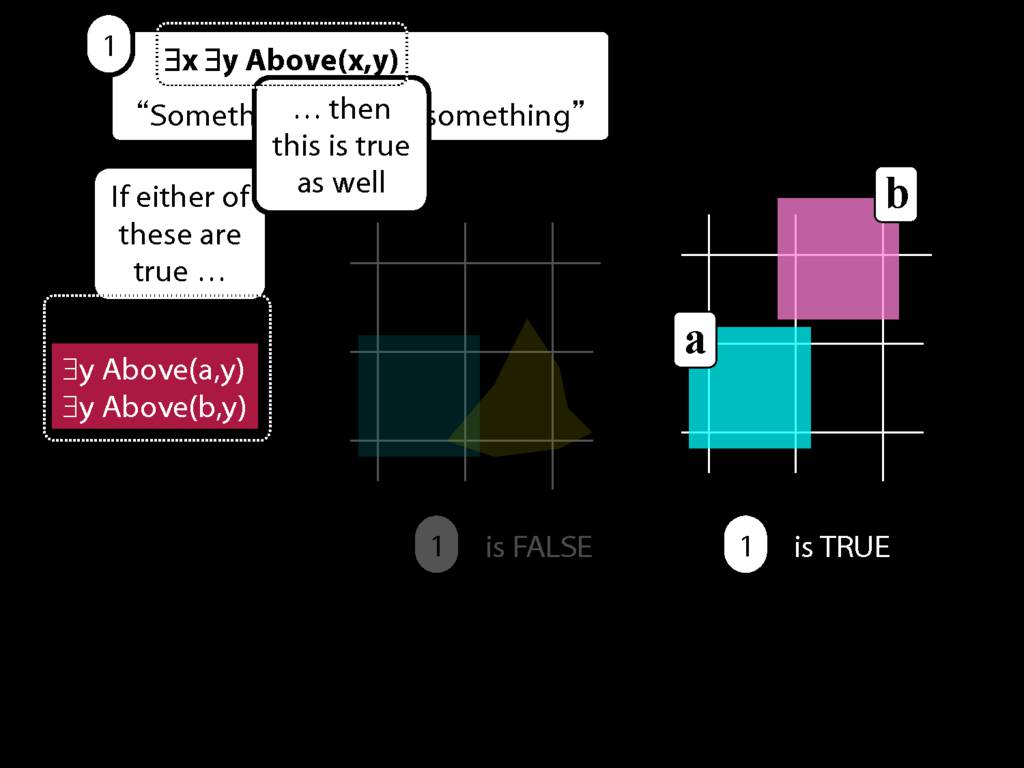

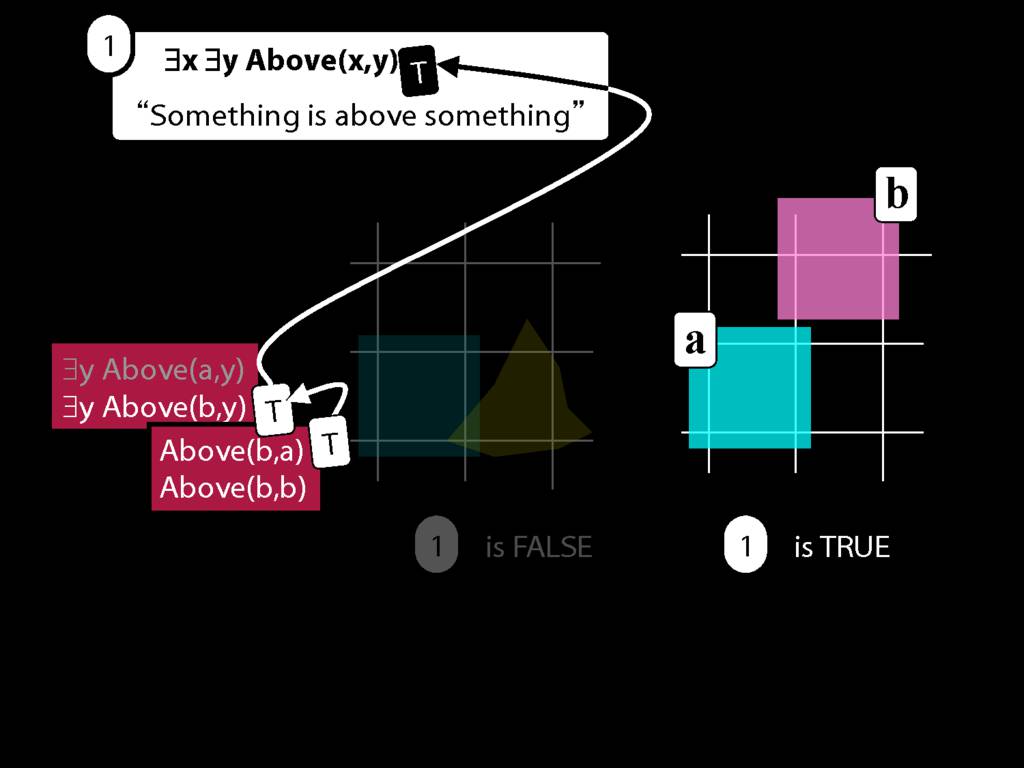

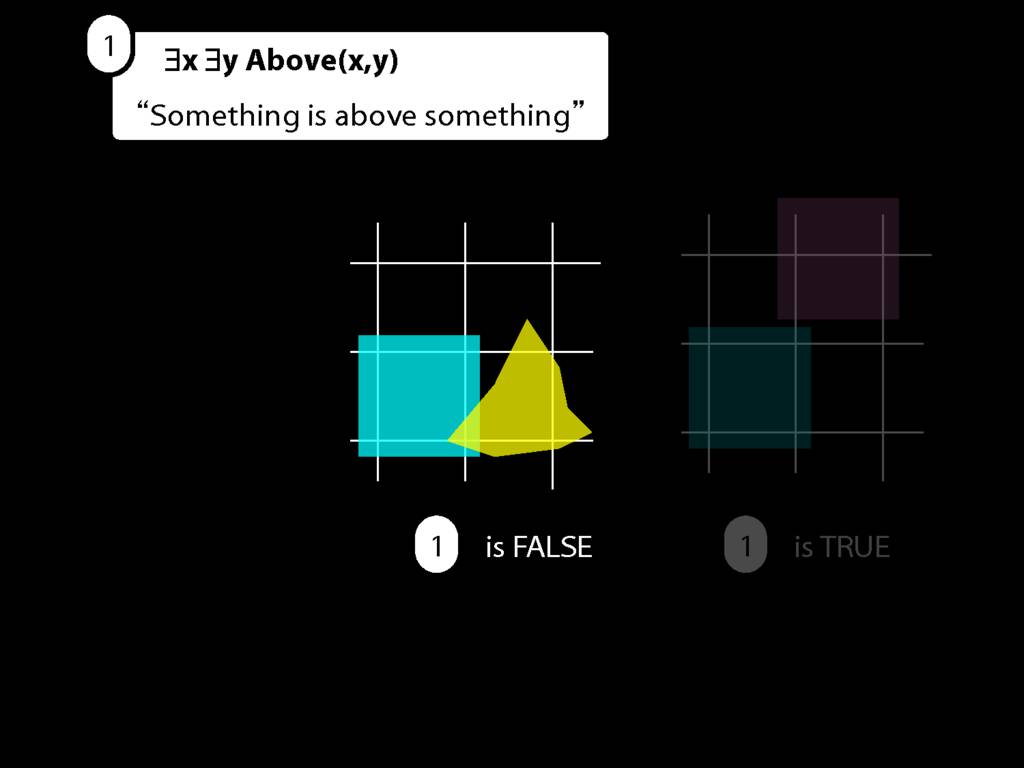

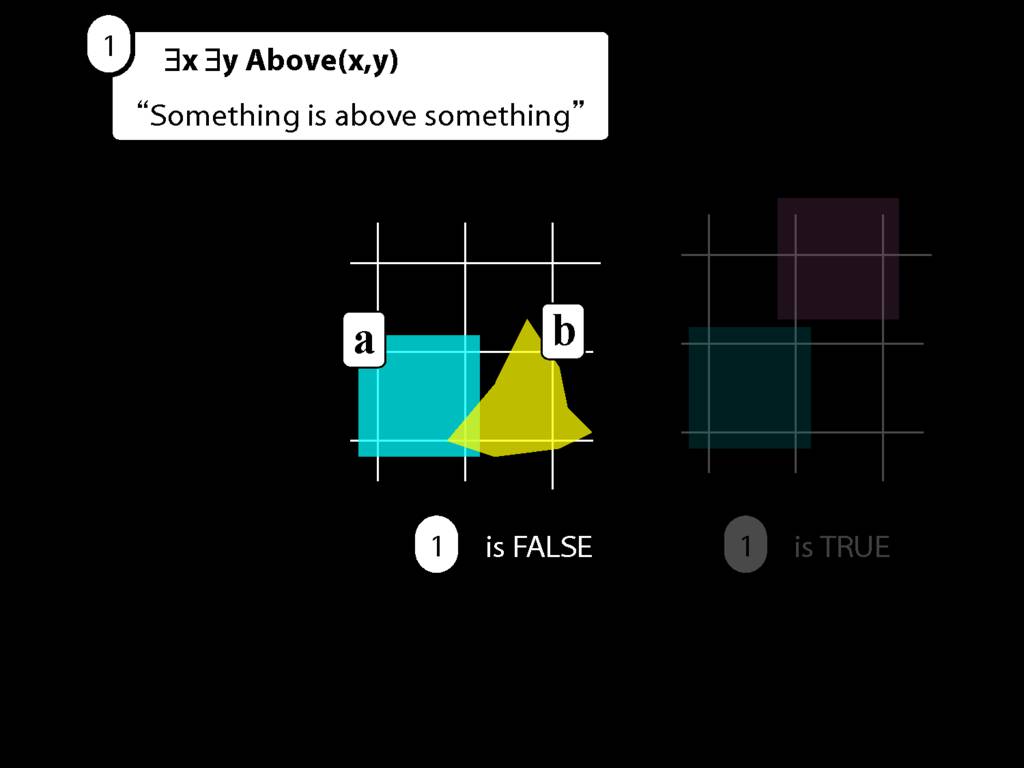

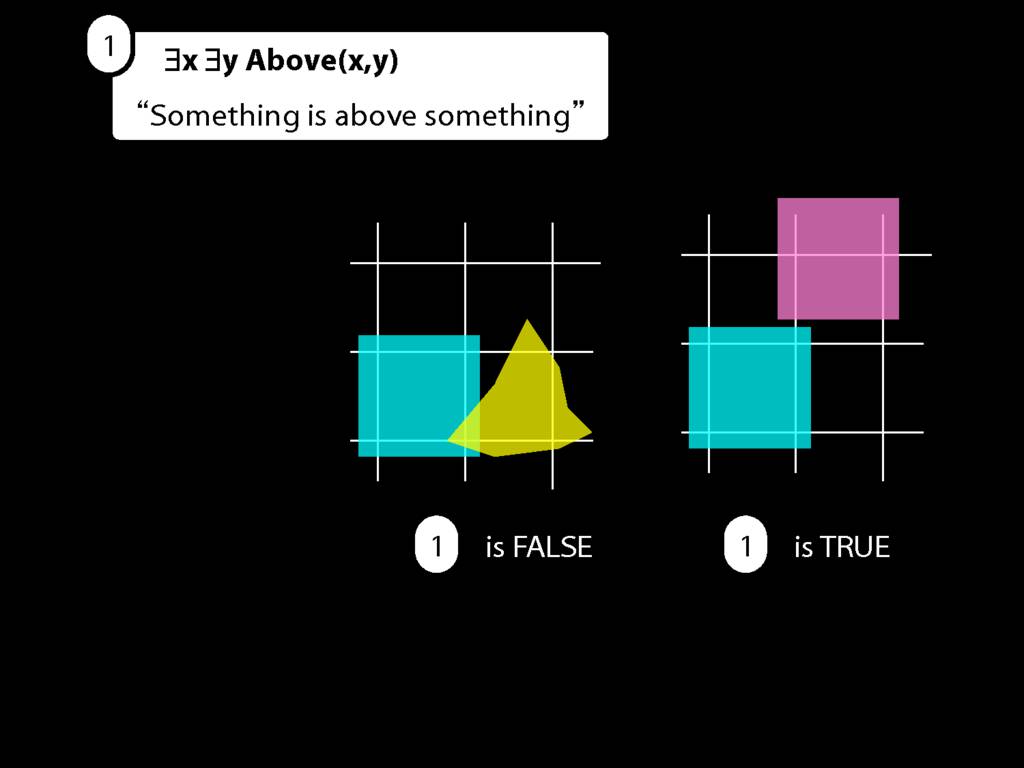

Something Is Above Something

So how can we start thinking about sentences with multiple quantifiers in our formal language, awFOL?

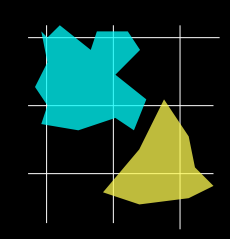

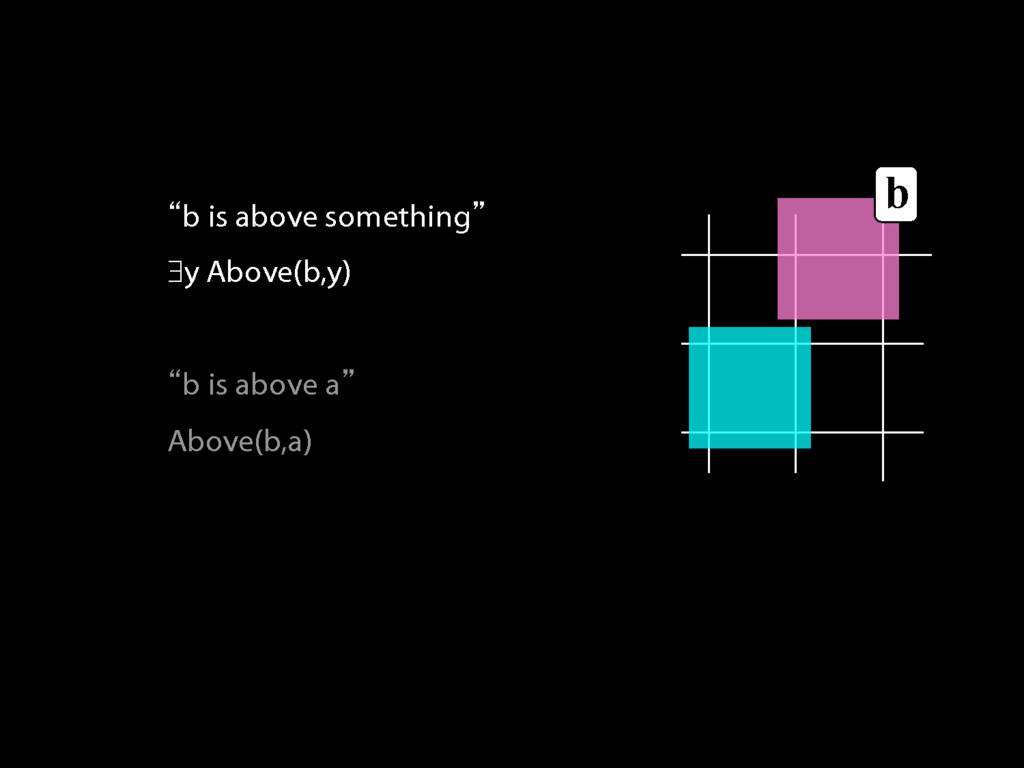

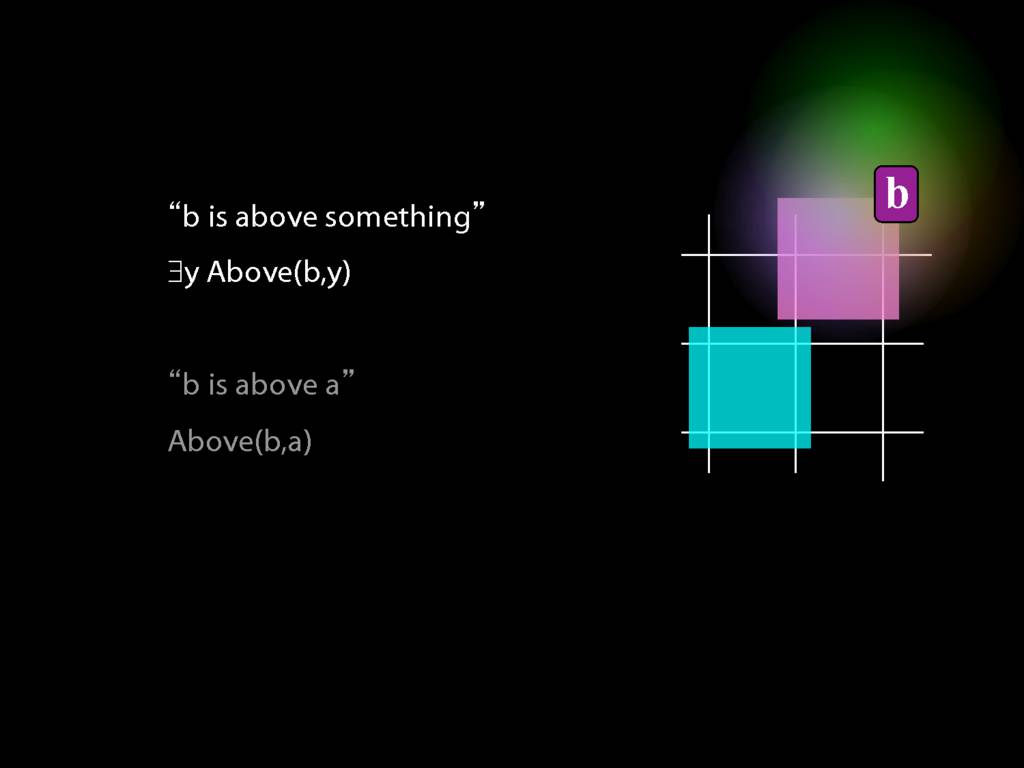

\begin{minipage}{\columnwidth}

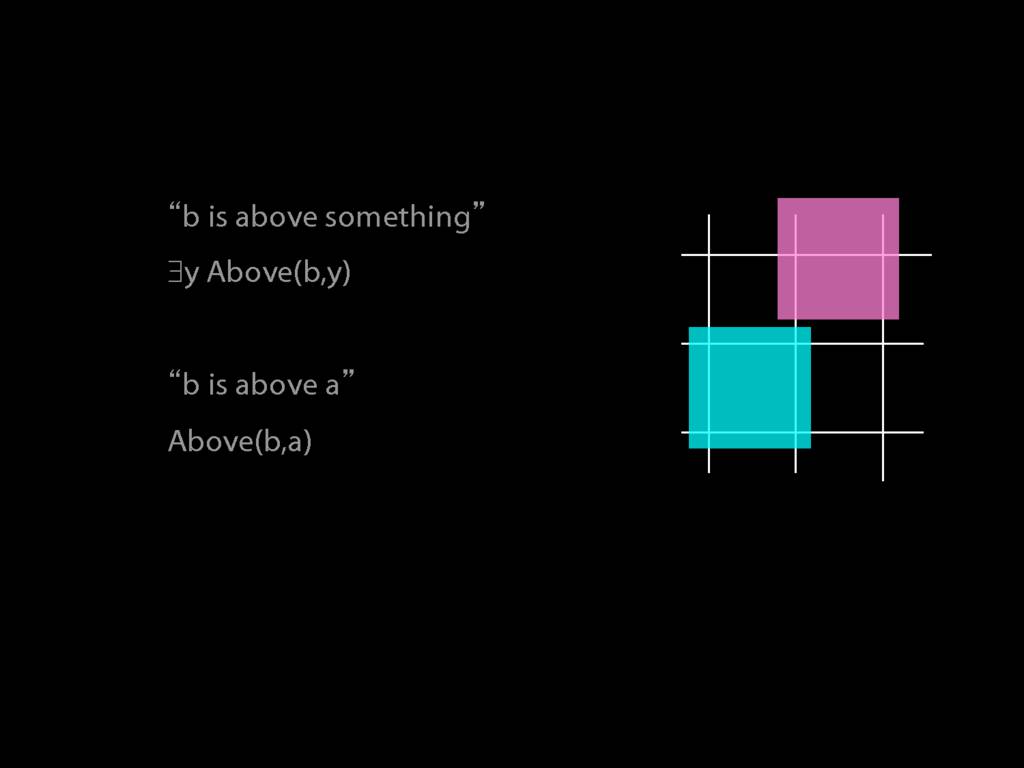

Something is above something:

\hspace{3mm} ∃x ∃y Above(x,y)

\end{minipage}

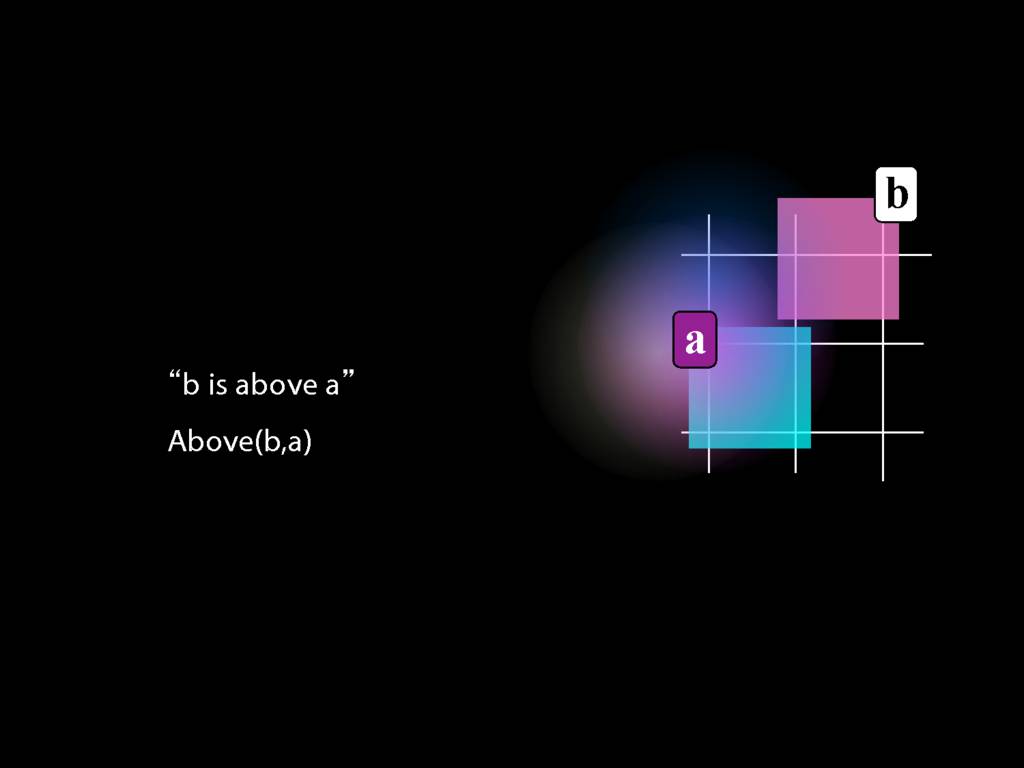

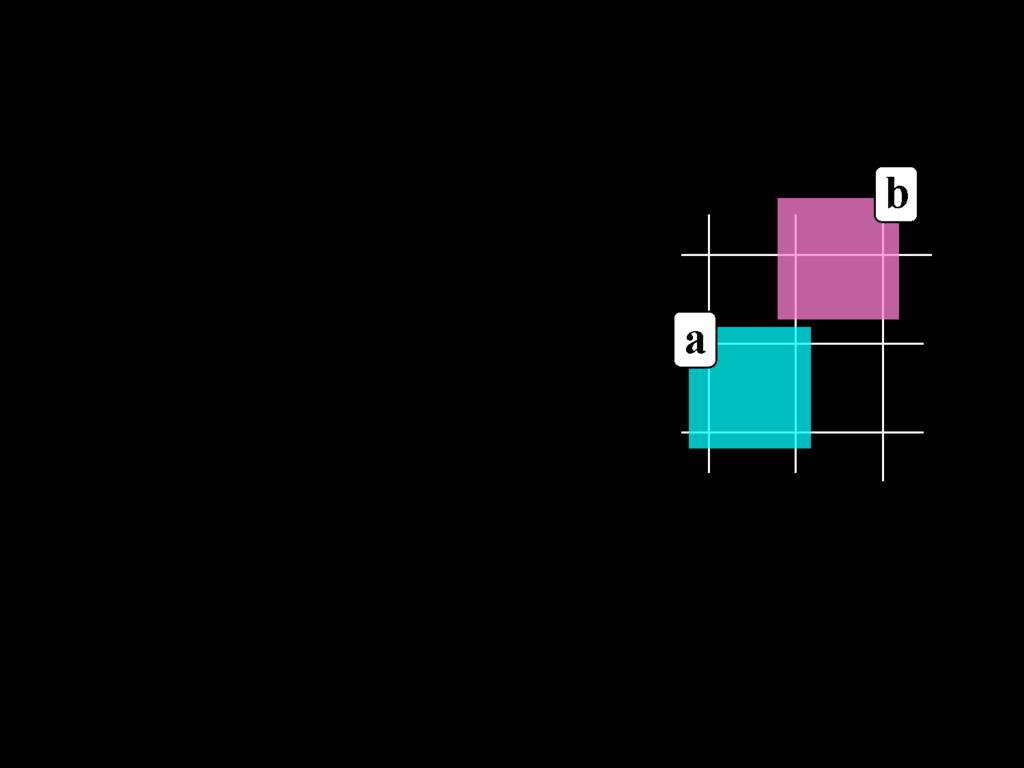

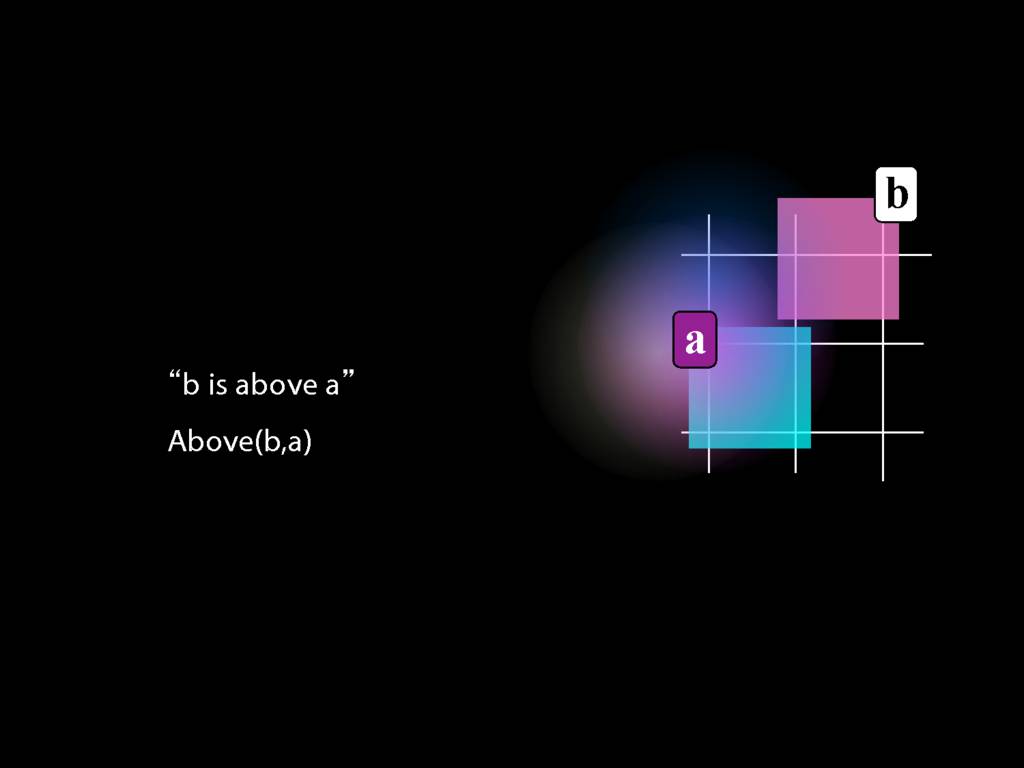

Here's a very simple possible situation in which b is above a.

Now suppose that we lost the name a.

Actually, we didn't really lose it. There were some terrorists, the logical equivalent of Hezbollah,

(here they are pictured in Southern Lebanon looking all military and disciplined)

and they were taking a break from doing their good work for Bashar Assad in his war on Syria

and Bashar had given them some cool weapons

and they were like, let's destroy the name a.

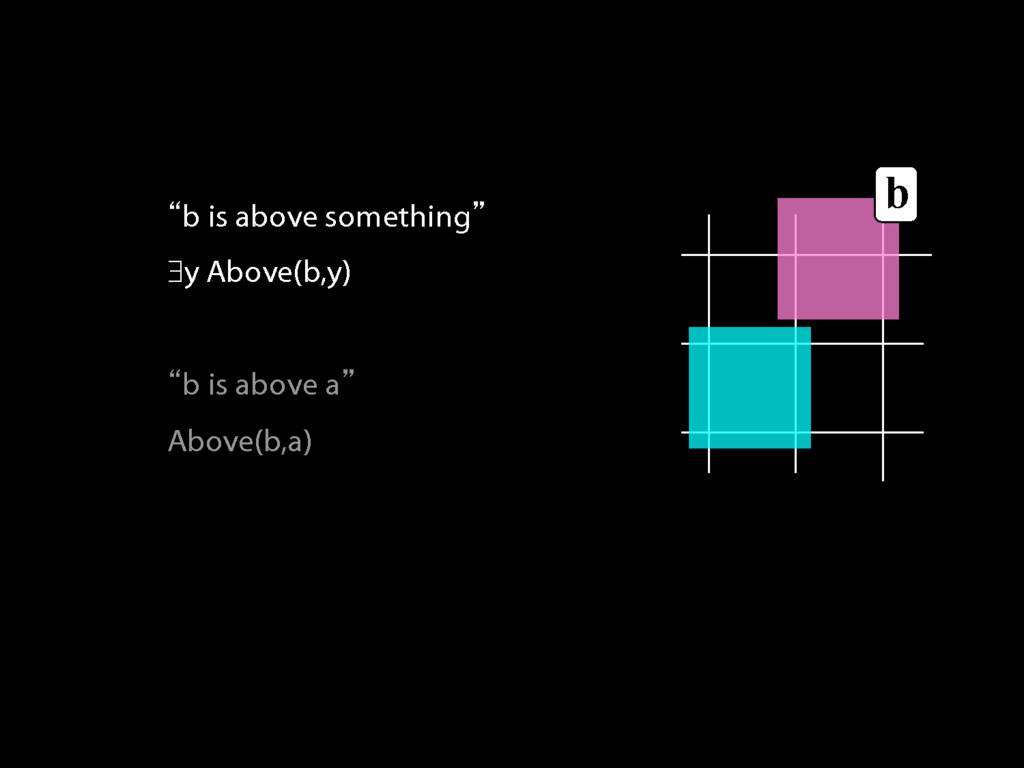

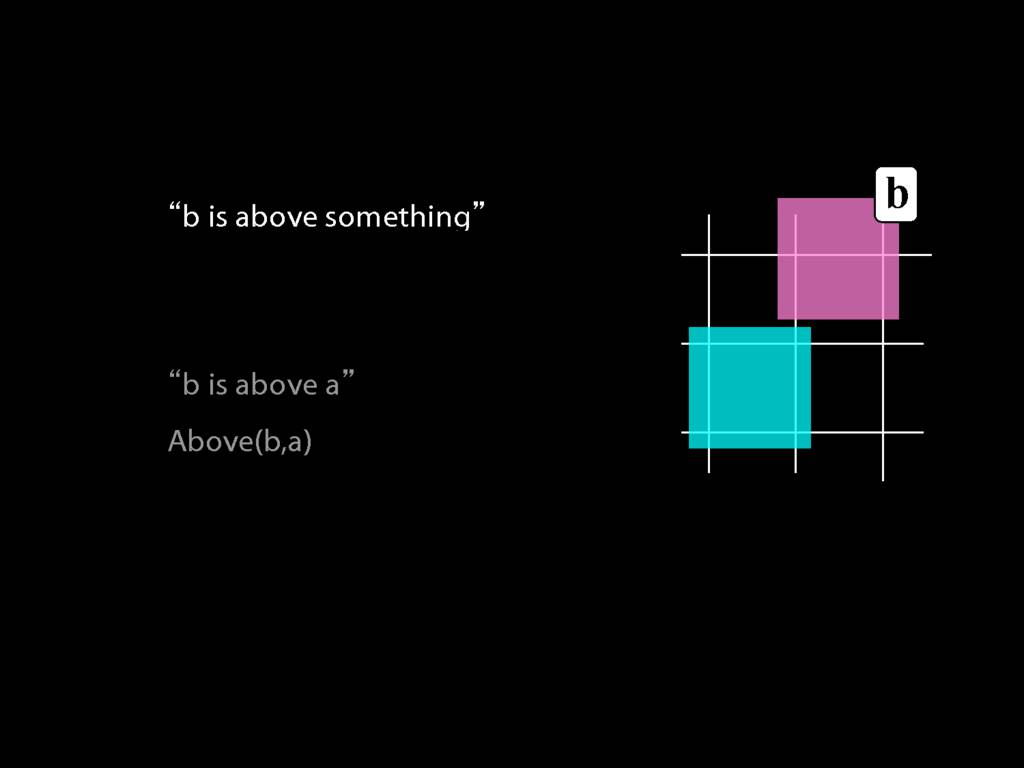

So we can't say b is above a anymore. We can only say that b is above something.

Luckily we know how to do this. We just drop the a, replace it with a variable (in this case, y), and add an existential quantifier.

Why existential? Because we're talking about something, not everything.

But look what happened next.

This time is wasn't Hezbollah.

It was my terrible twins, just back from training with the taliban.

(You may laugh but it's just very hard to get quality childcare without religion these days.)

Yes, and they destroyed the name b.

So now we can't name that object either, we can only say that something is above something.

But, look, we already know how to do this. We just remove the name b from the sentence we last had, replace it with a variable (in this case, x) and add an existential quantifer out the front.

Now we've got a sentence with multiple quanifiers without doing anything new, just replacing names with quantifiers.

Let's consider translation the other way, from awFOL back to English.

Do we understand this sentence of awFOL?

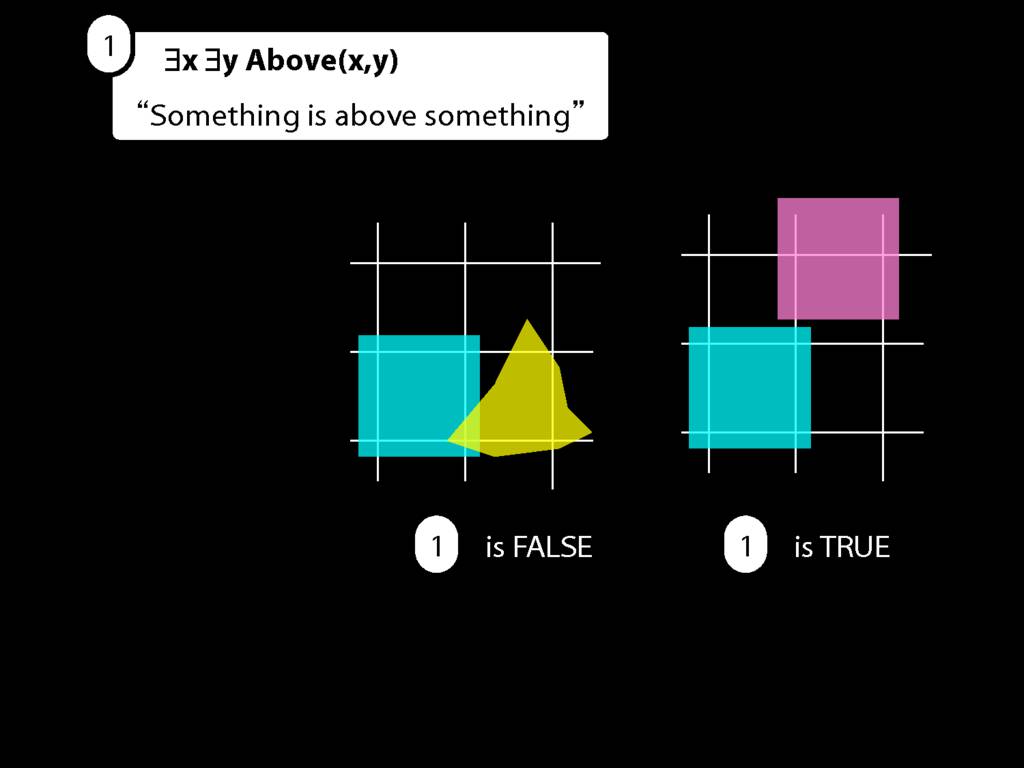

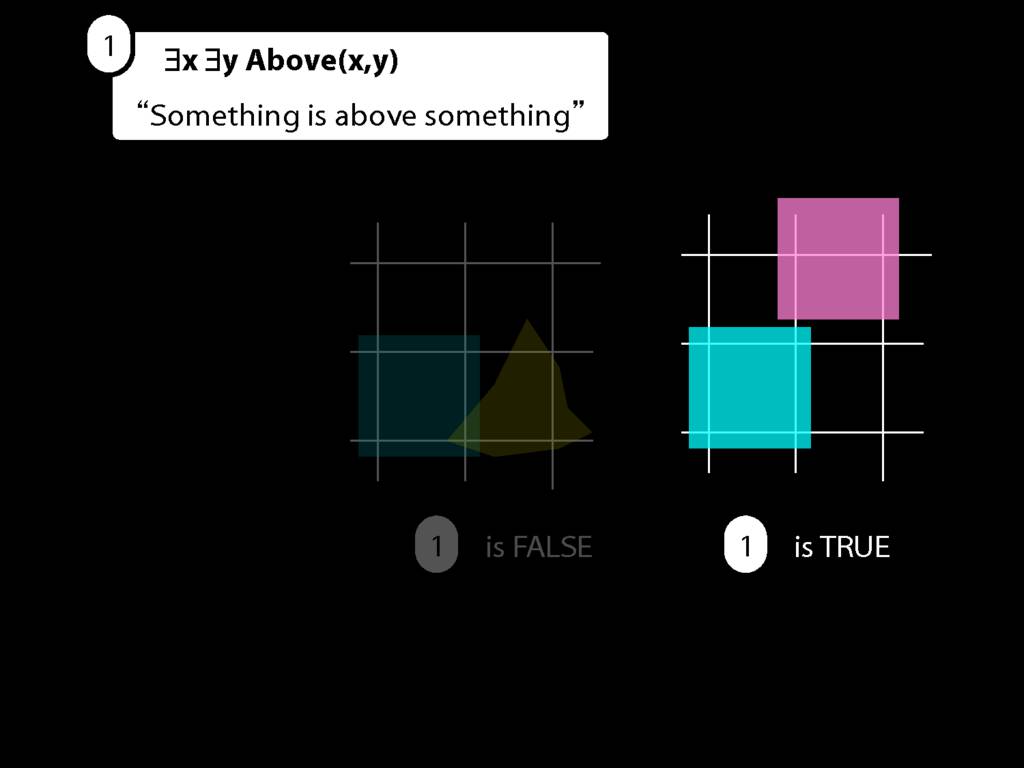

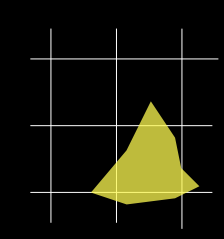

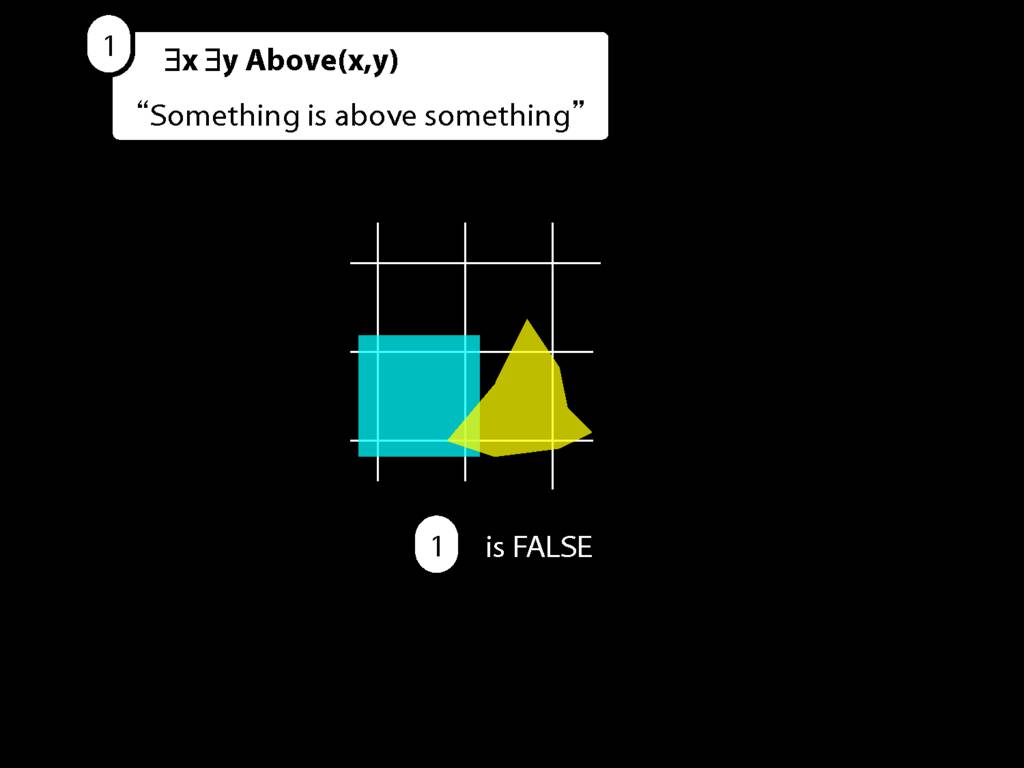

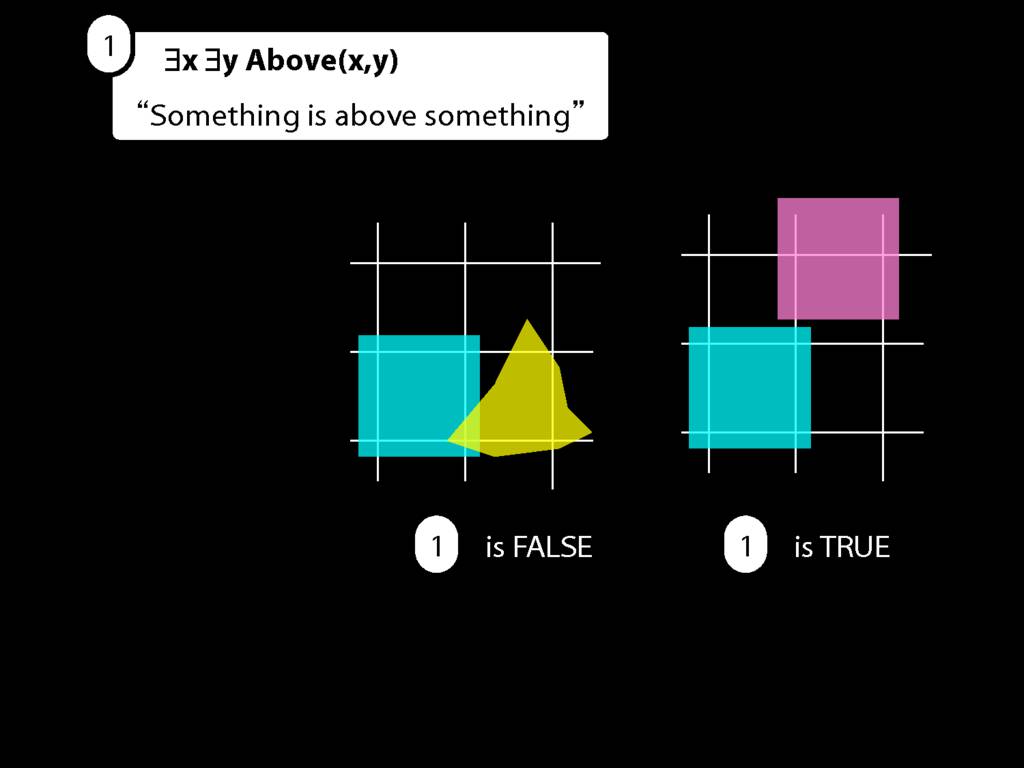

Well, is it true in this possible situation?

And is it true in this possible situation? How do we know?

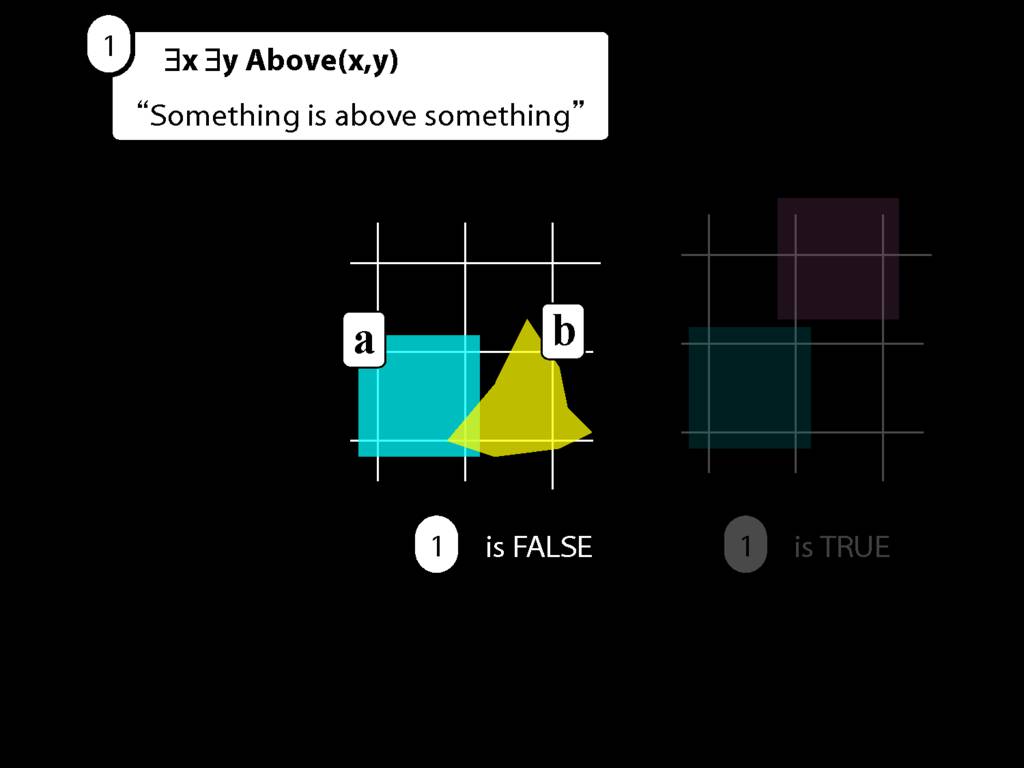

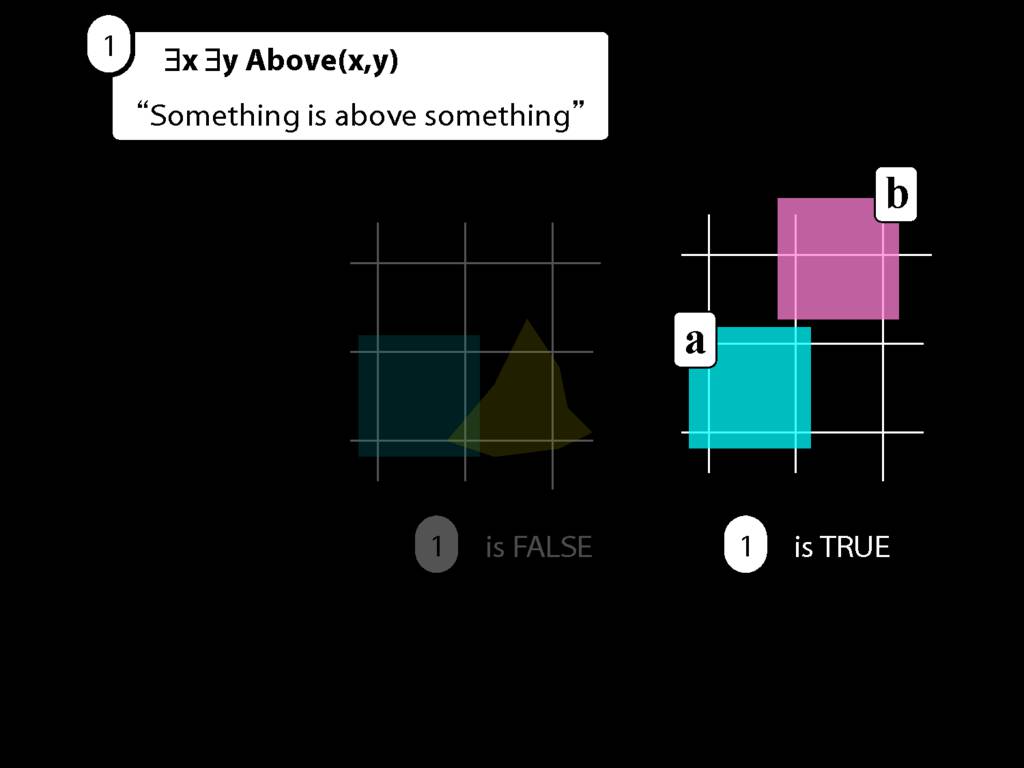

Take this possible situation first.

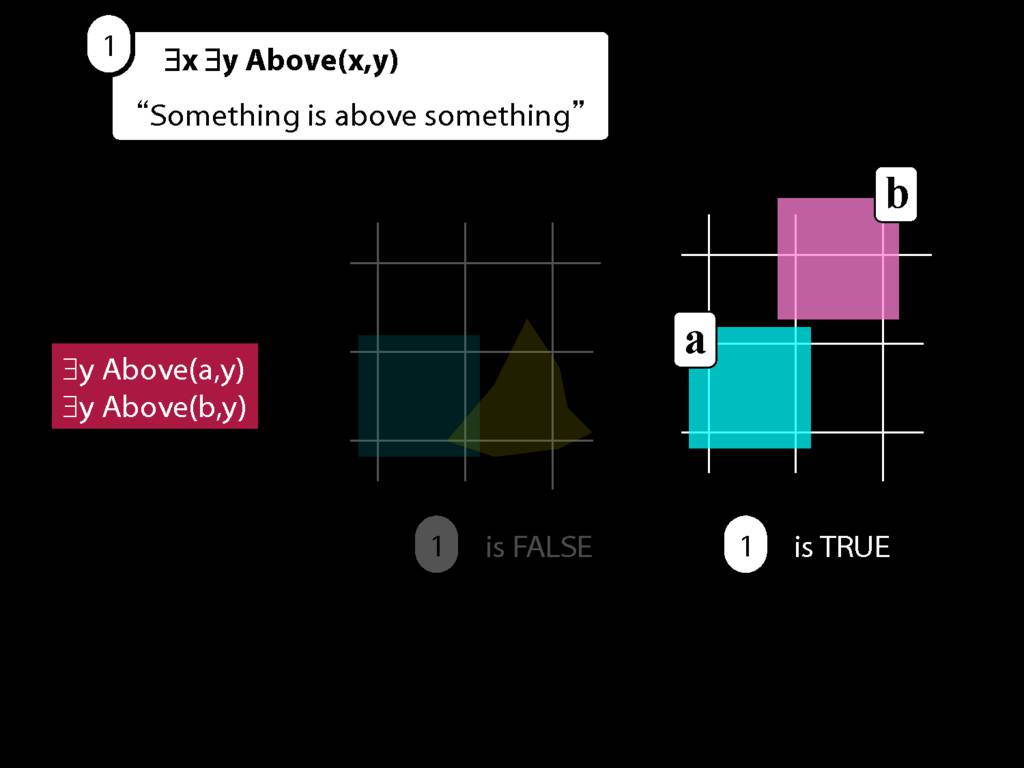

There is a procedure for determining the truth or falsity of an existentially quantified sentence.

We first give every object a name.

In this possible situation there are two objects so there we assign two names.

(Look, here are a and b again. I guess they weren't destroyed forever. Maybe we had a little war on terror and got them back.)

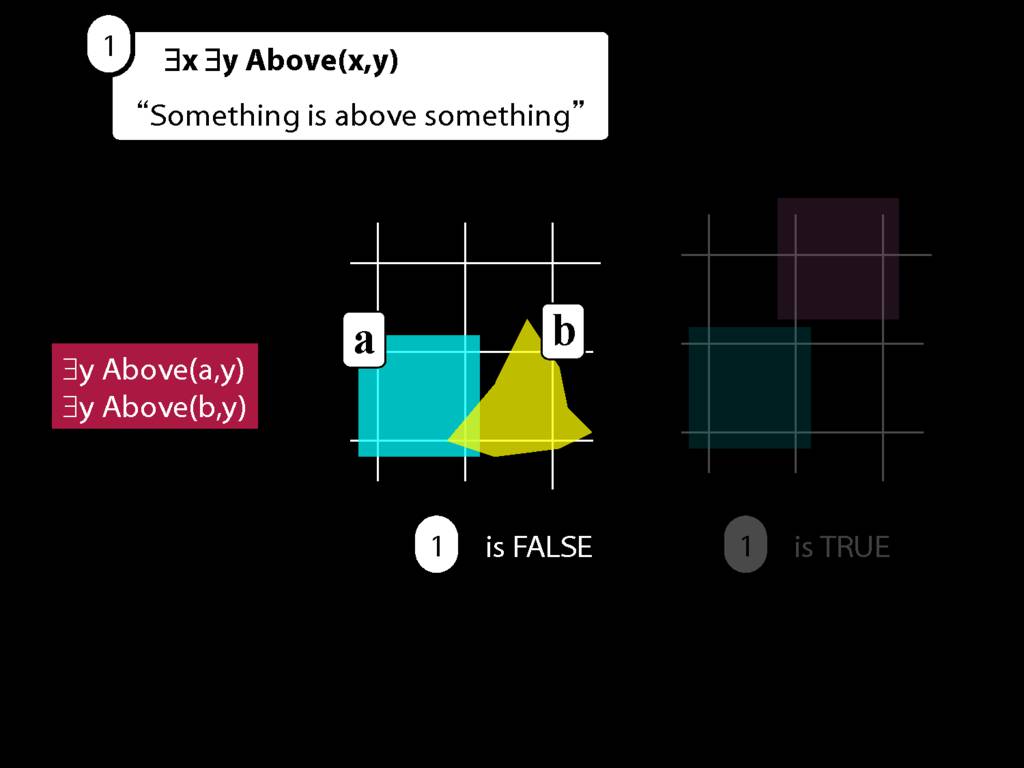

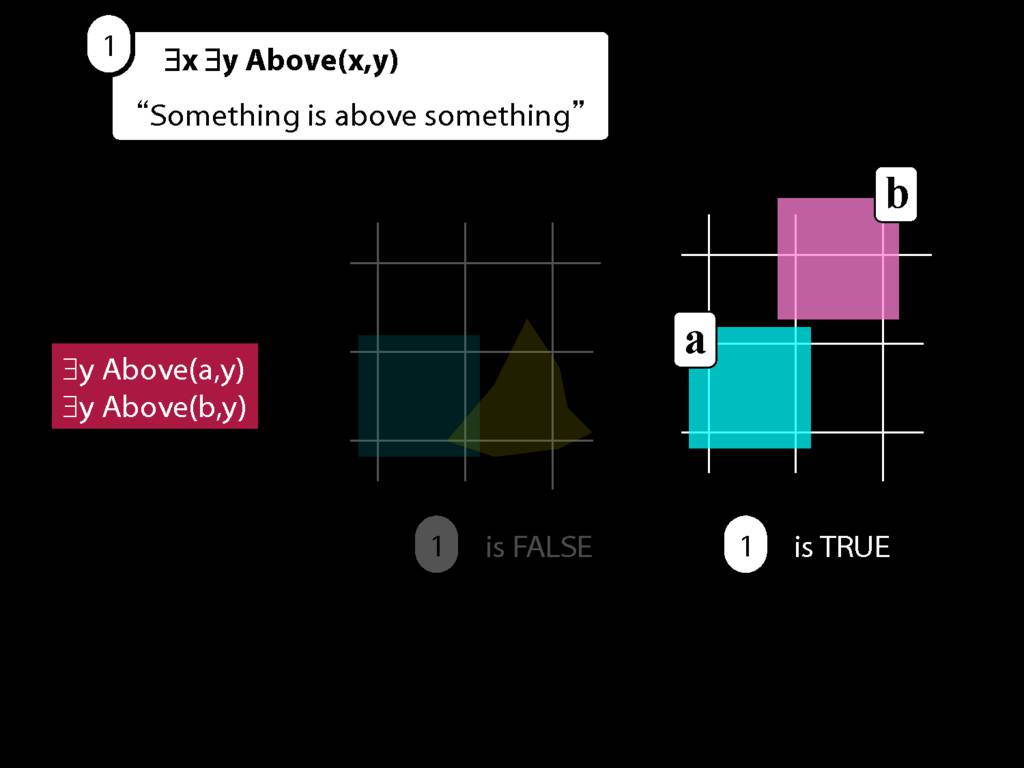

Then we make new sentences by removing an existential quantifier and replacing the variable with each name in turn.

Look here: two objects so two names so two sentences.

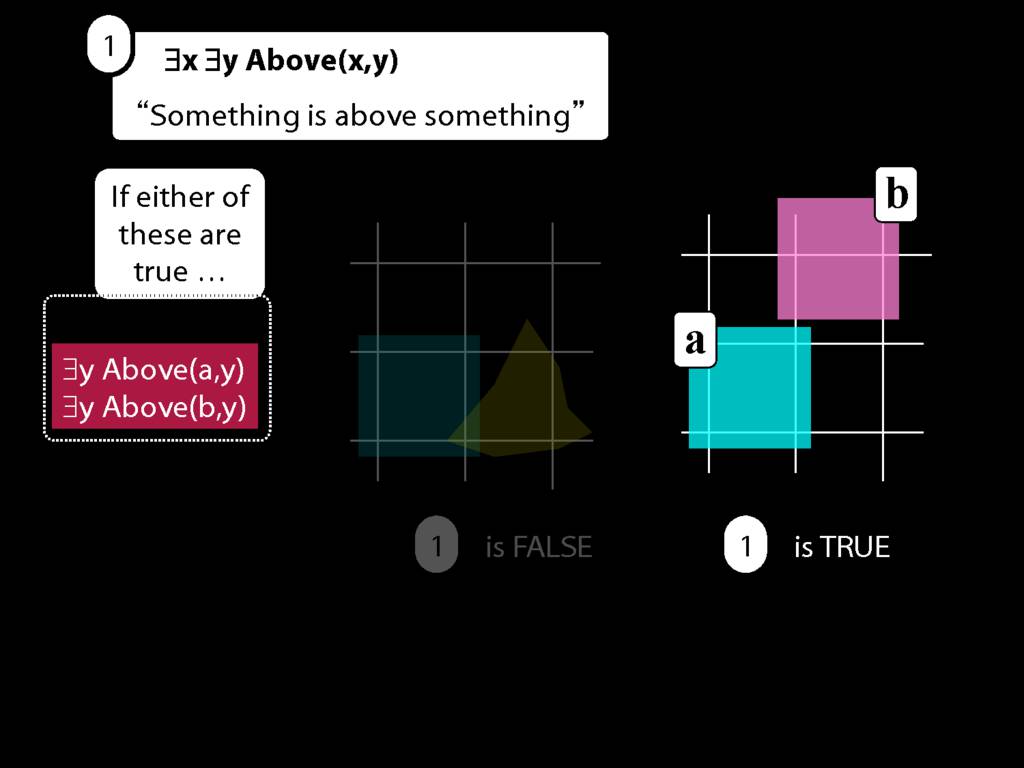

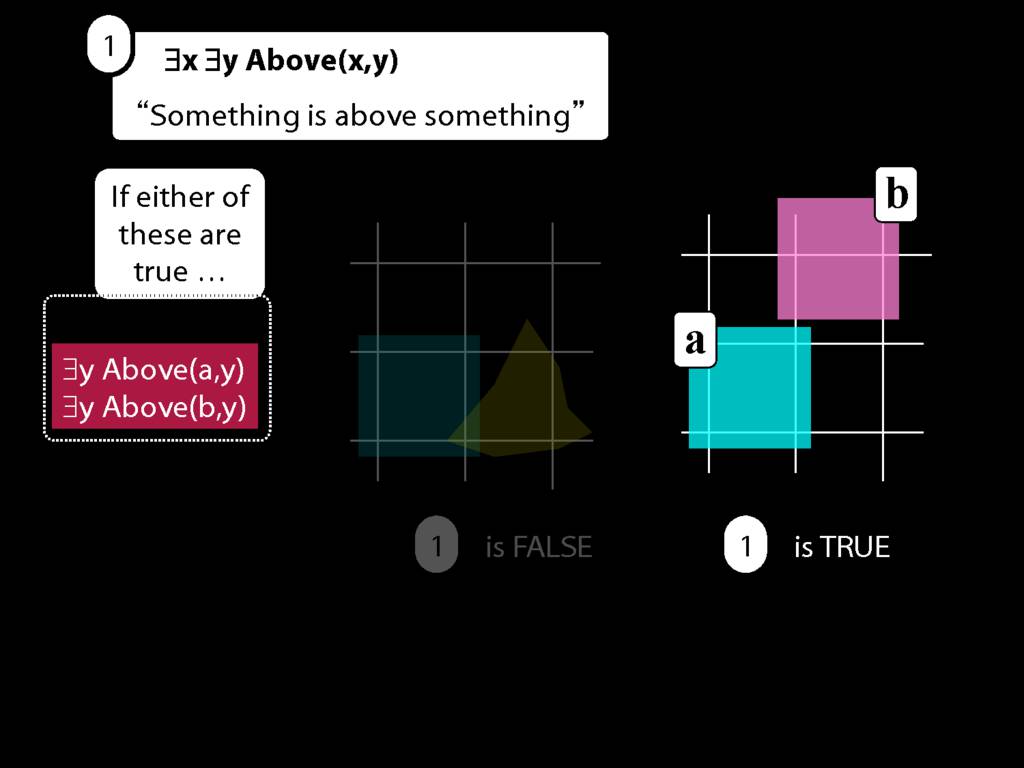

Now if either of these are true, ...

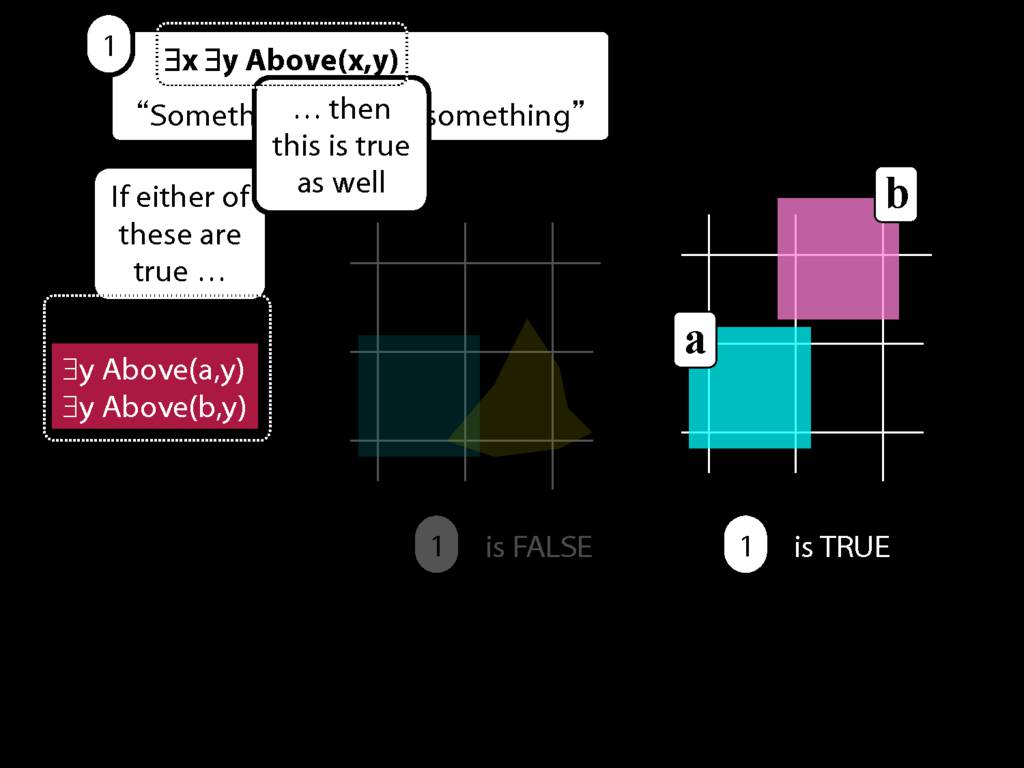

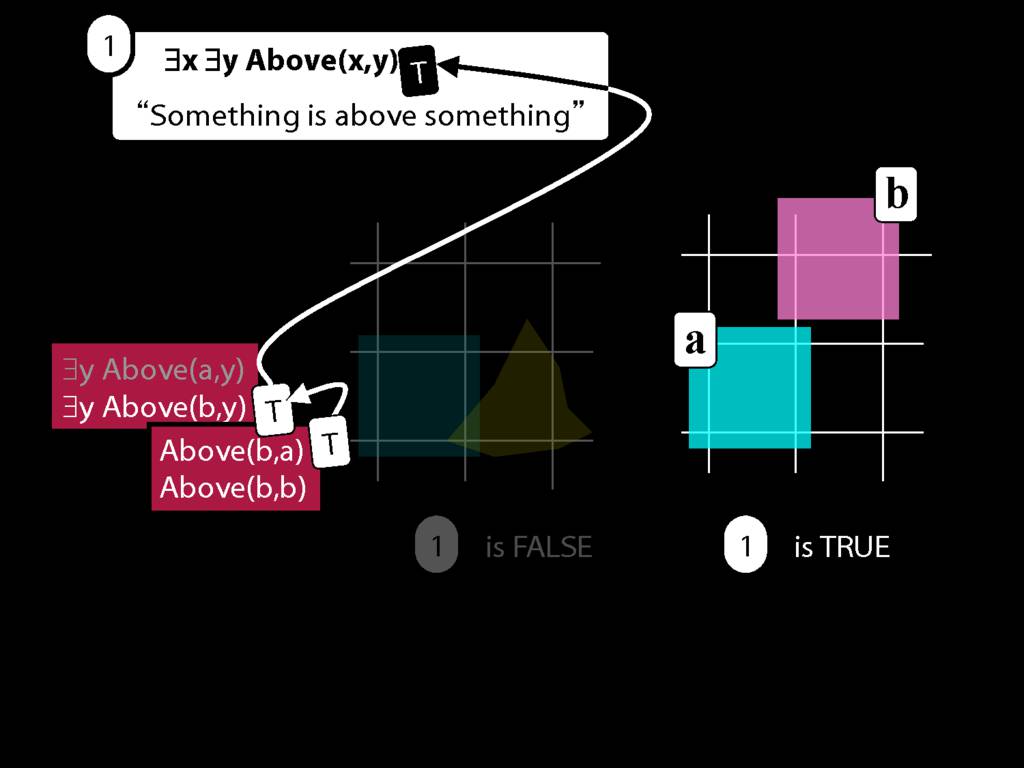

... then so is the sentence we started with, ∃x ∃y Above(x,y).

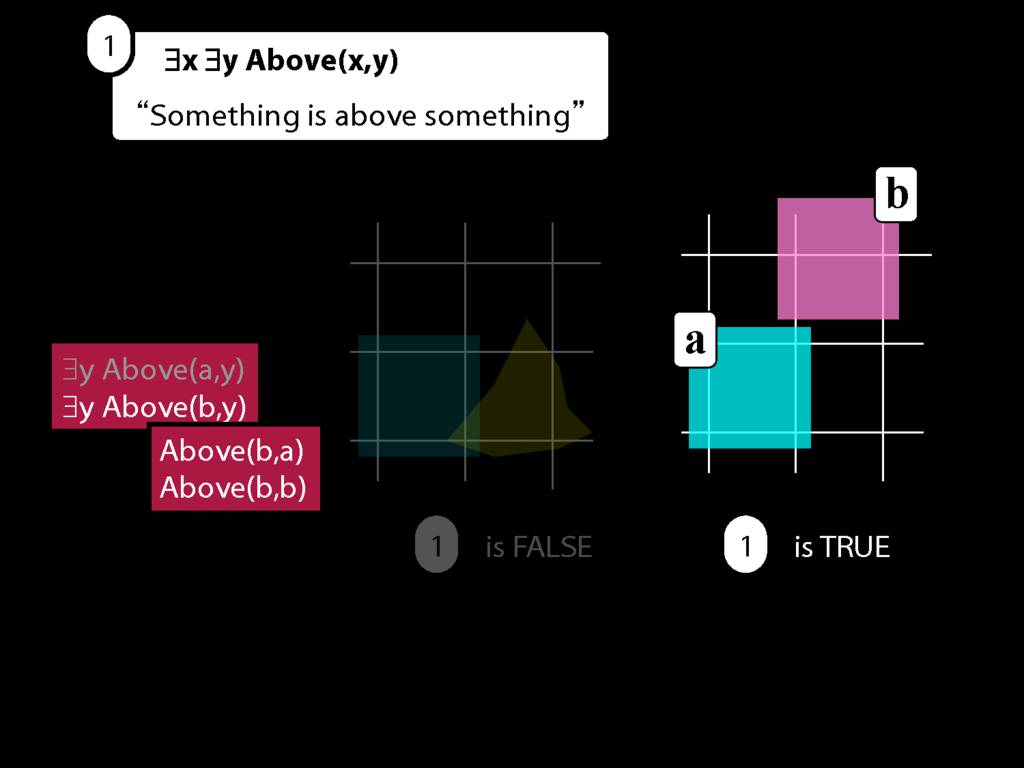

But what does it take for one of these to be true?

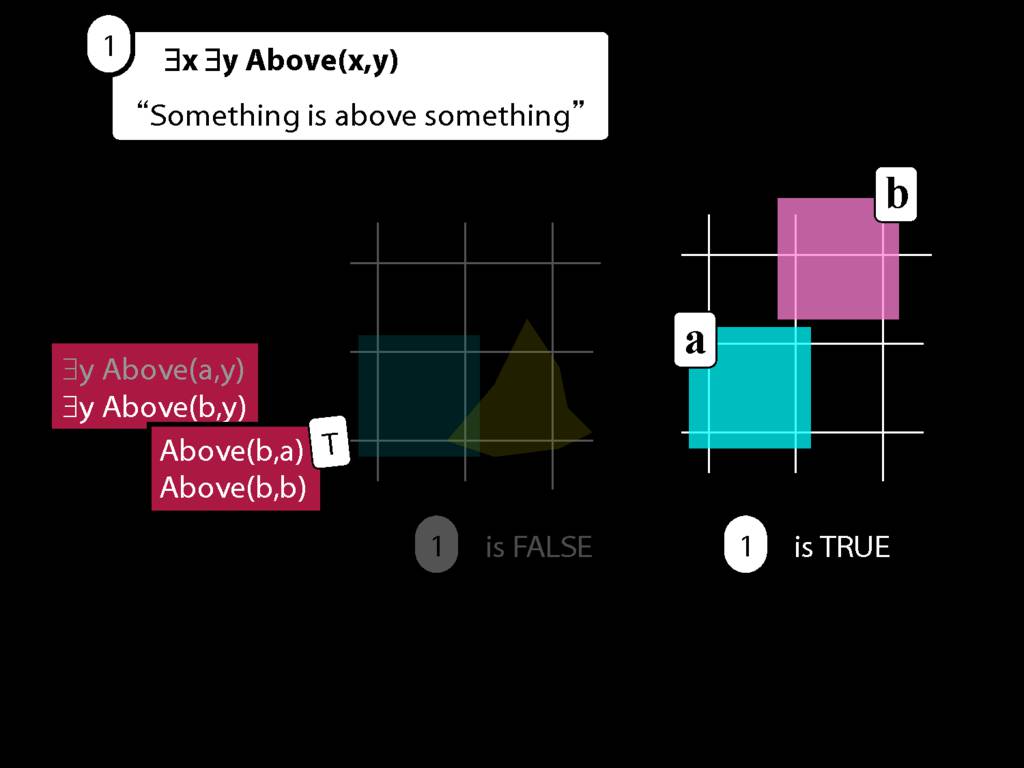

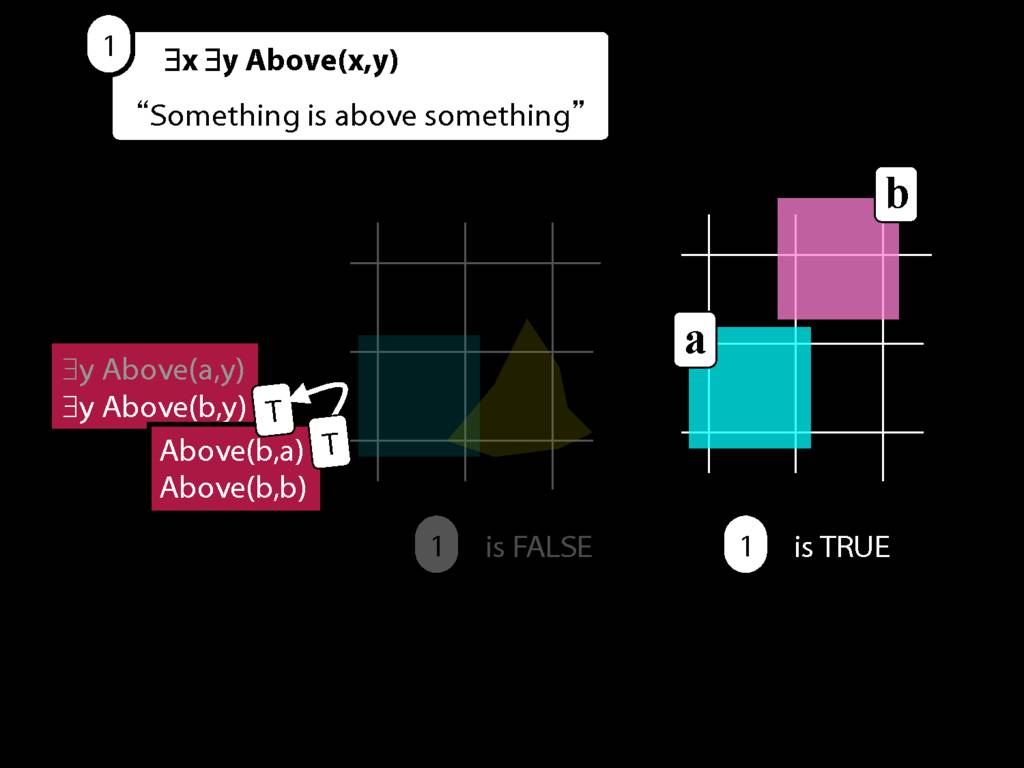

Consider the second.

To work out whether it's true we have to apply the same procedure again.

The first step is to give everything a name, but since everything already has a name there's nothing we need to do.

Then we make new sentences by removing an existential quantifier and replacing the variable with each name in turn.

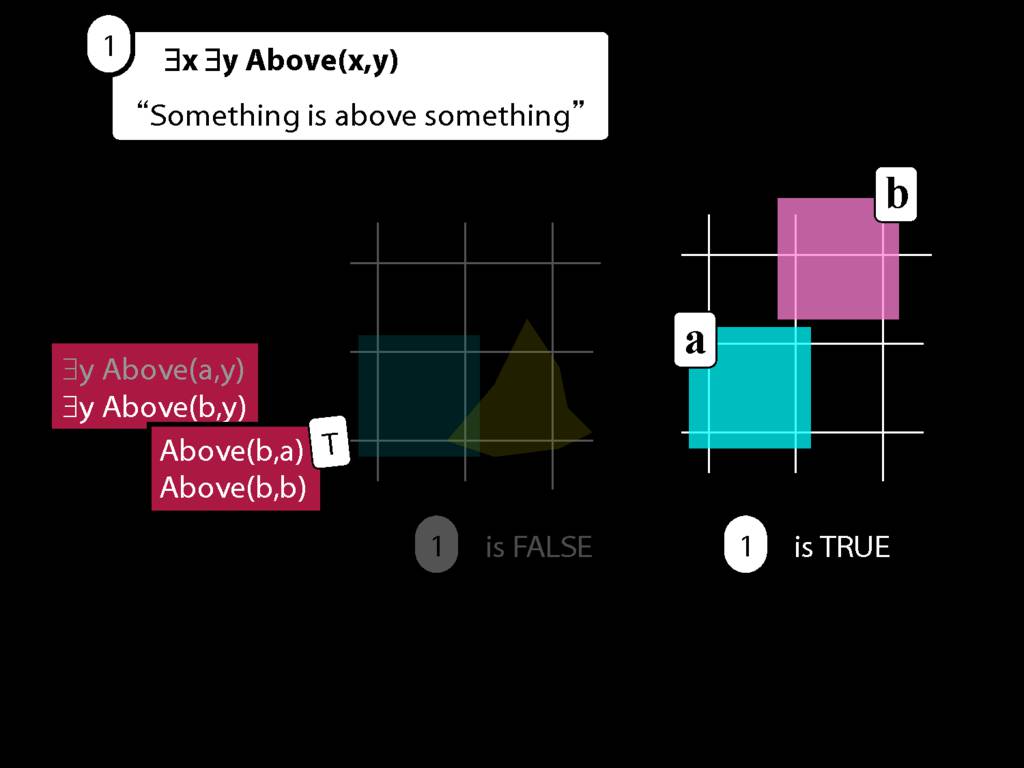

This gives us these new sentences, Above(b,a) and Above(b,b)

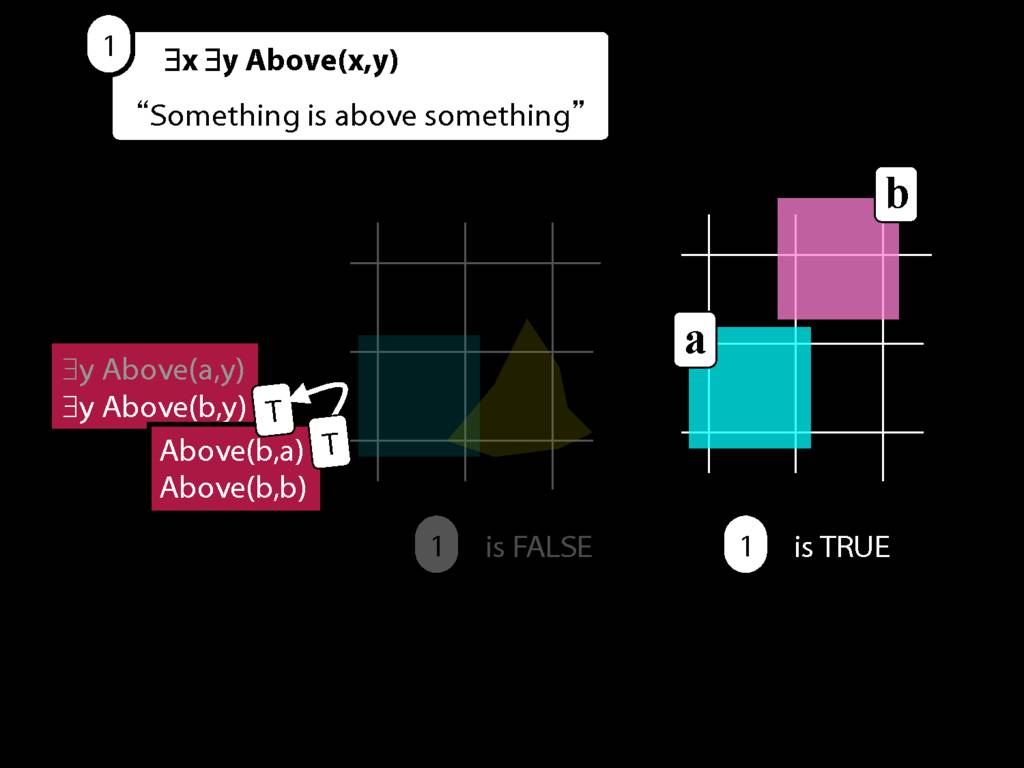

Now if either of these are true, then so is the sentence we started with, ∃y Above(b,y).

But the first of these is true!

This tells us that ∃y Above(b,y) is true.

And that tells us that ∃x ∃y Above(x,y) is true as well.

This is how we can understand sentences of awFOL involving multiple quantifiers.

To work out whether they are true, we apply the procedure for determining the truth of an existentially quantified statement removing just one quantifer.

And we keep applying these procedures until not quantifiers are left.

This is much like doing complex truth-tables.

Magic, no?

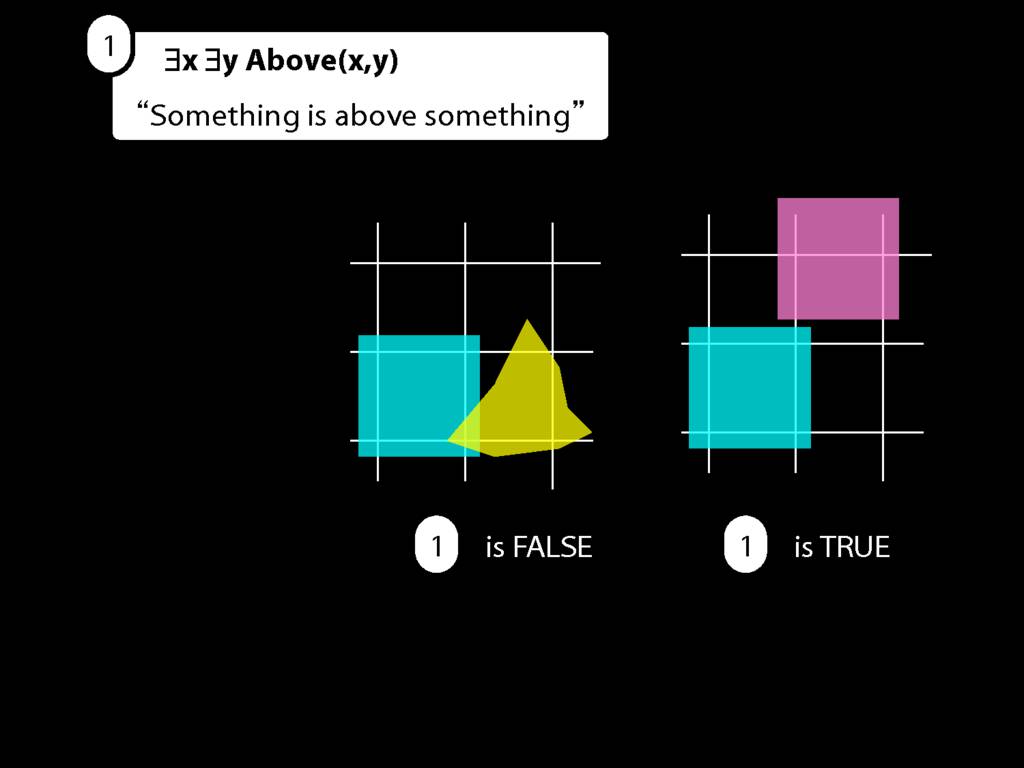

If you've been following along you should be able to do the same in any other possible situation like this one.

The procedure has three steps. First ... well, you know what the procedure is.

... and you can see whether the sentence is true or false.

11.2, 11.4

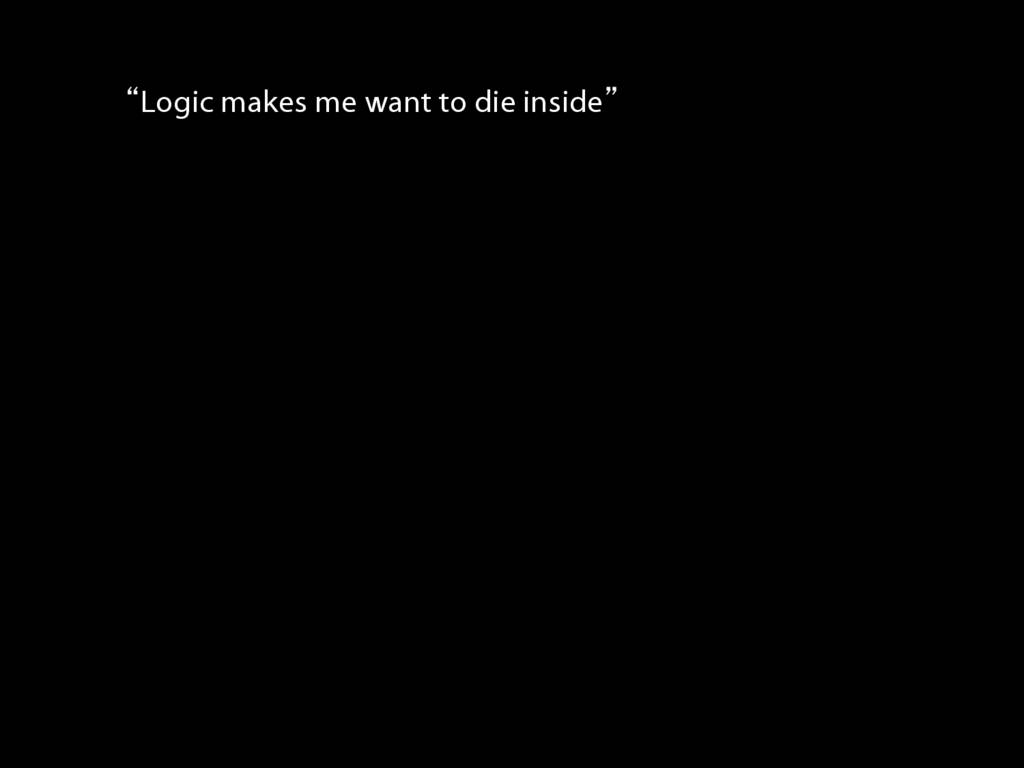

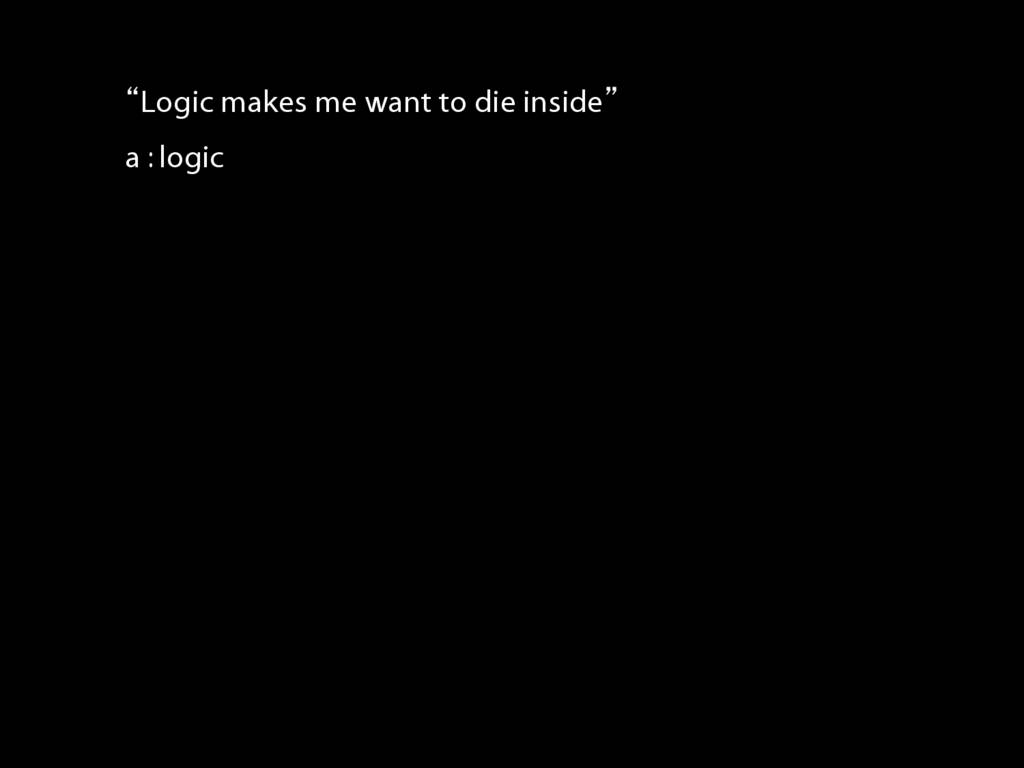

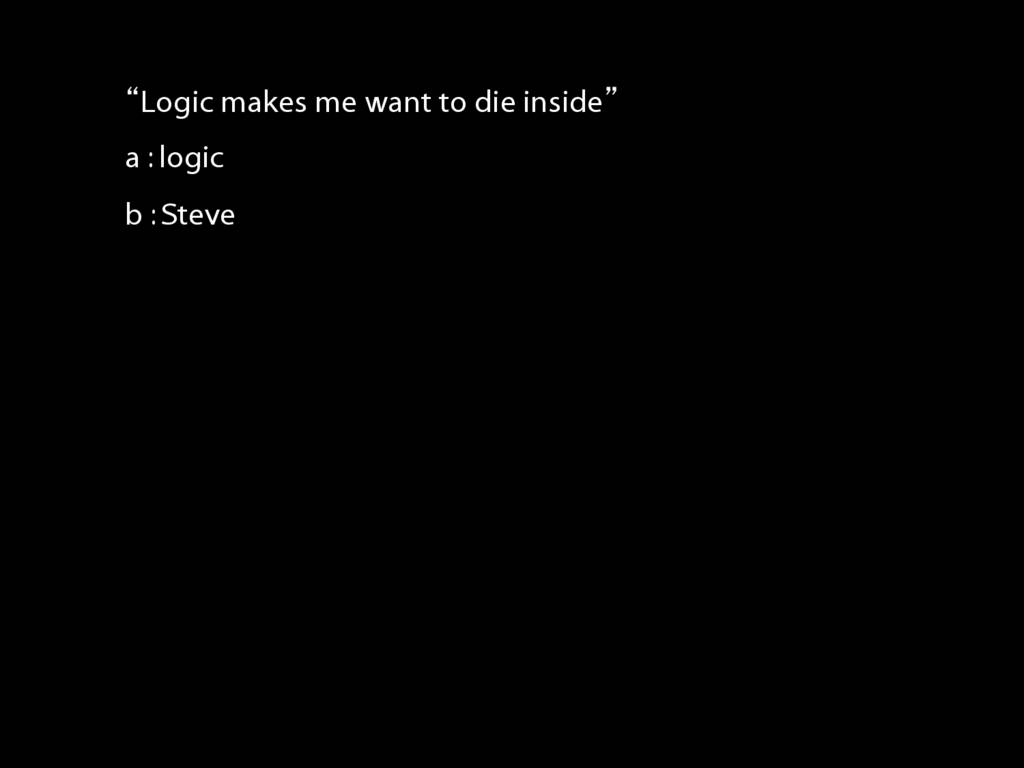

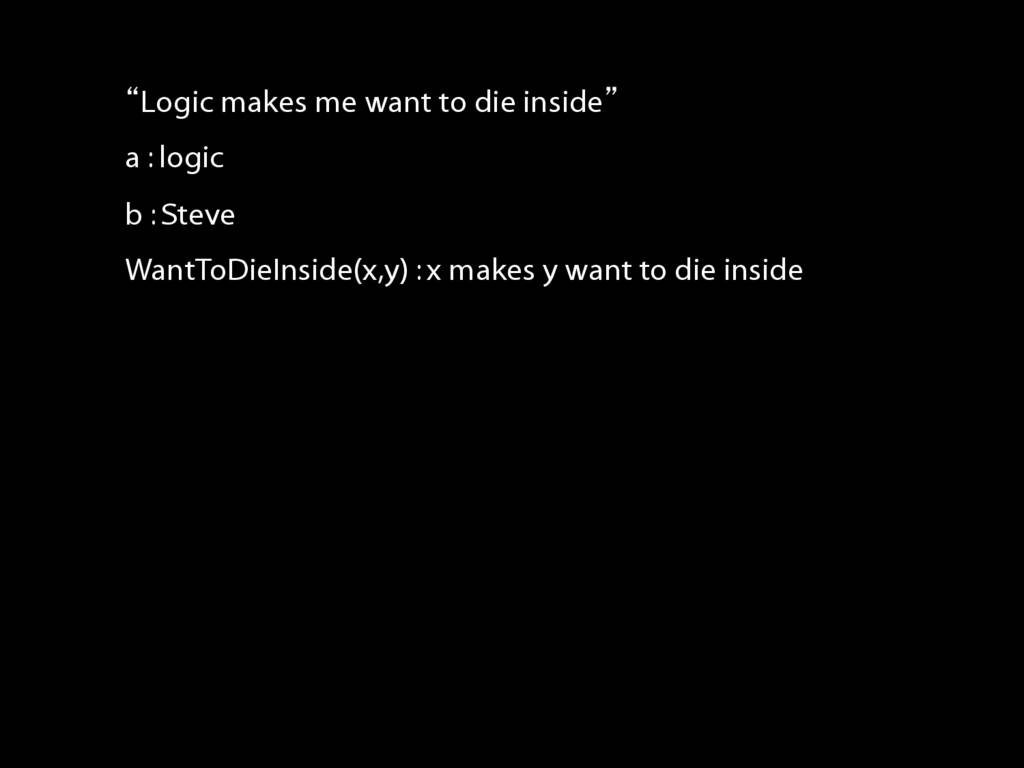

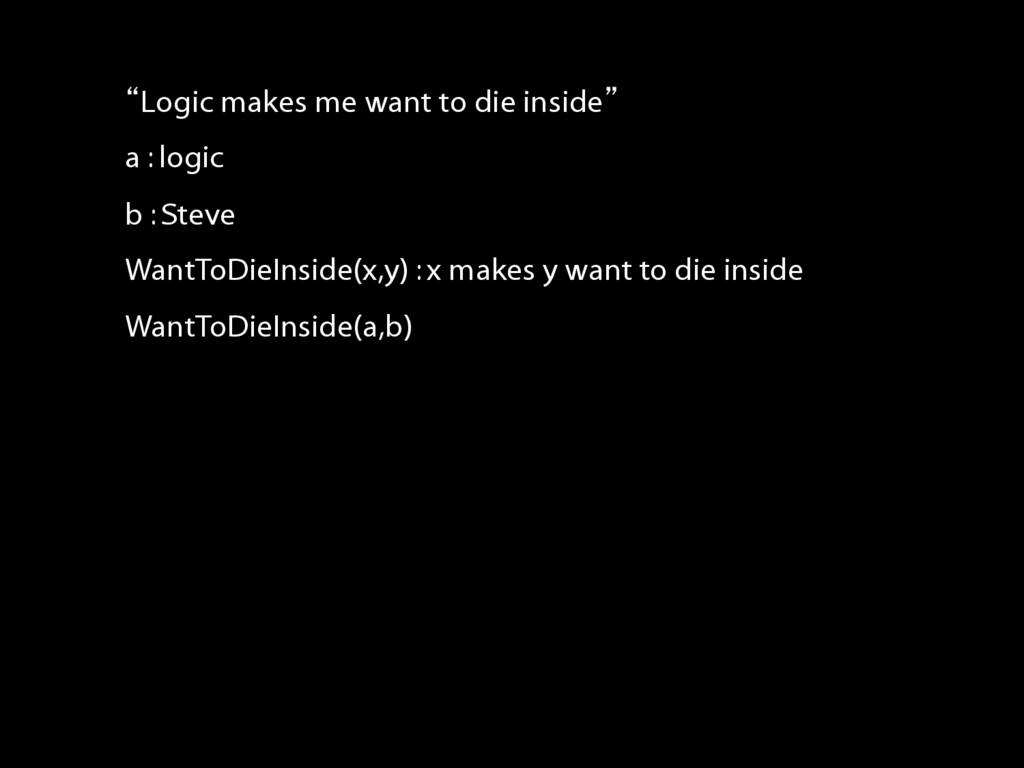

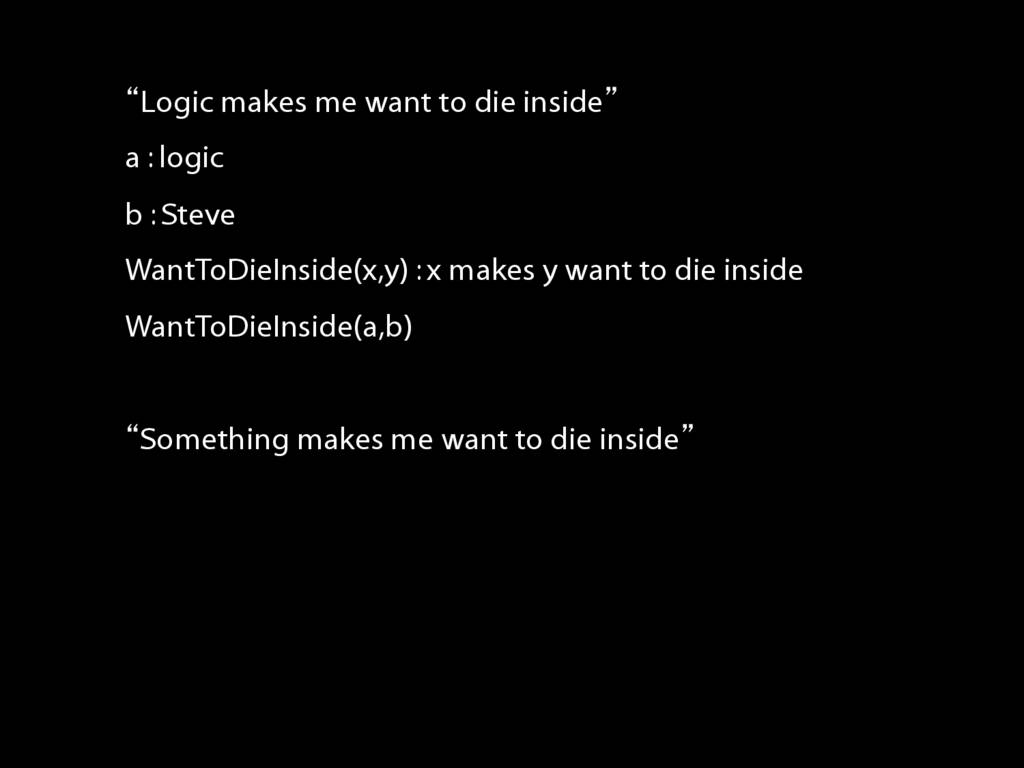

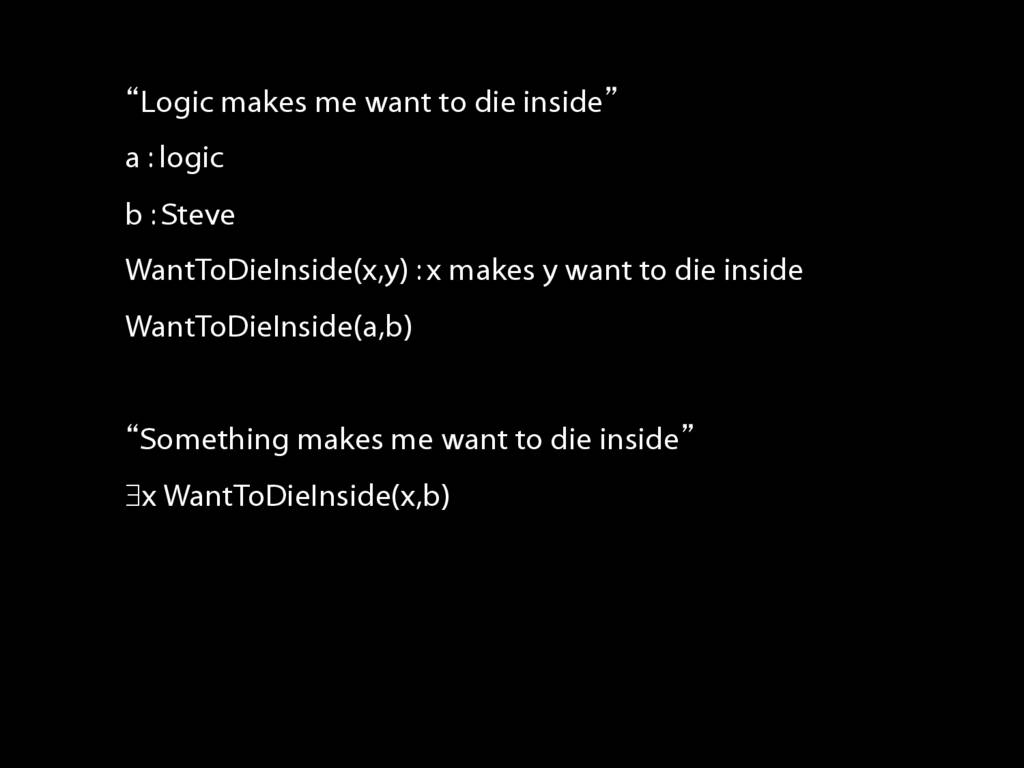

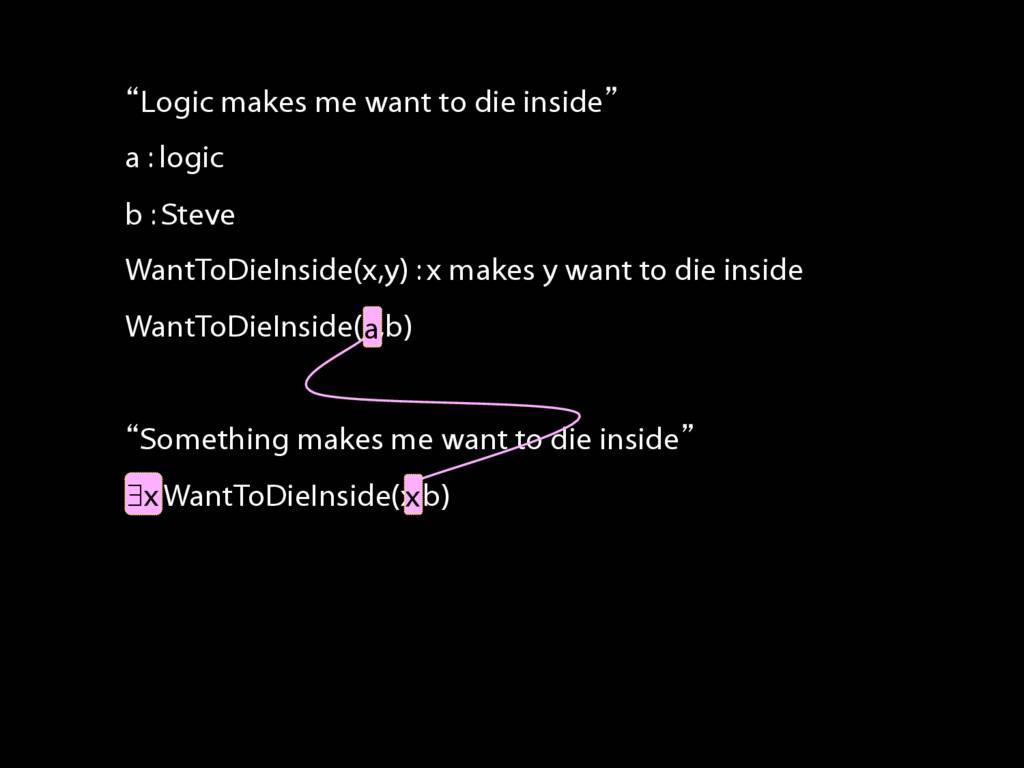

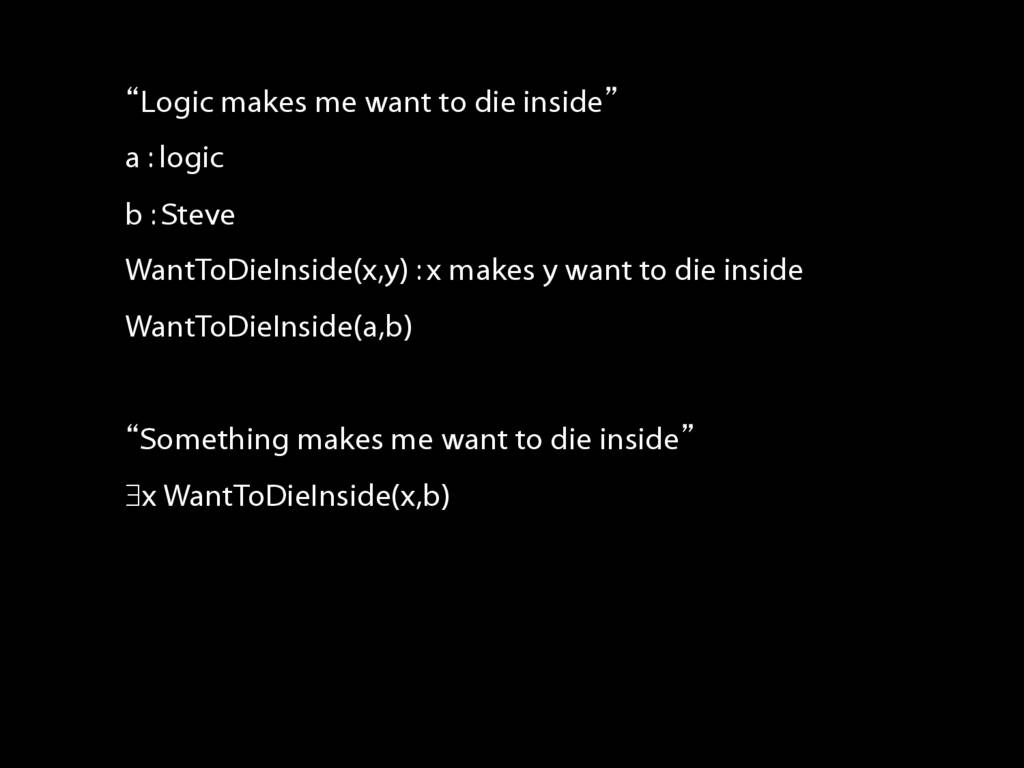

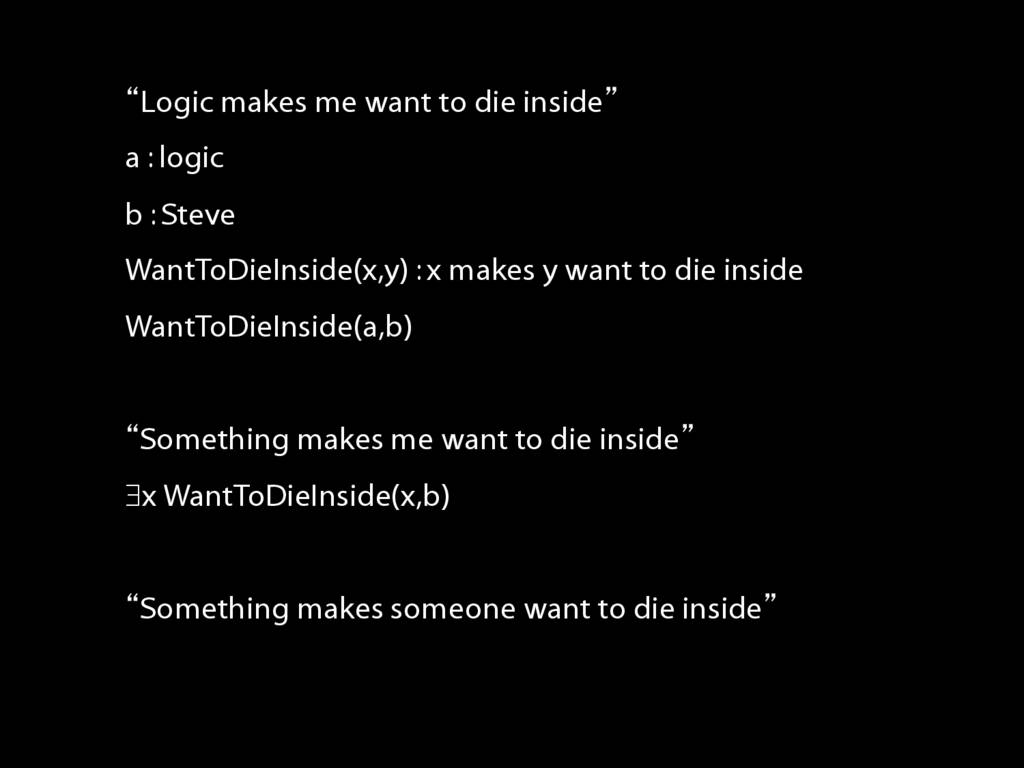

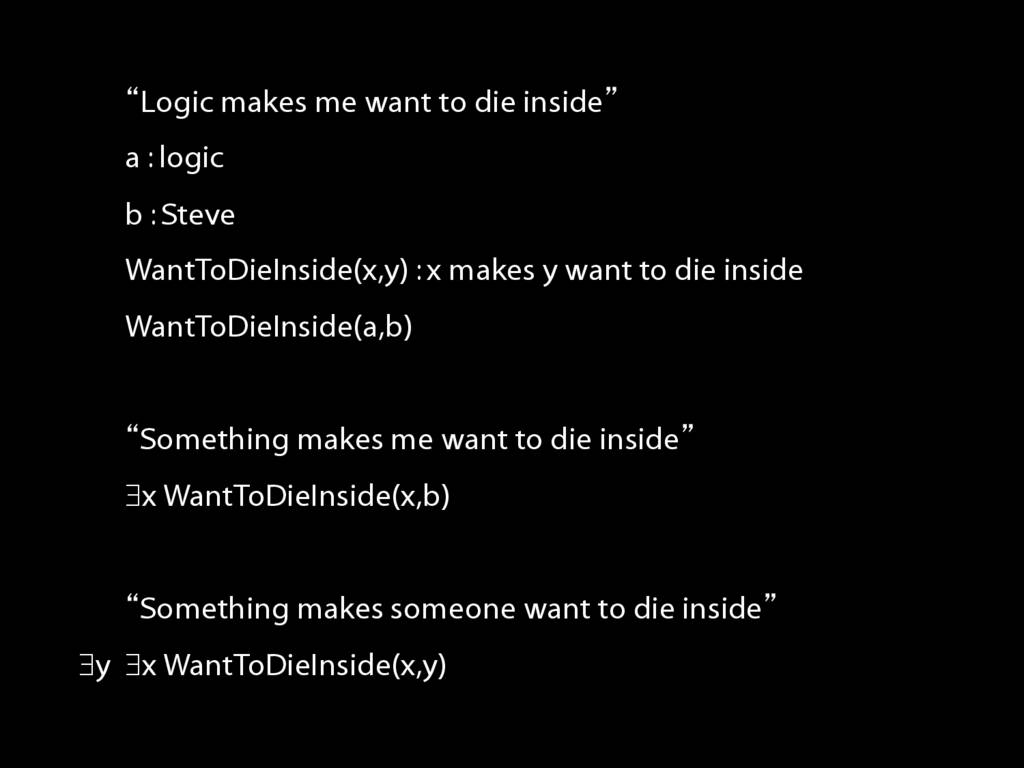

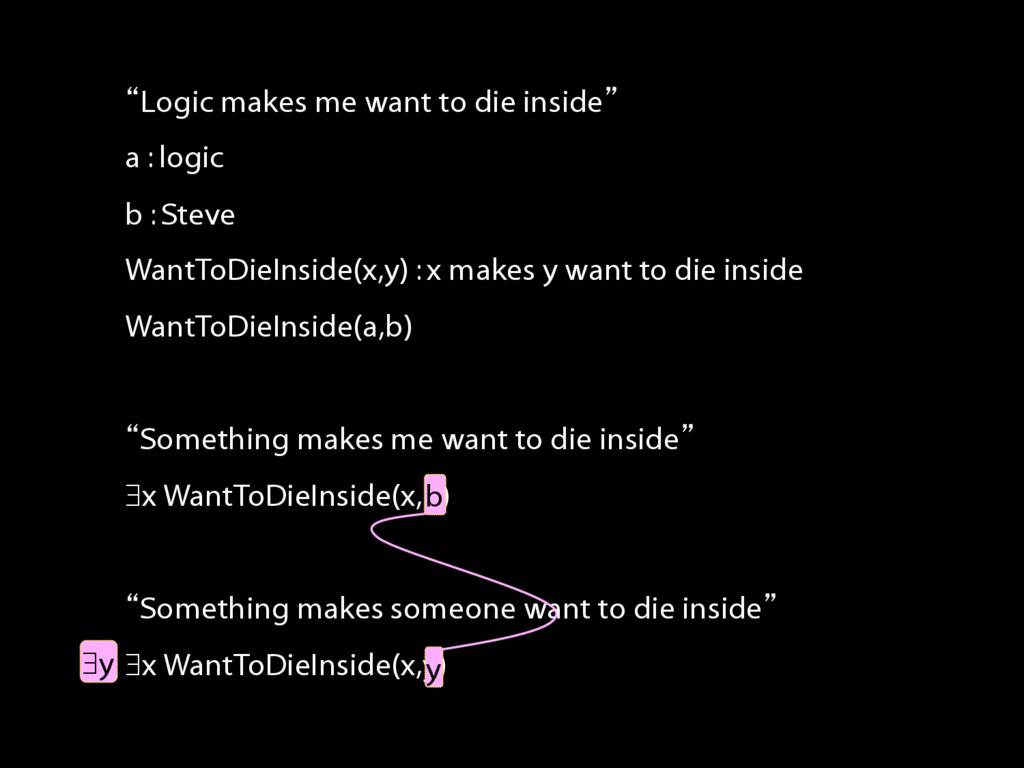

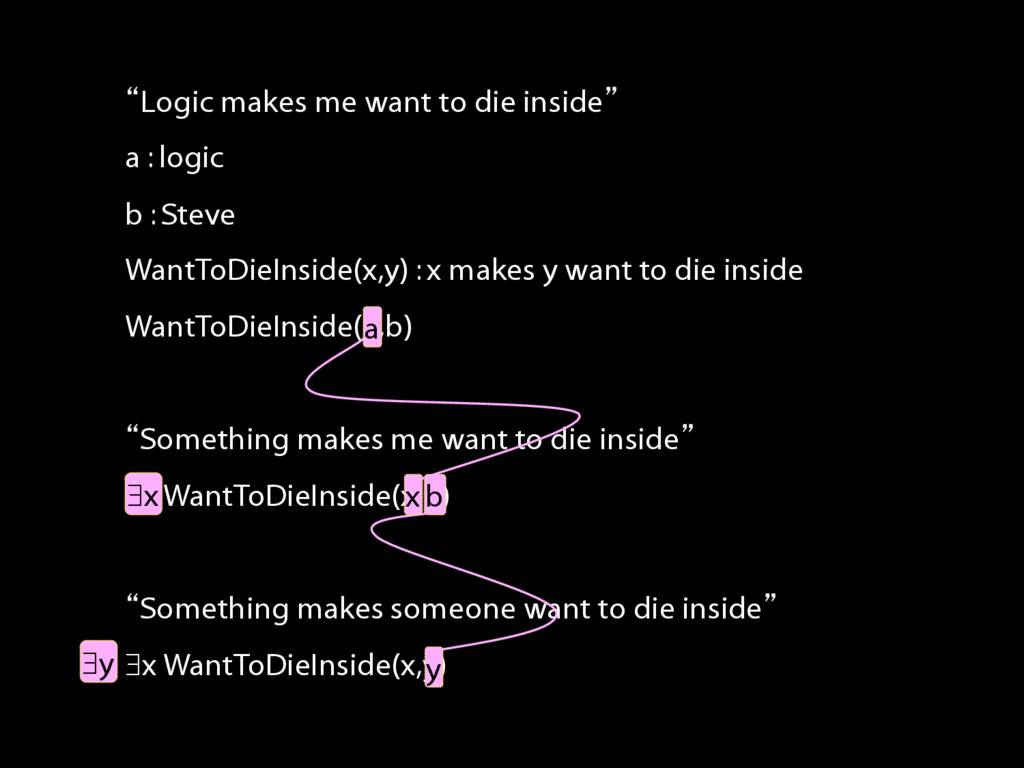

Multiple Quantifiers: Something Makes Someone Want to Die Inside

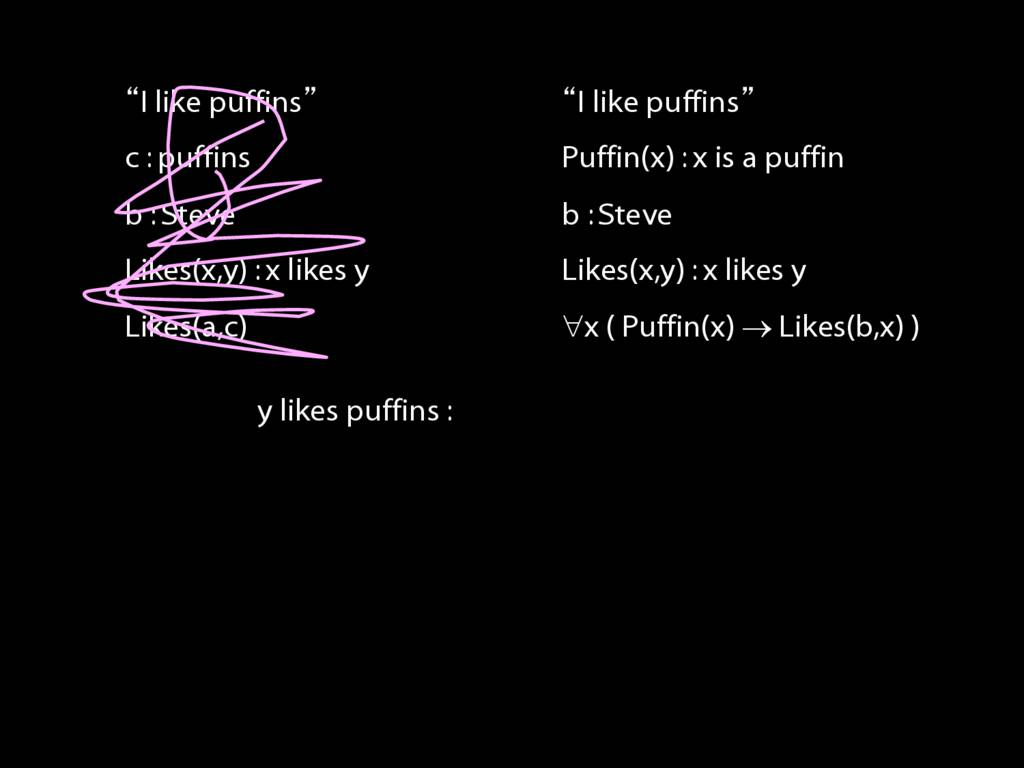

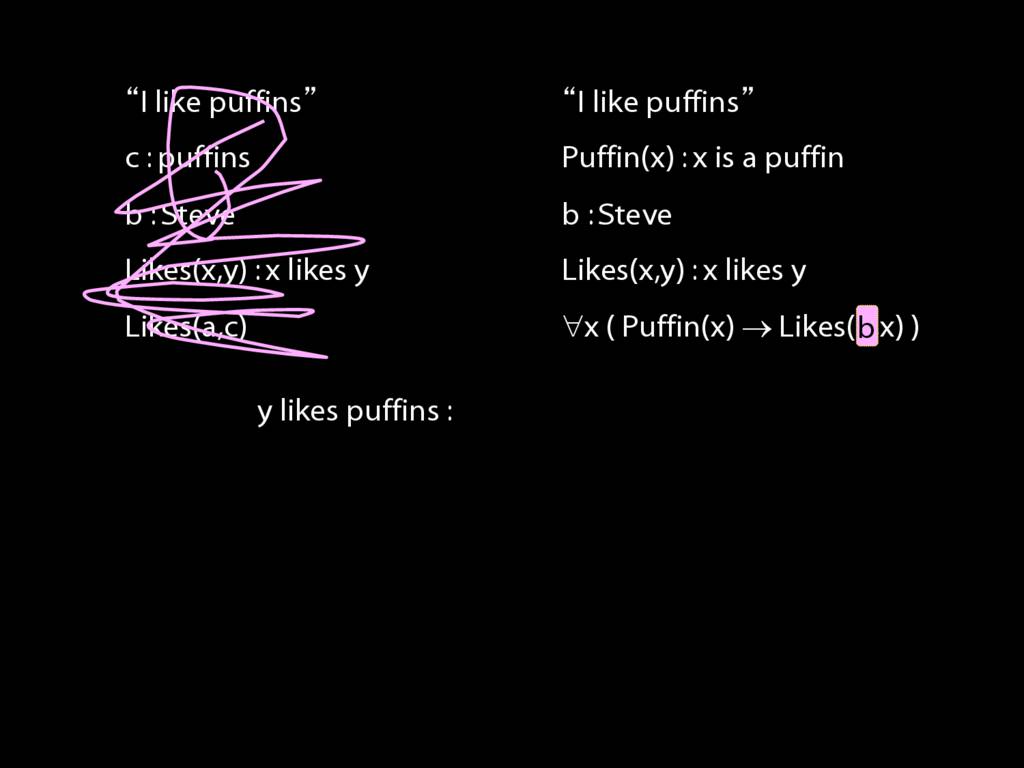

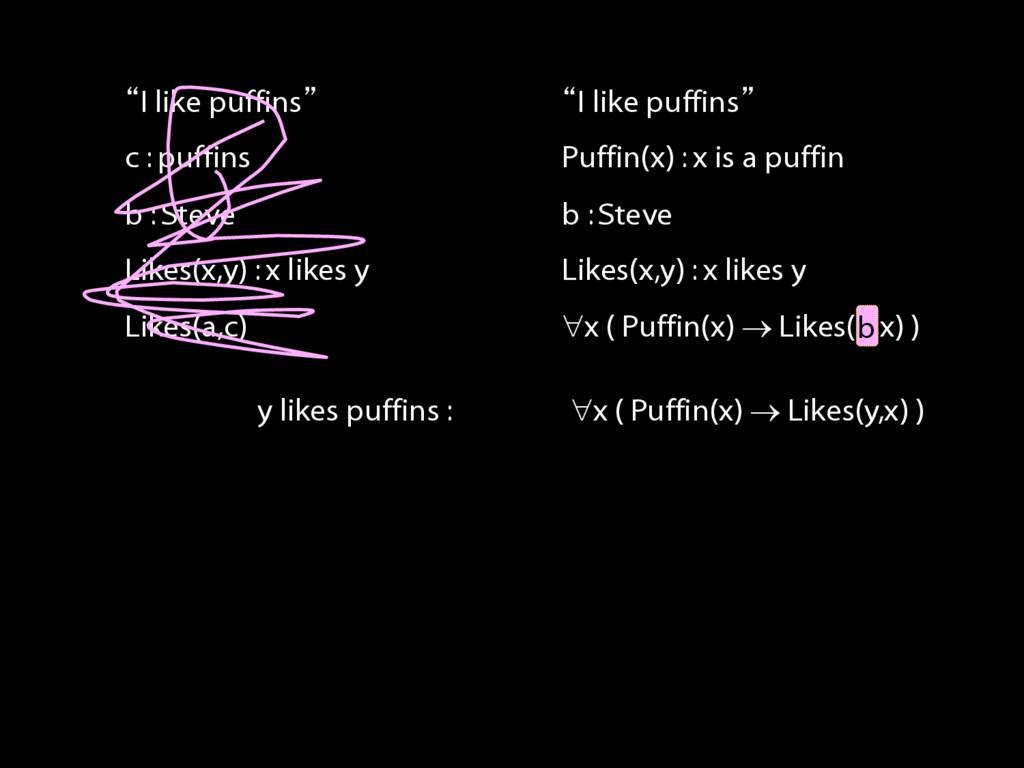

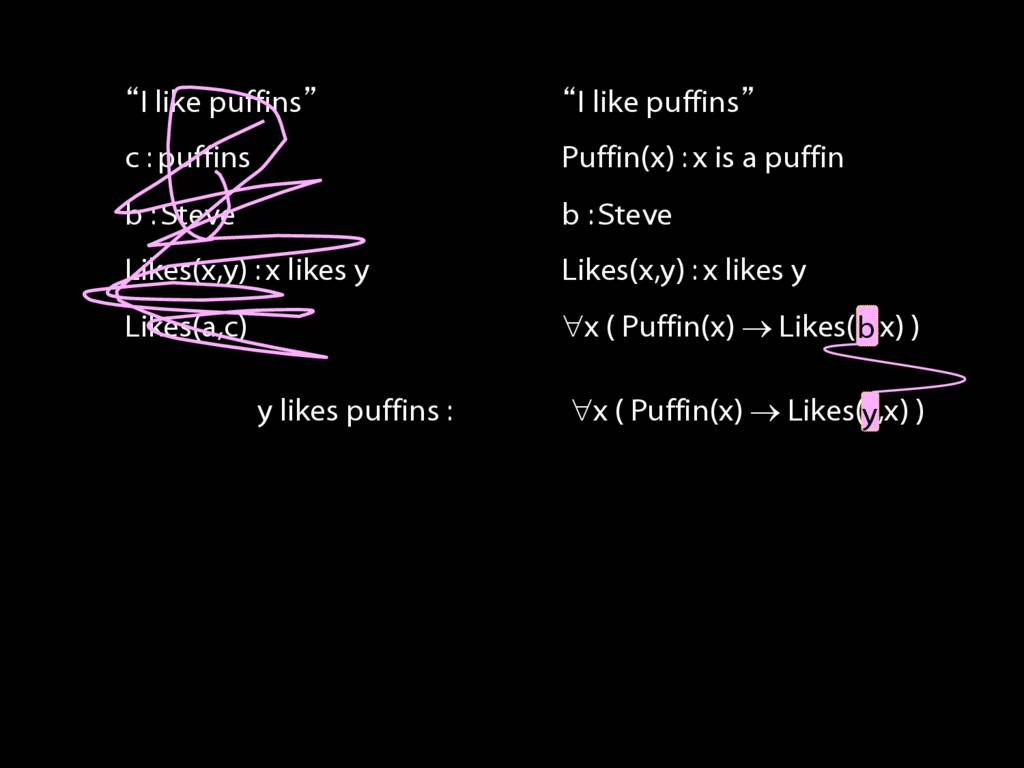

Multiple Quantifiers: Everyone Likes Puffins

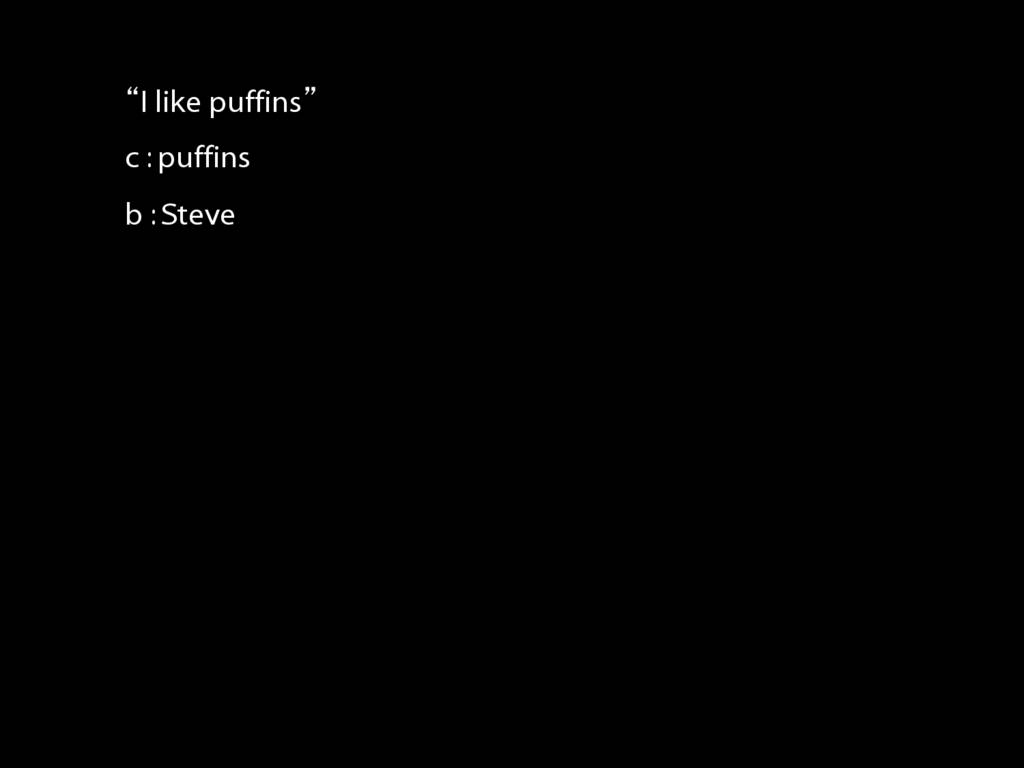

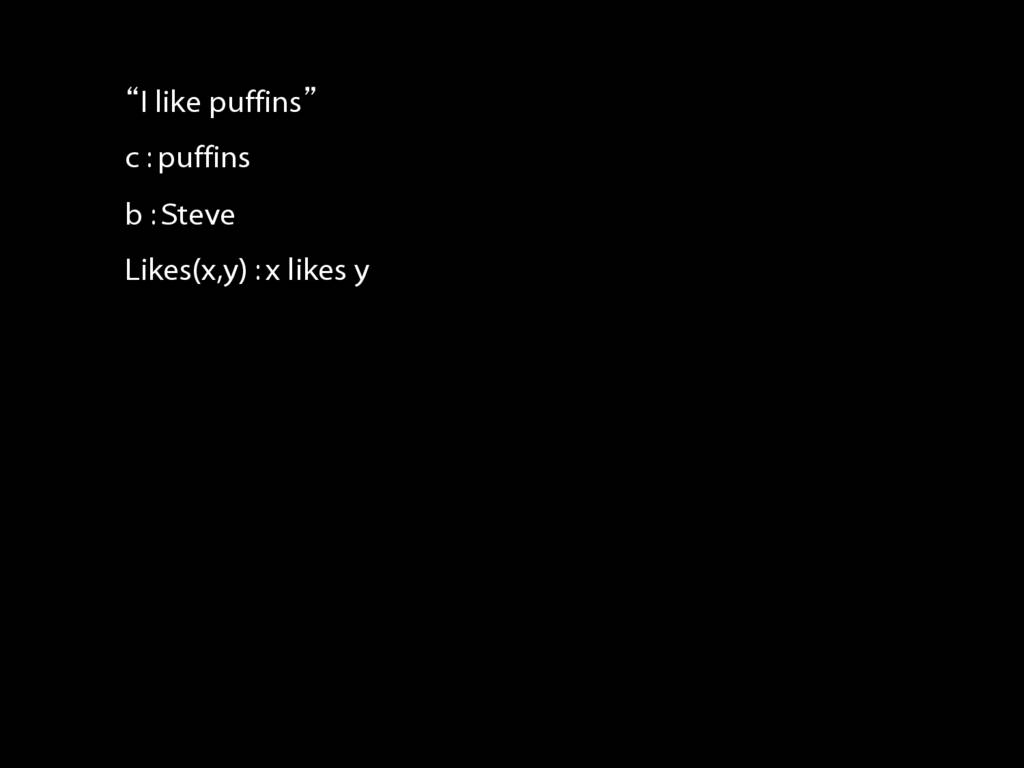

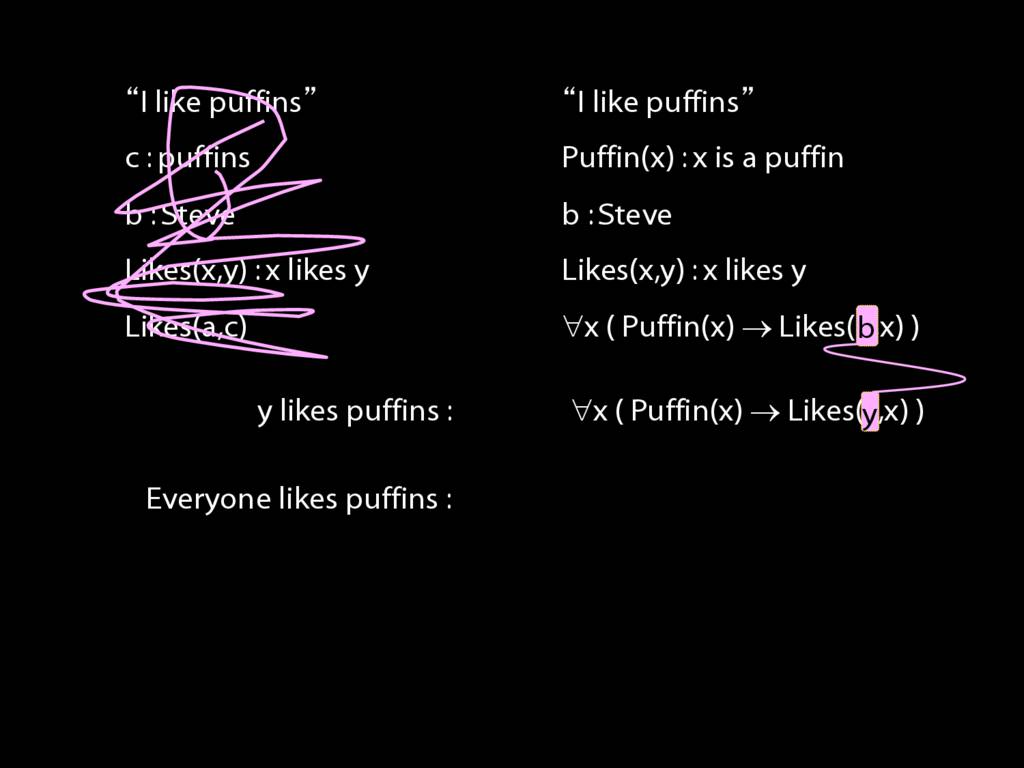

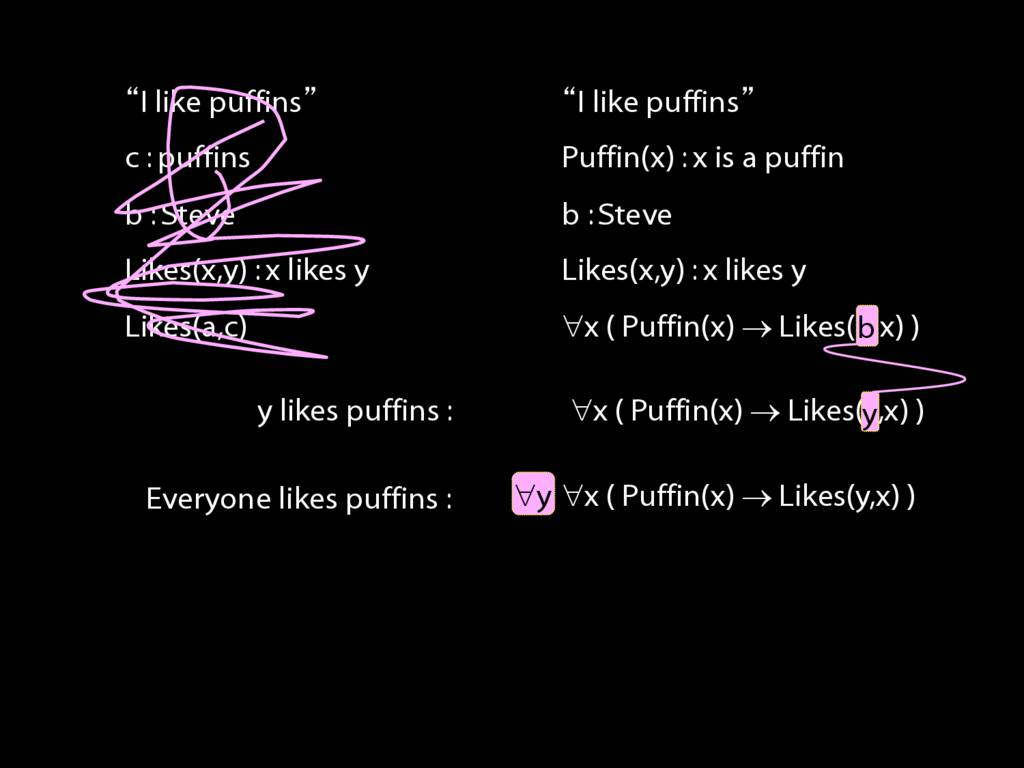

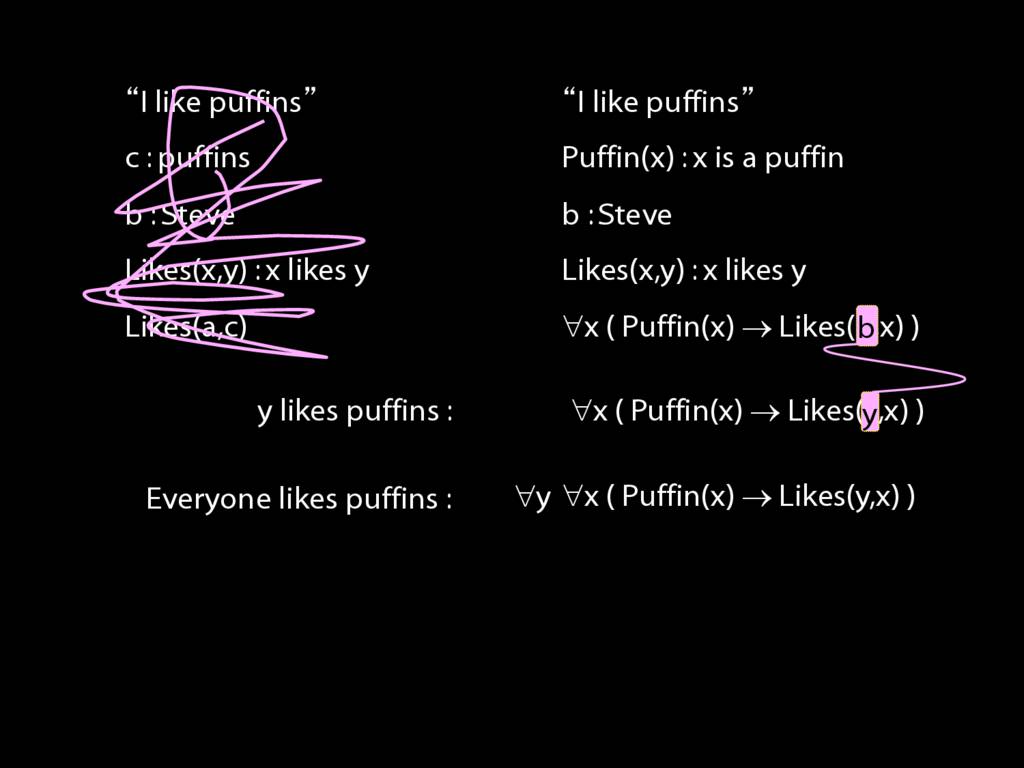

\section{Multiple Quantifiers: Everyone Likes Puffins}

\emph{Reading:} §11.1

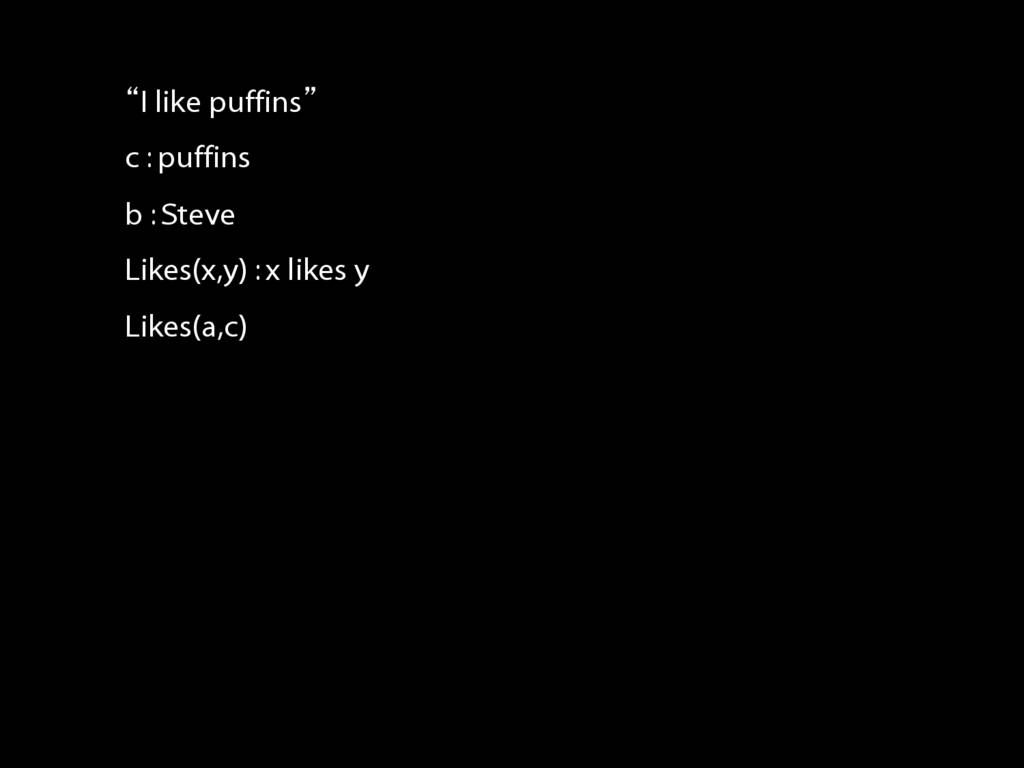

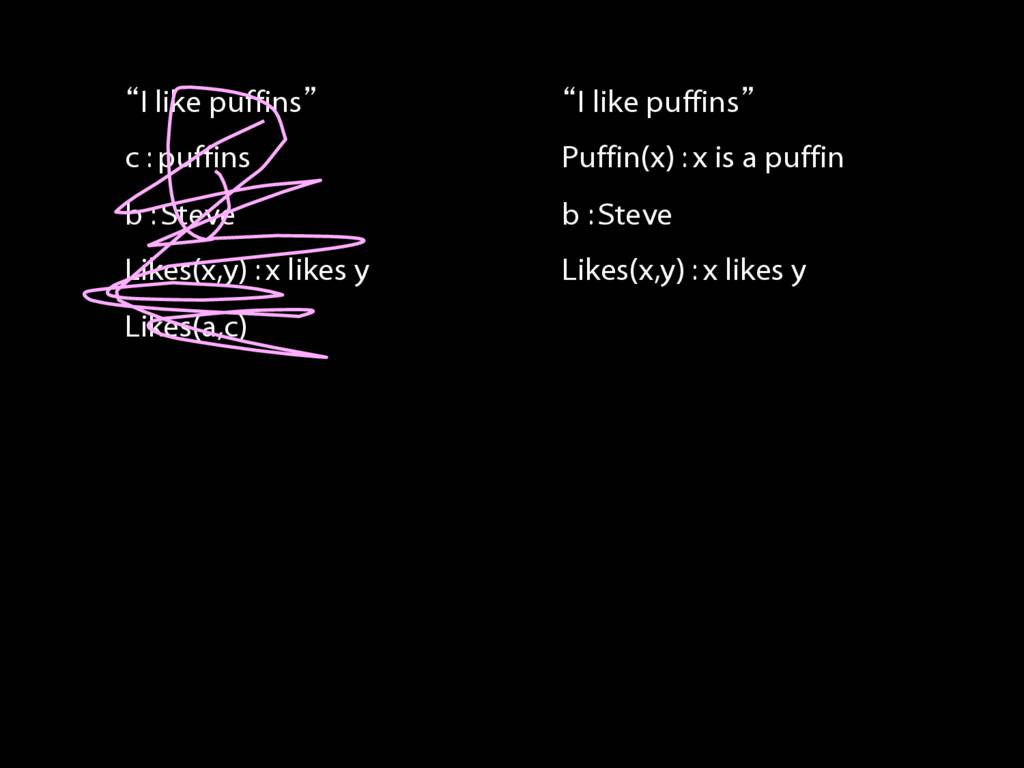

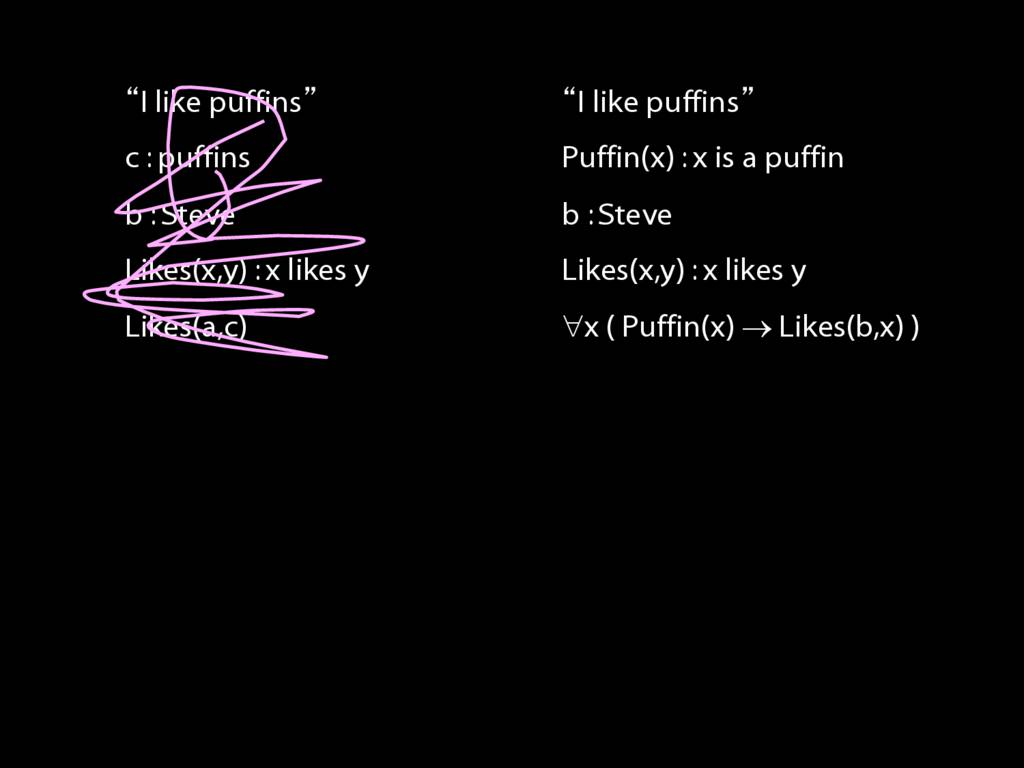

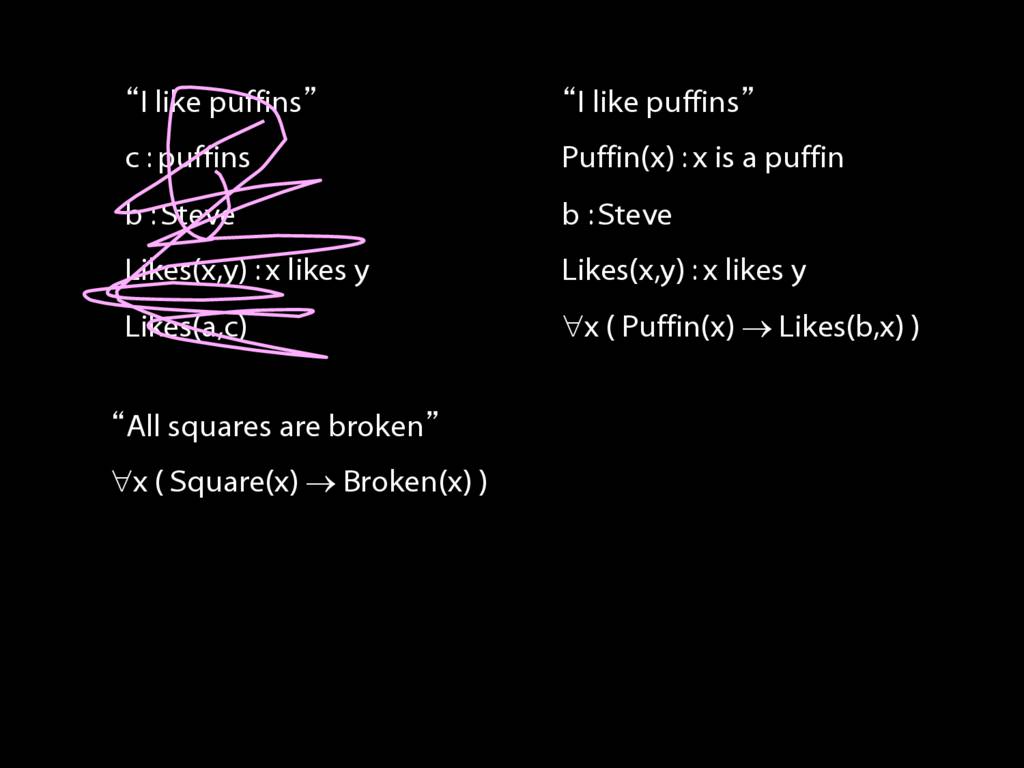

I like puffins:

\hspace{3mm} ∀x ( Puffin(x) → Likes(a,x) )

y likes puffins:

\hspace{3mm} ∀x ( Puffin(x) → Likes(y,x) )

Everyone likes puffins:

\hspace{3mm} ∀y ∀x ( Puffin(x) → Likes(y,x) )

11.2

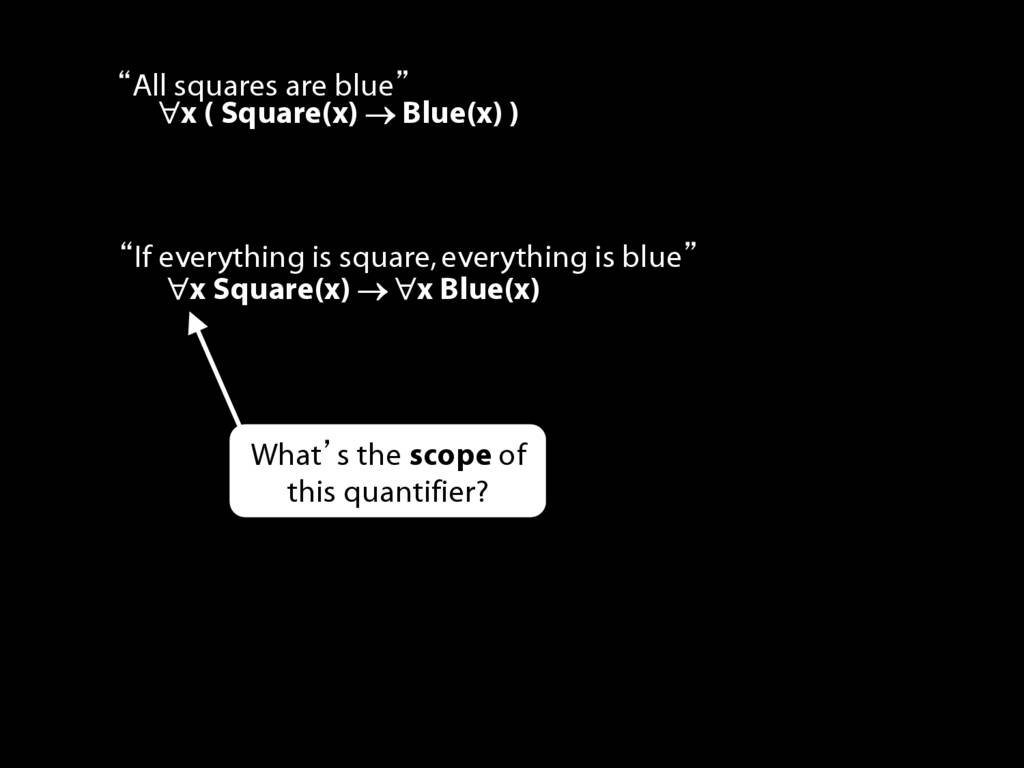

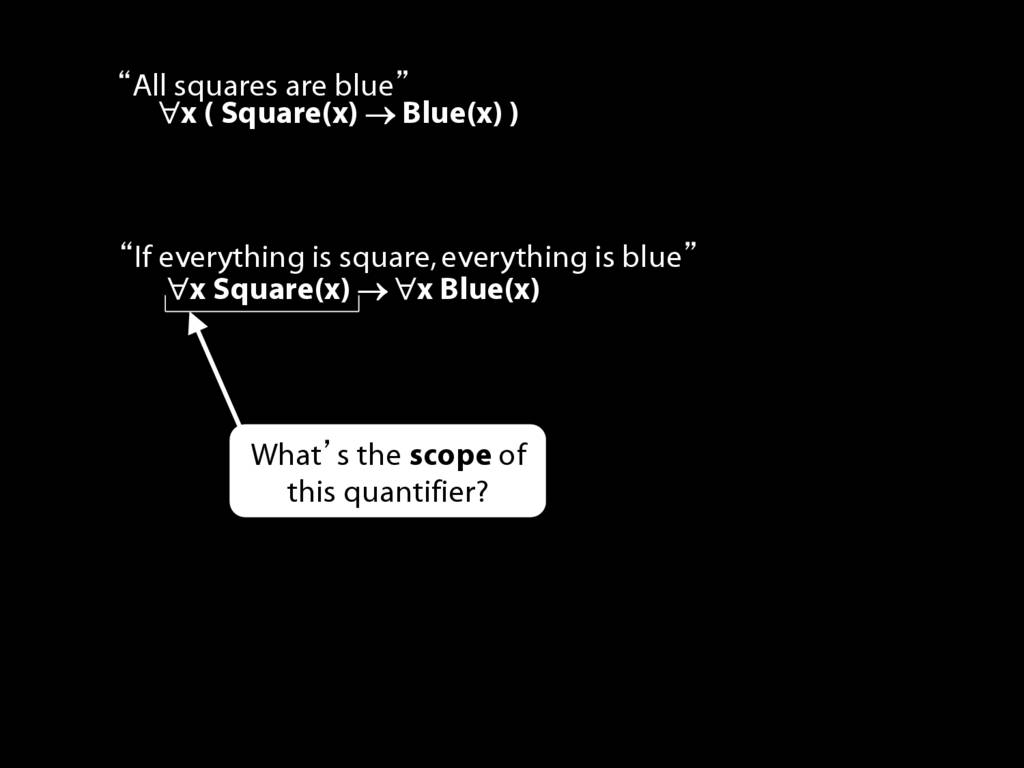

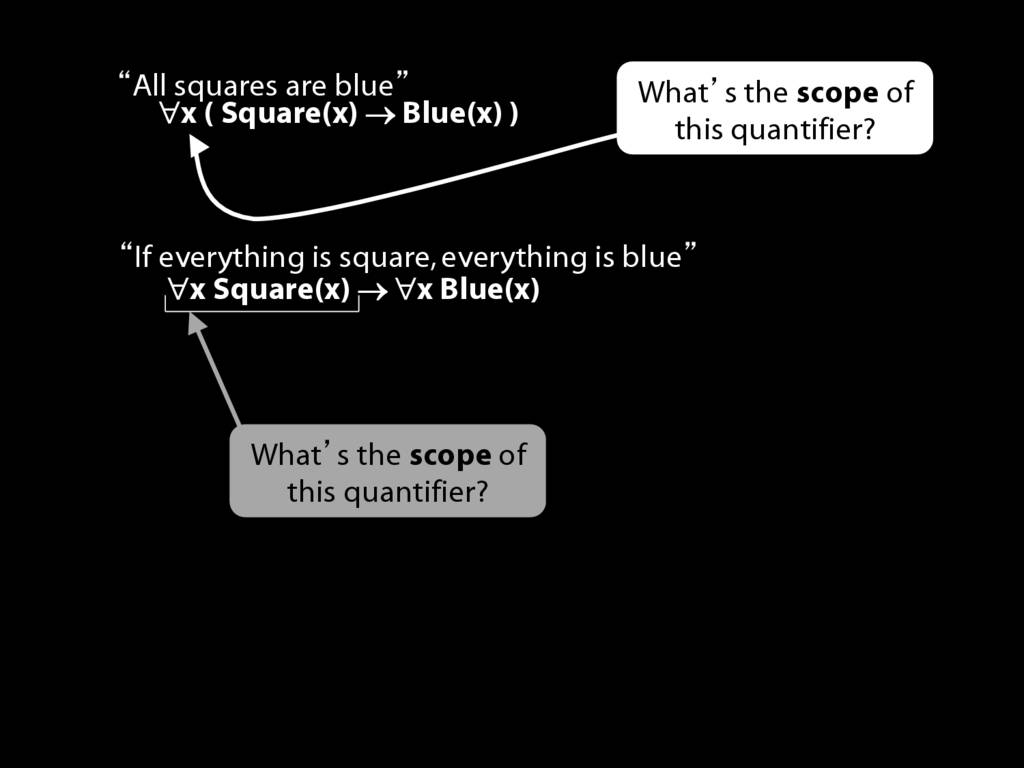

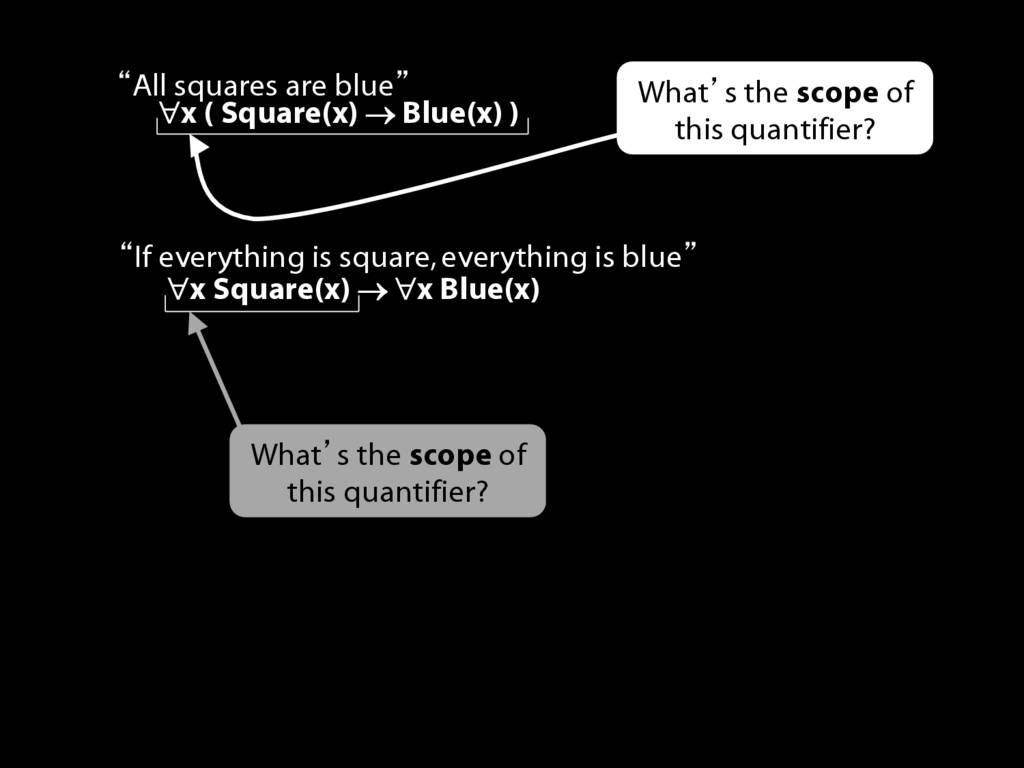

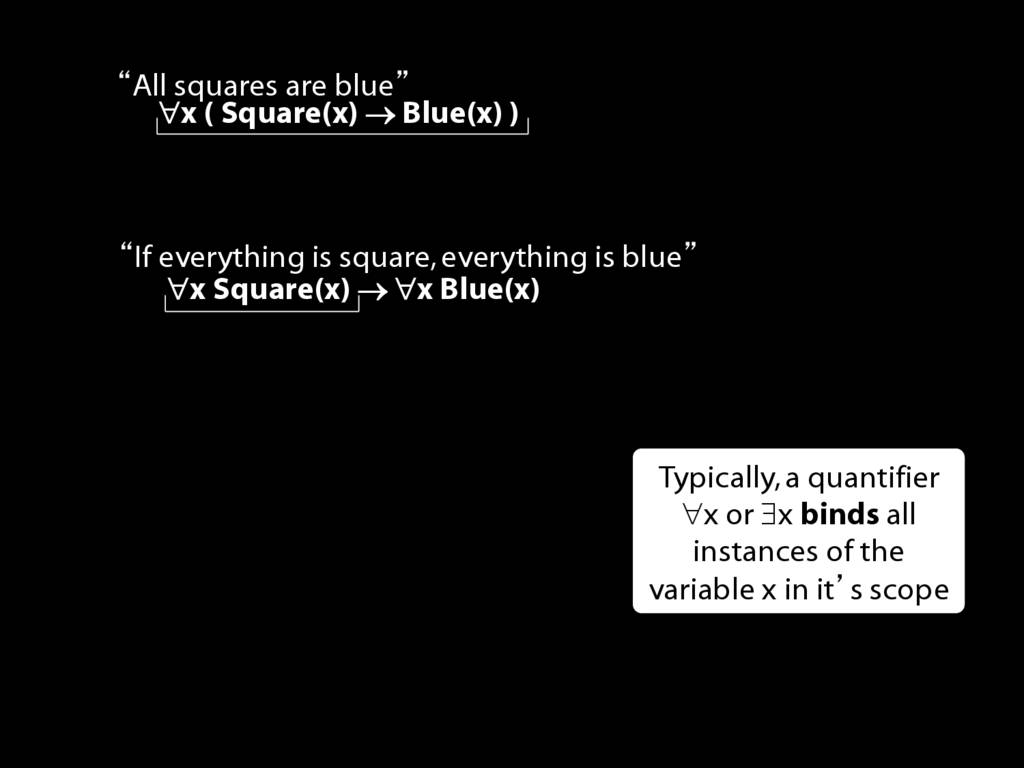

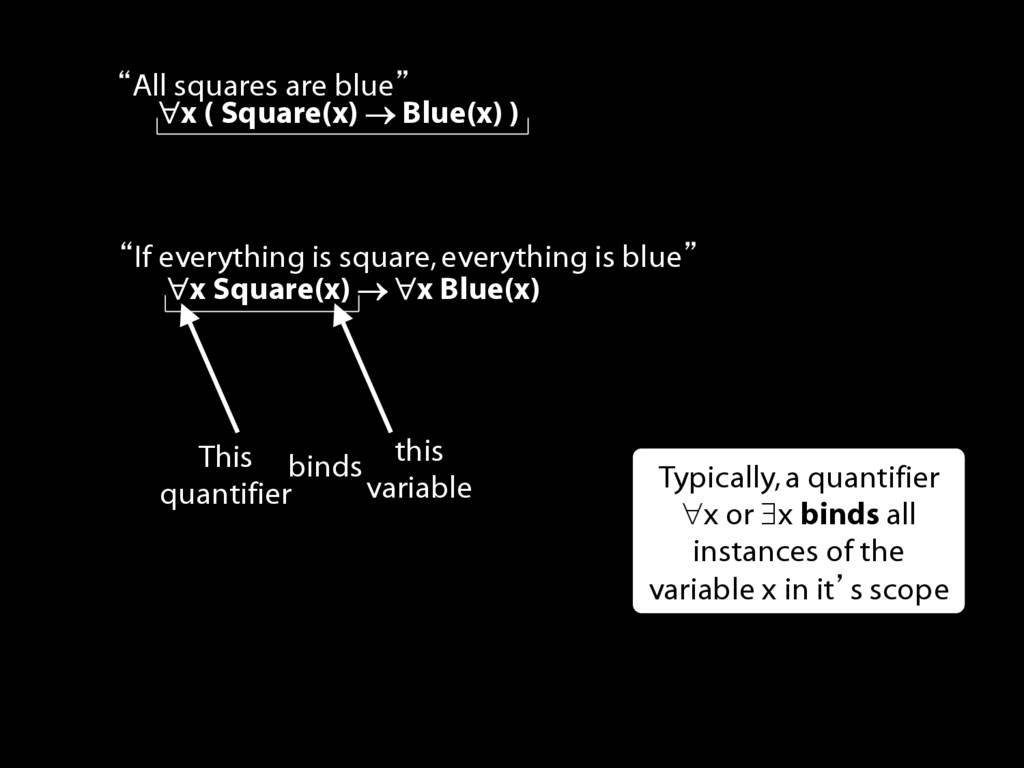

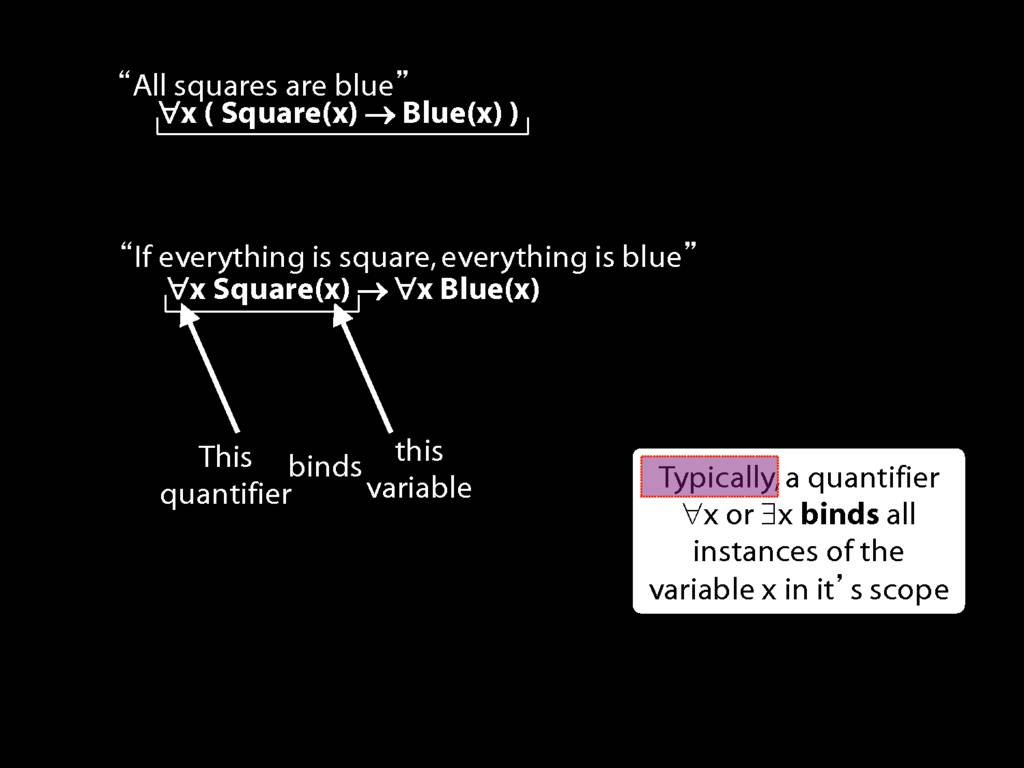

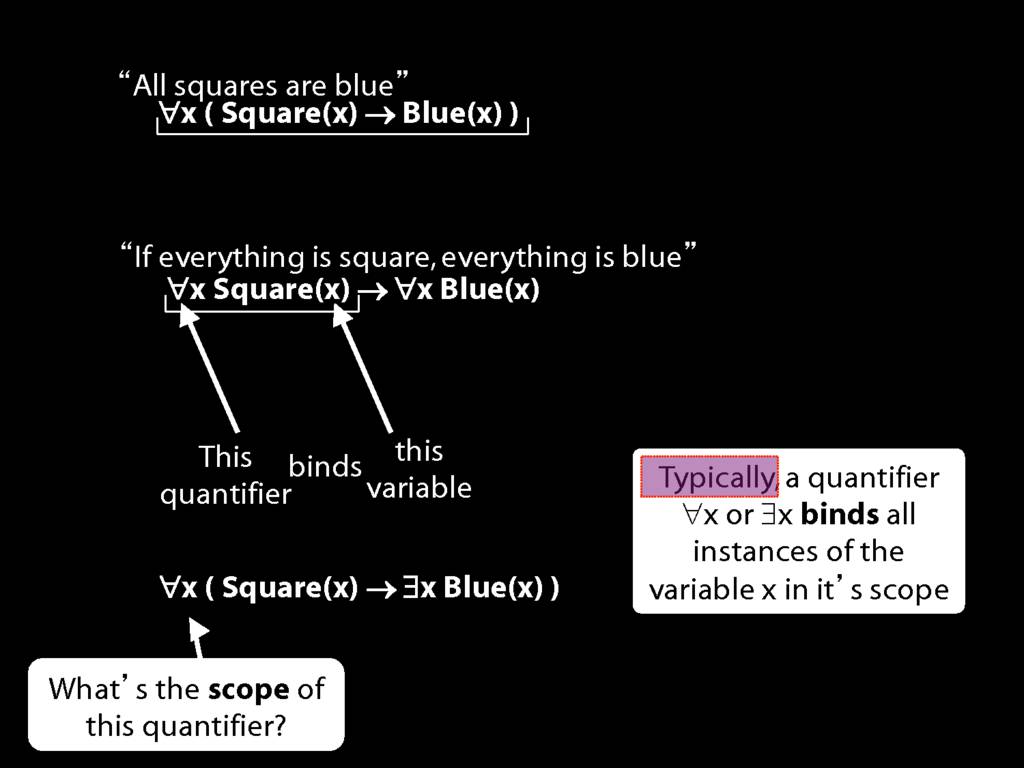

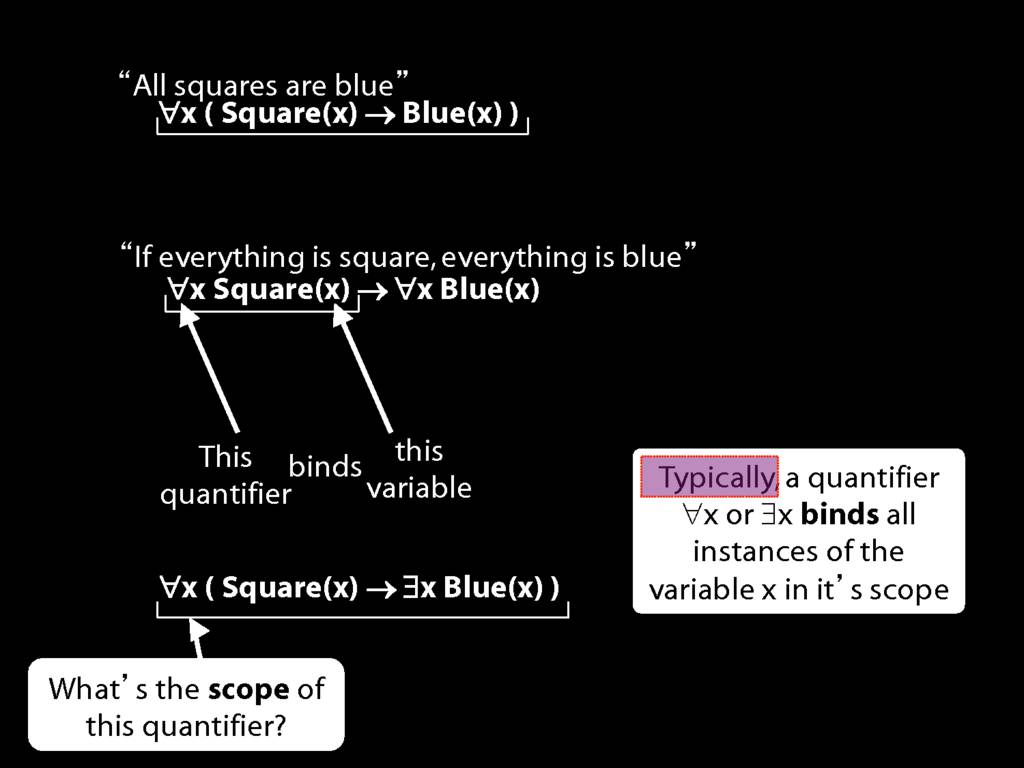

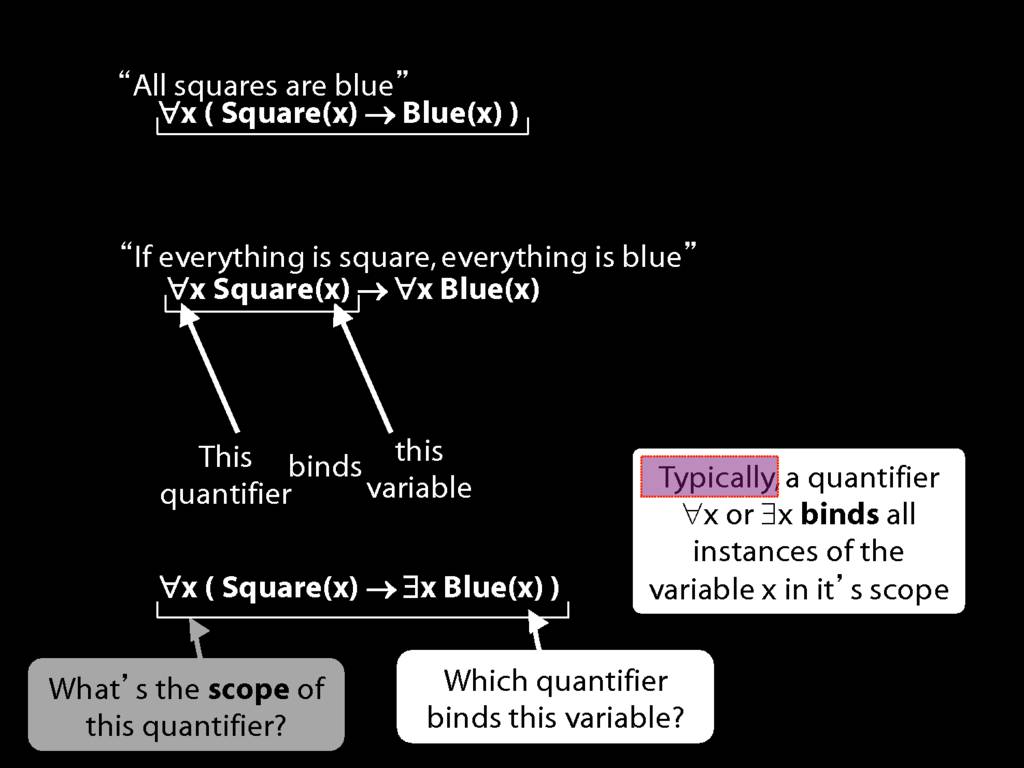

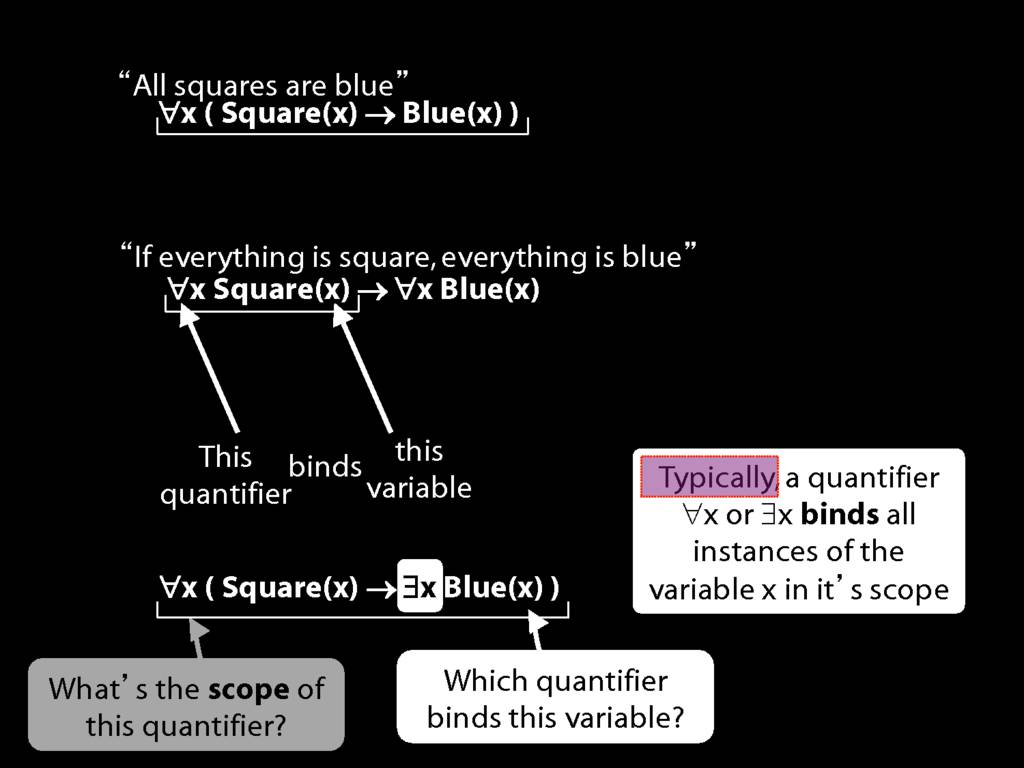

Quantifiers Bind Variables

\section{Quantifiers Bind Variables}

\emph{Reading:} §9.3

Suppose you had to work out whether this sentence is true in a certain possible situation.

That would be tricky given what we've said so far about the meanings of the quantifiers.

It would be tricky because we have talked about replacing variables with names without saying, in cases like this, which variables to replace.

To specify this we need the notion of binding ...

∀x( Square(x) → ∃x Blue(x) )

But first, to see the problem, think about this variable instance.

When do we replace it? Is it when removing the truth of the universal quantifier?

Or should we leave the variable in tact and replace it when removing the existential quantifier?

To answer this question we need the notion of binding ...

(Btw, this sentence is eqvuivalent to 'either not everything is square or something is blue')

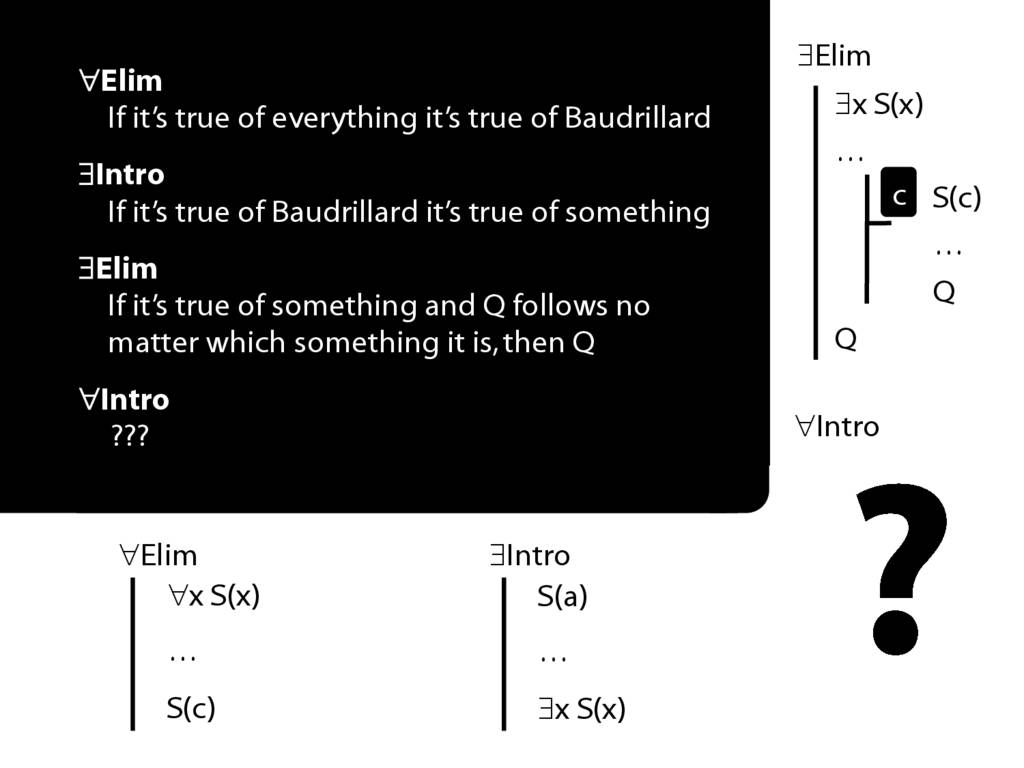

Summary of Quantifier Rules So Far

\section{Summary of Quantifier Rules So Far}

\emph{Reading:} §12.1, §12.2, §12.3, §13.1, §13.2

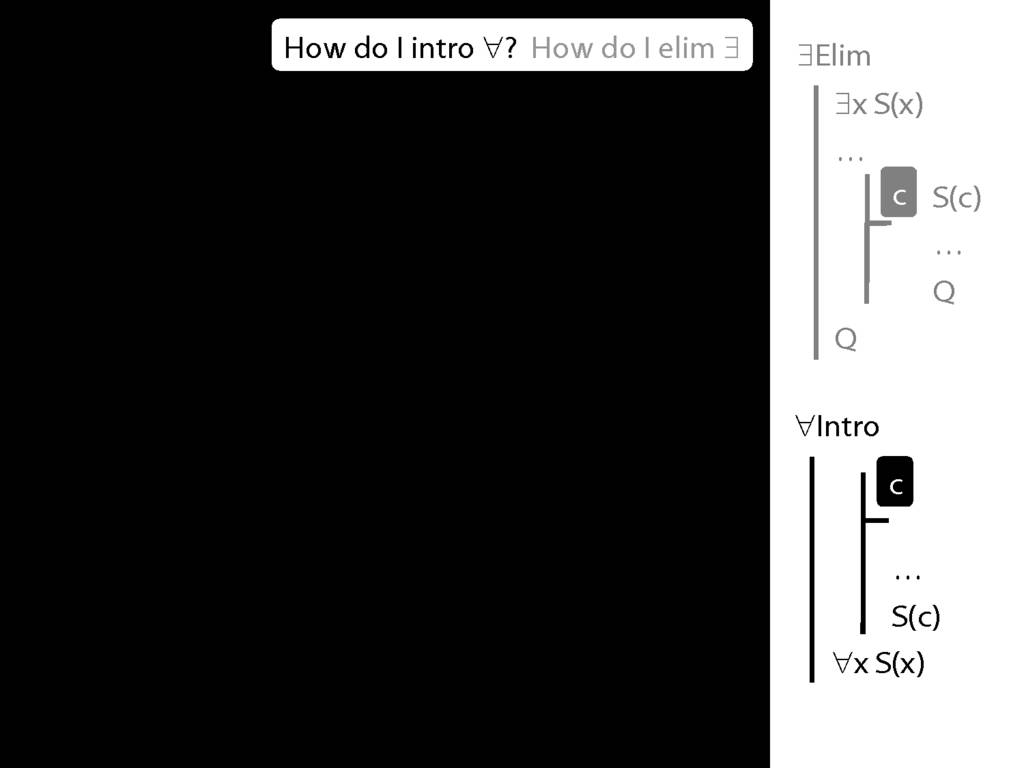

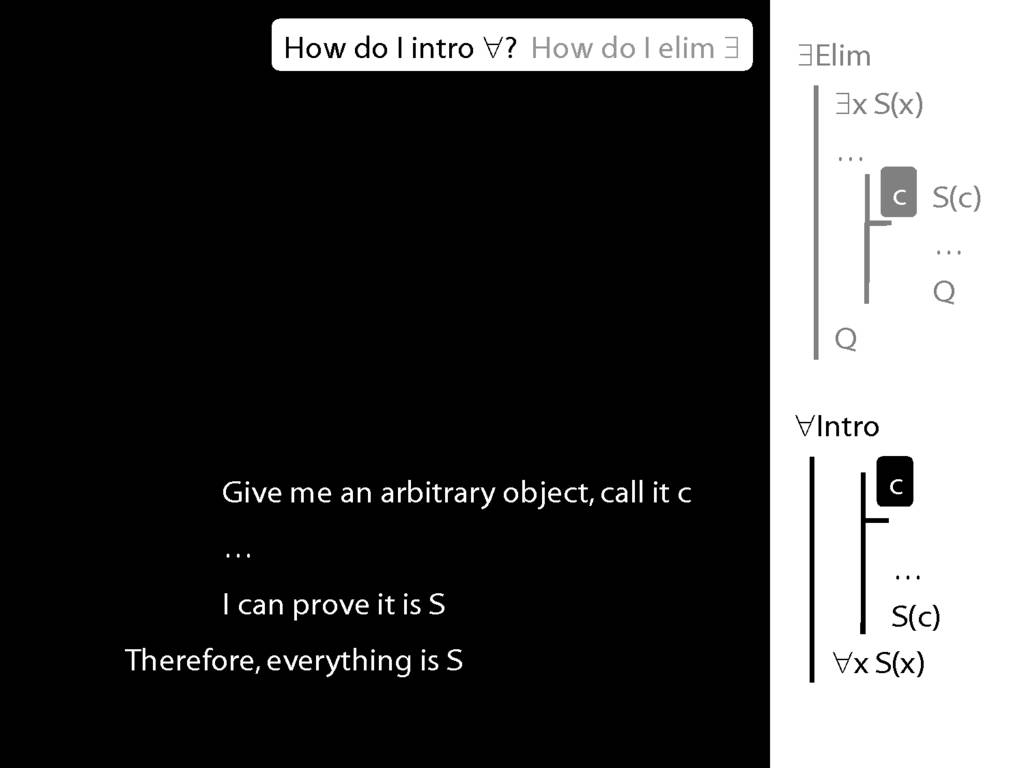

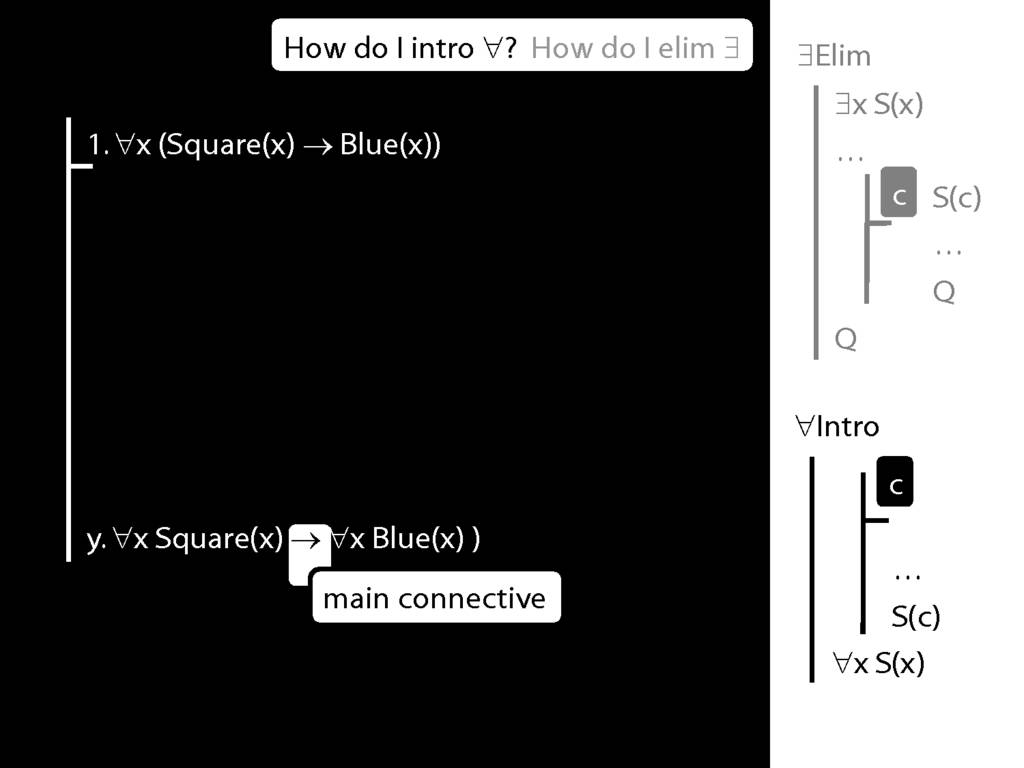

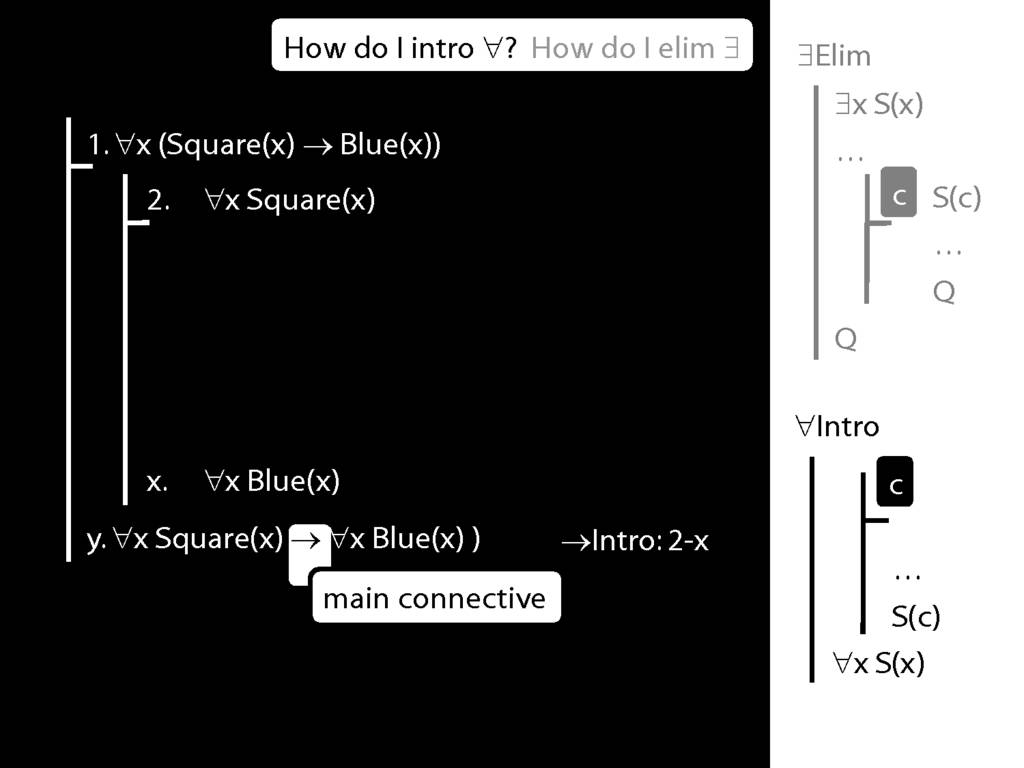

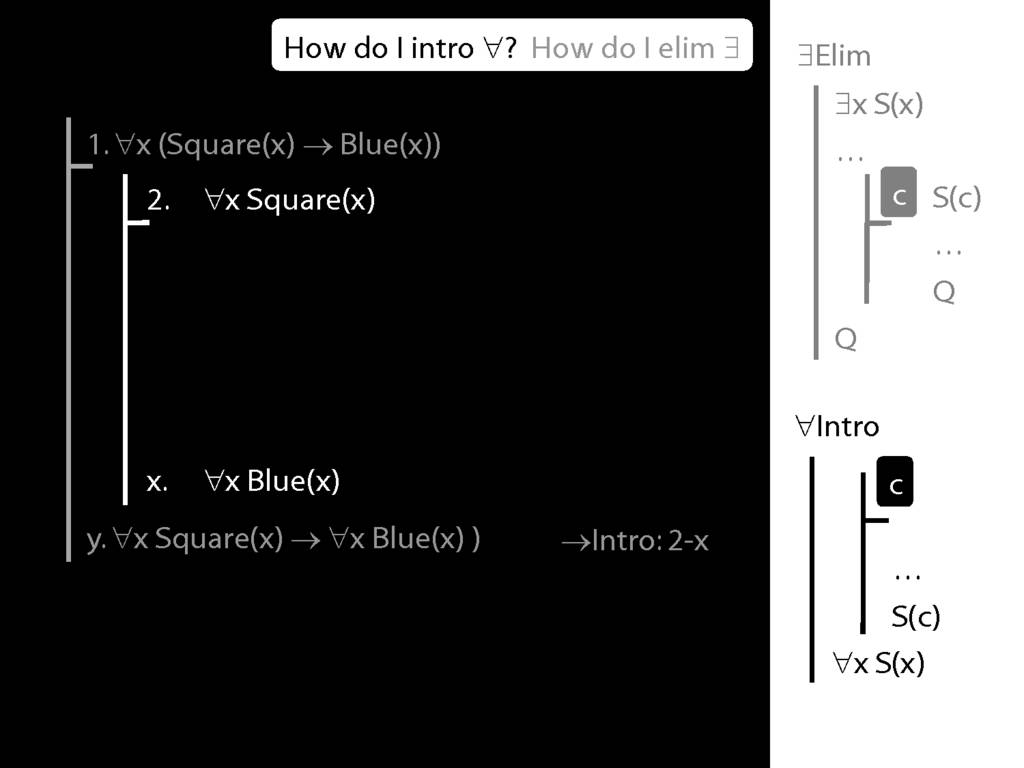

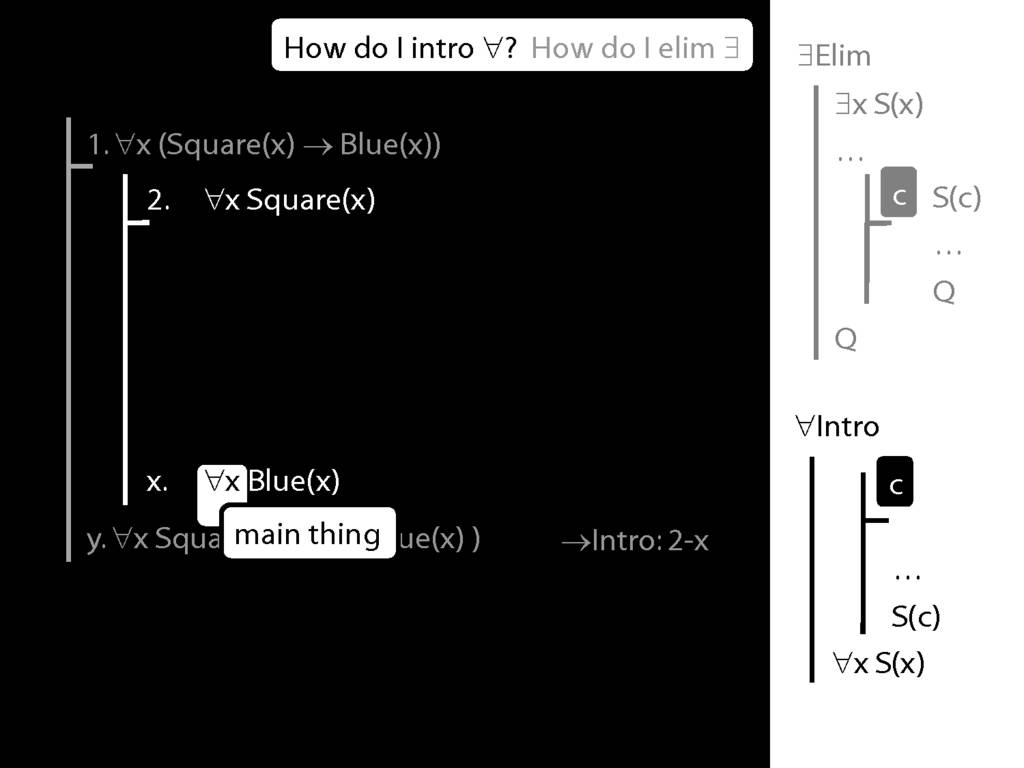

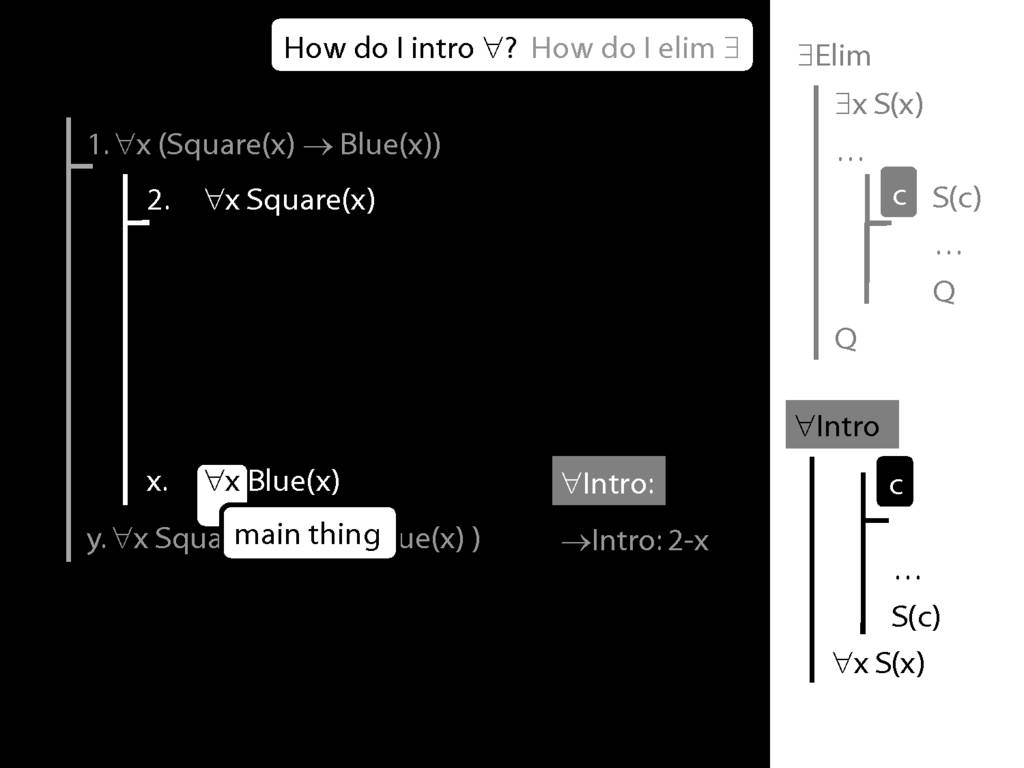

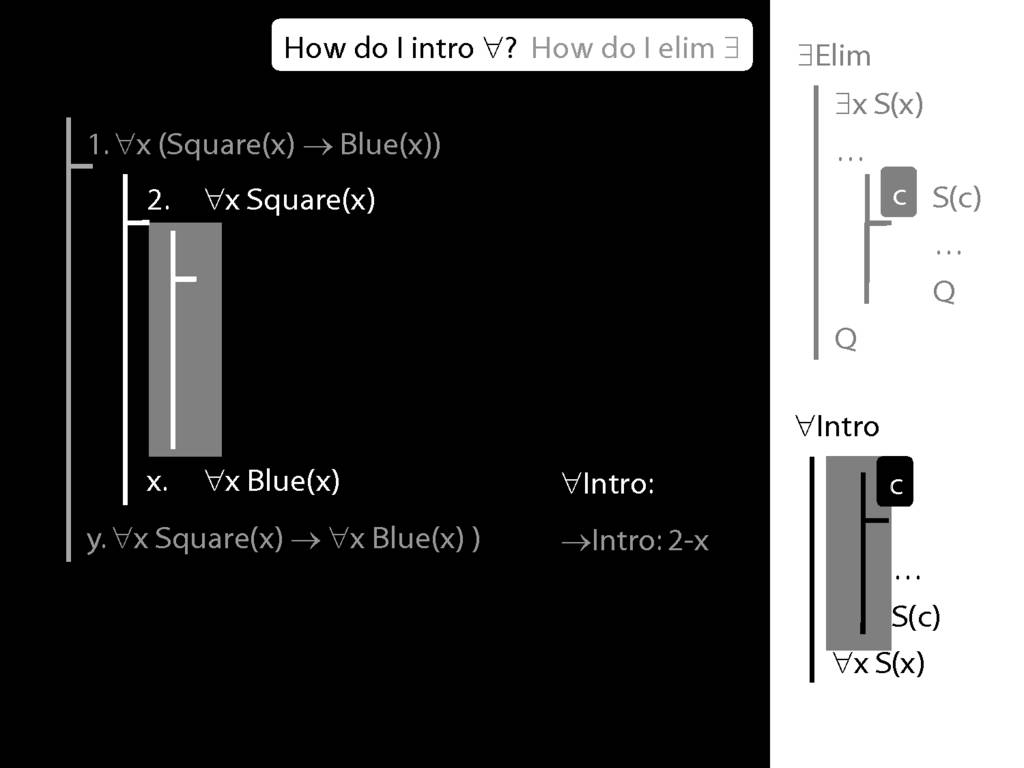

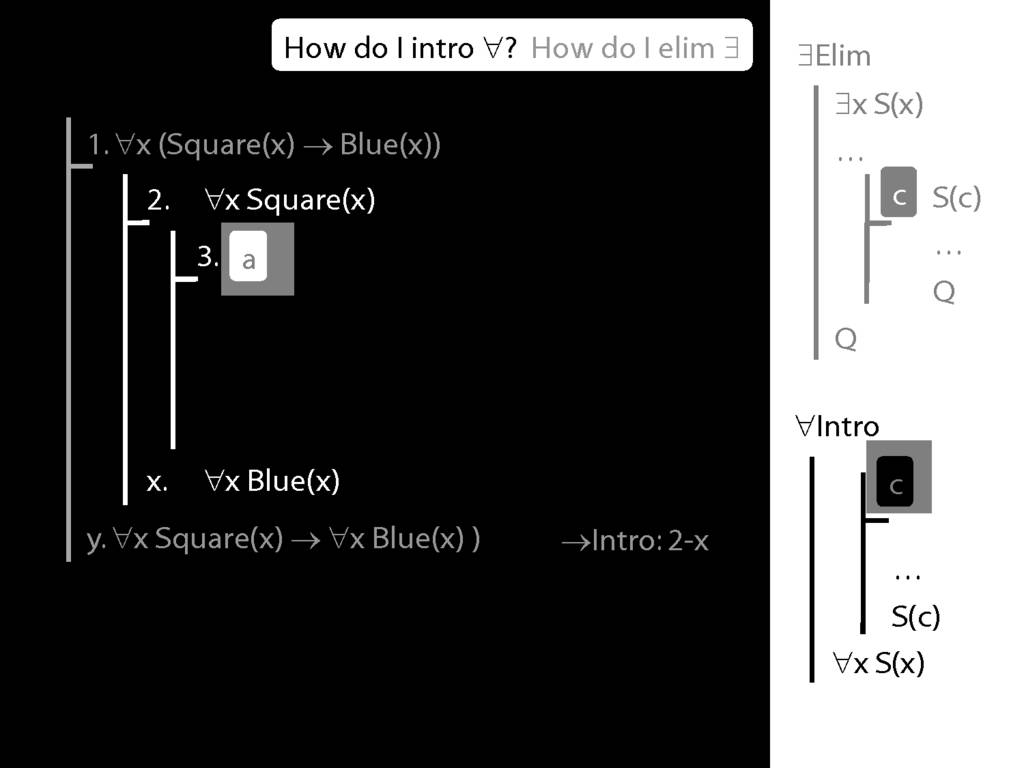

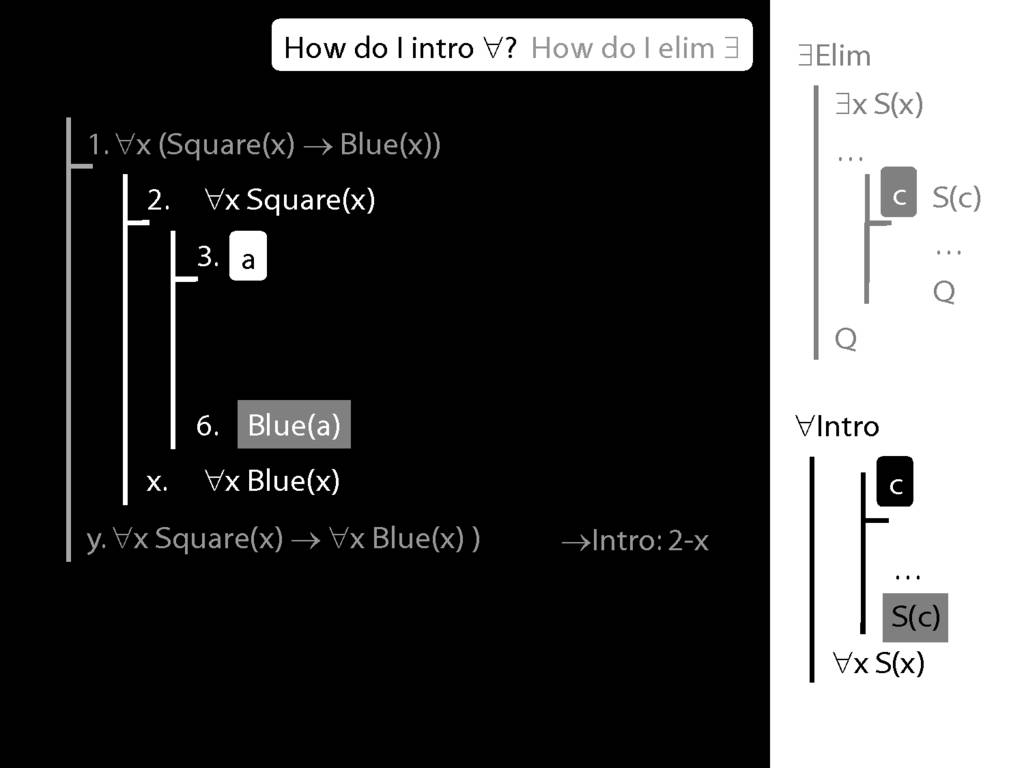

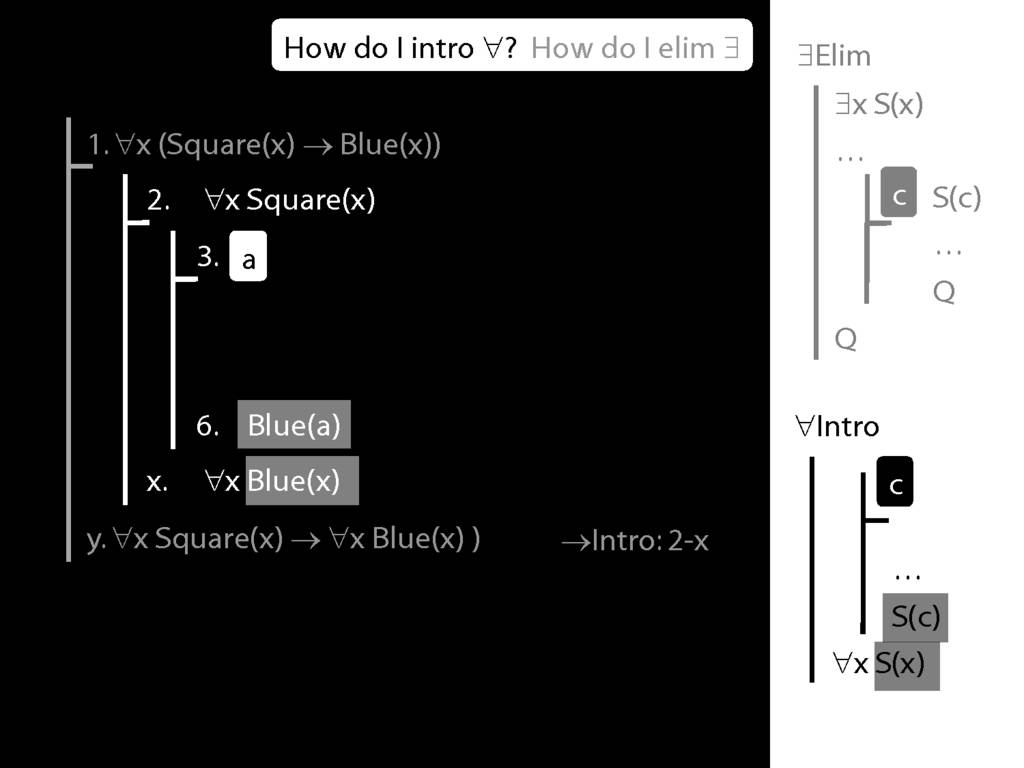

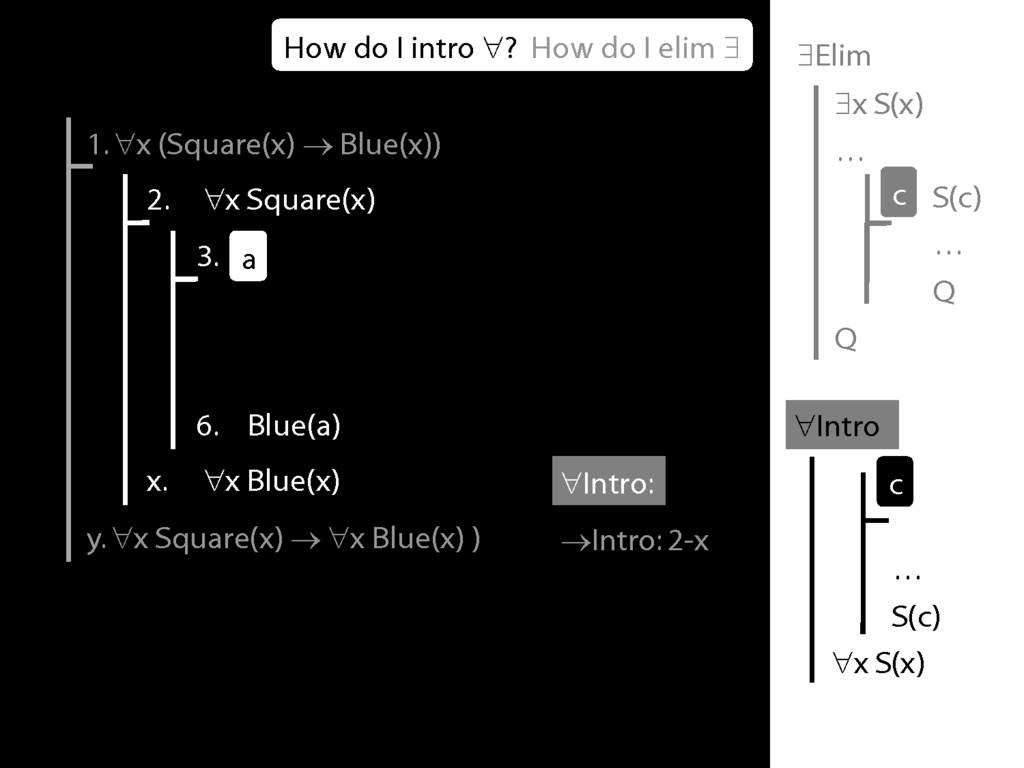

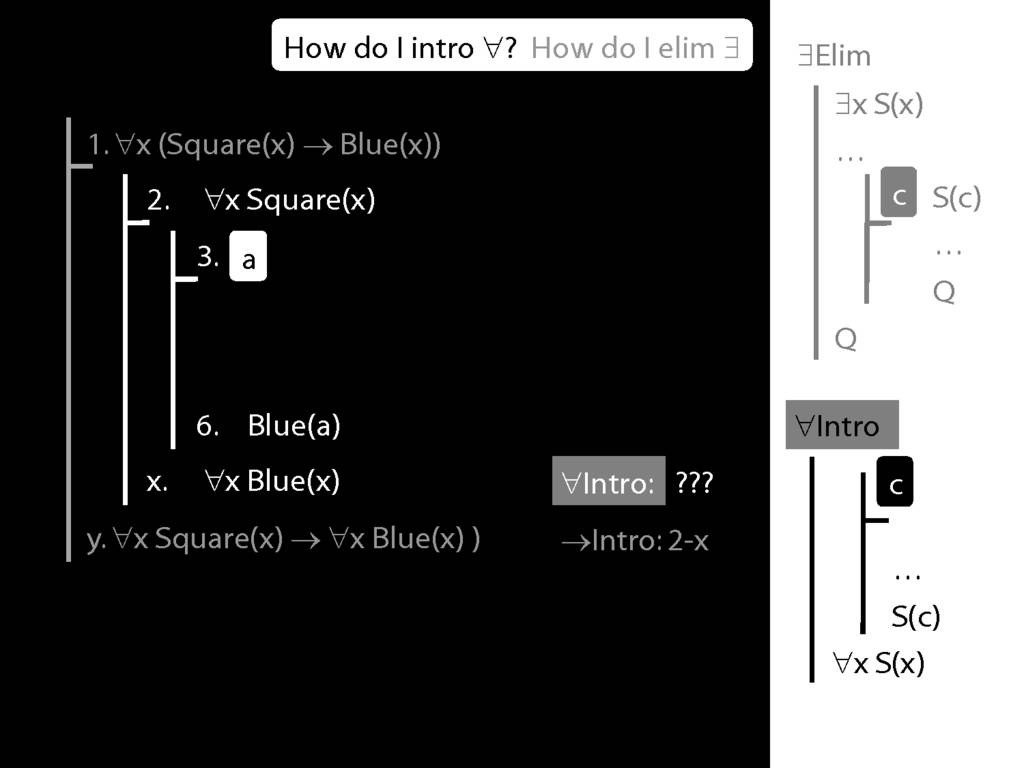

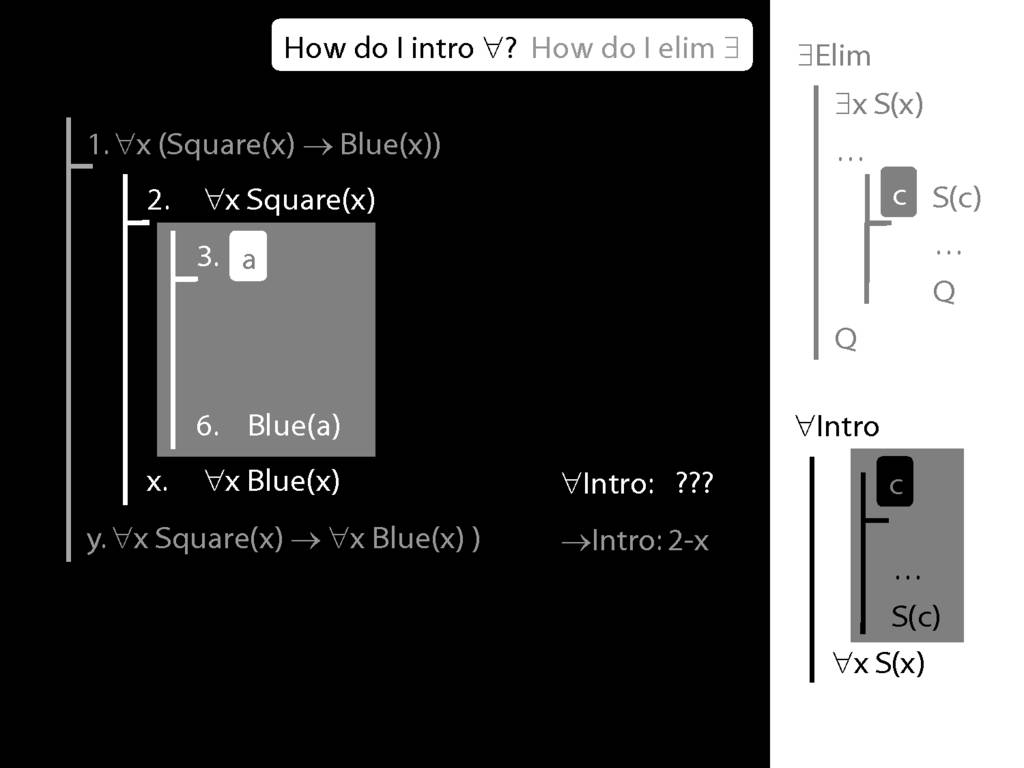

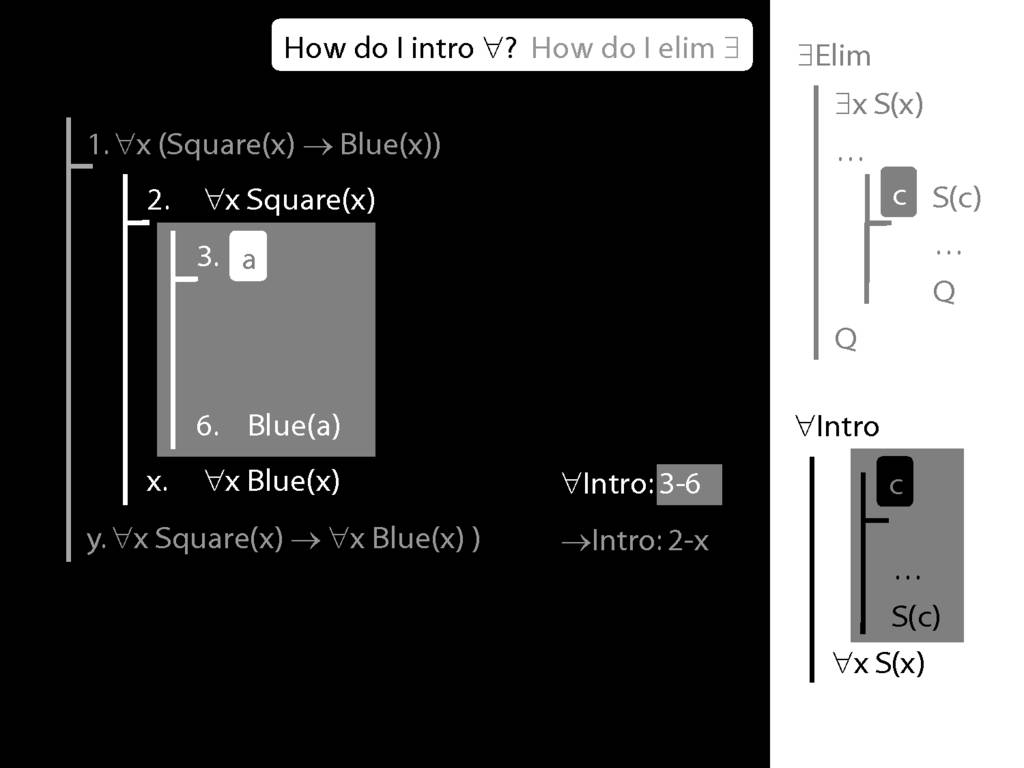

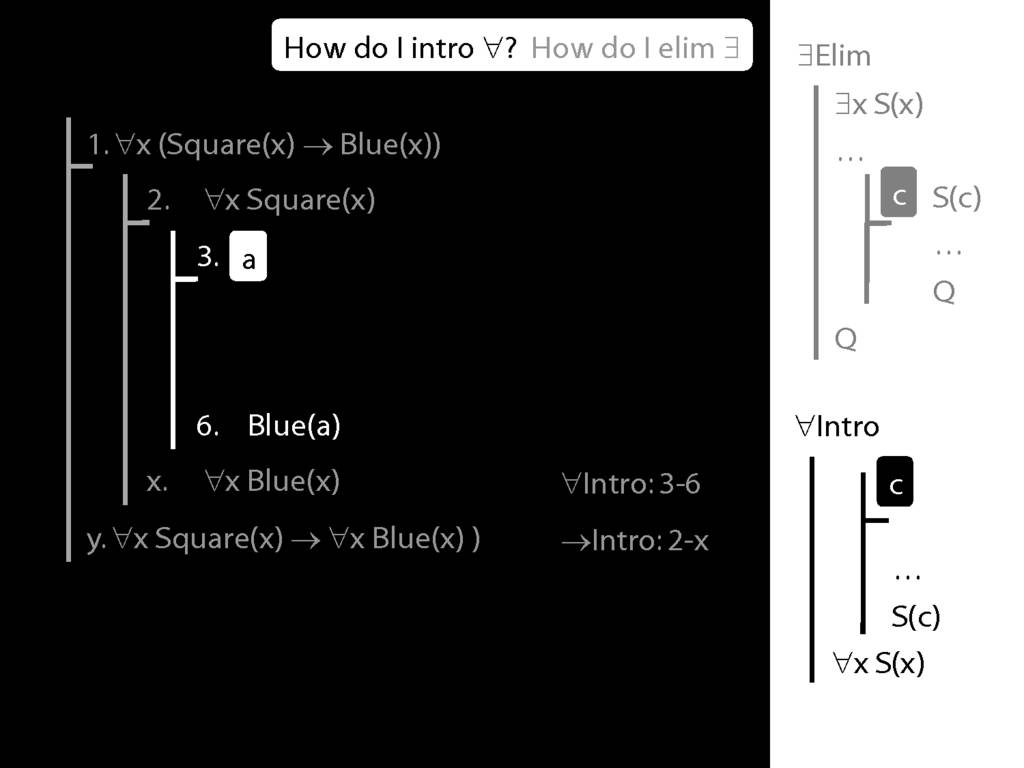

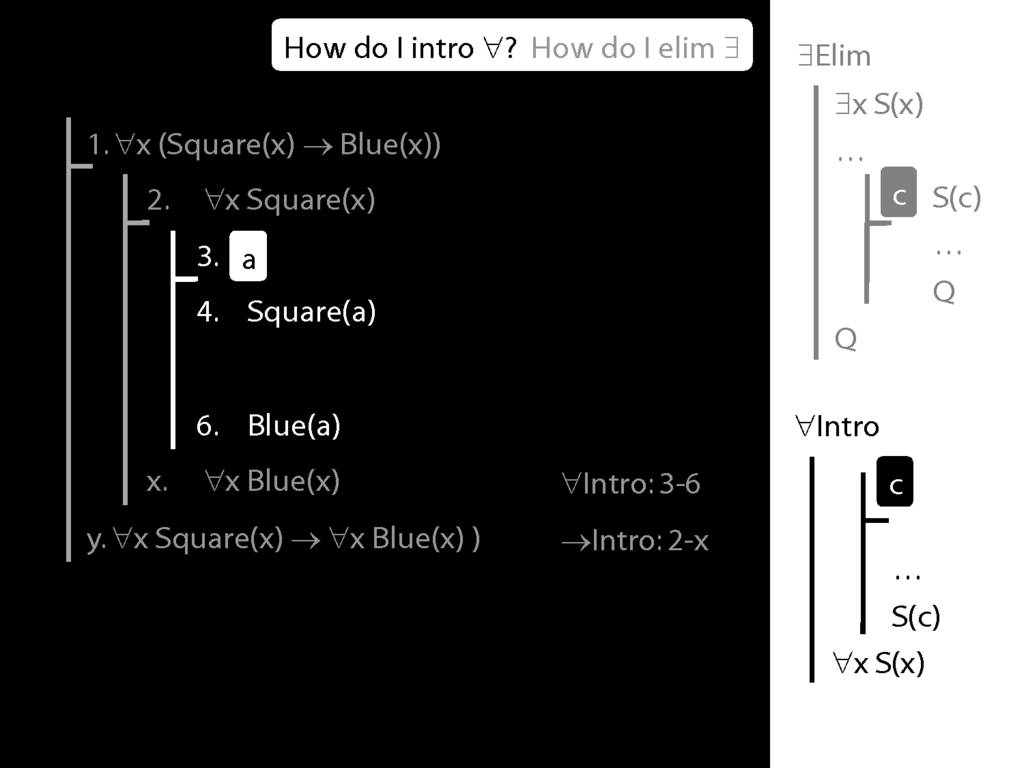

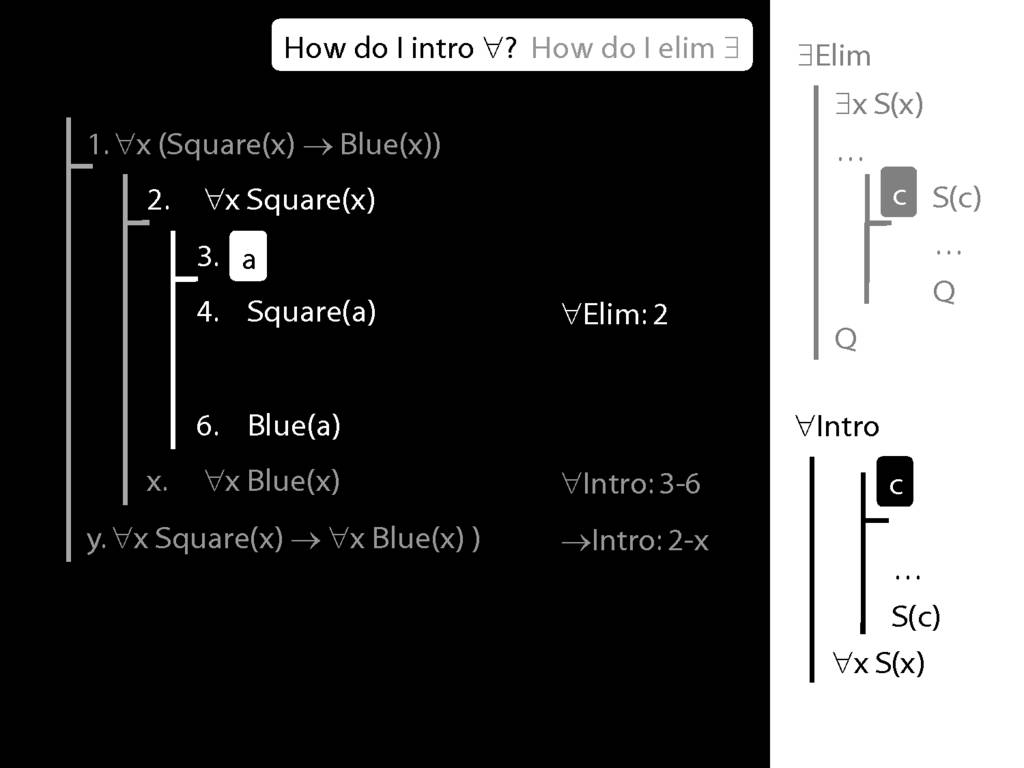

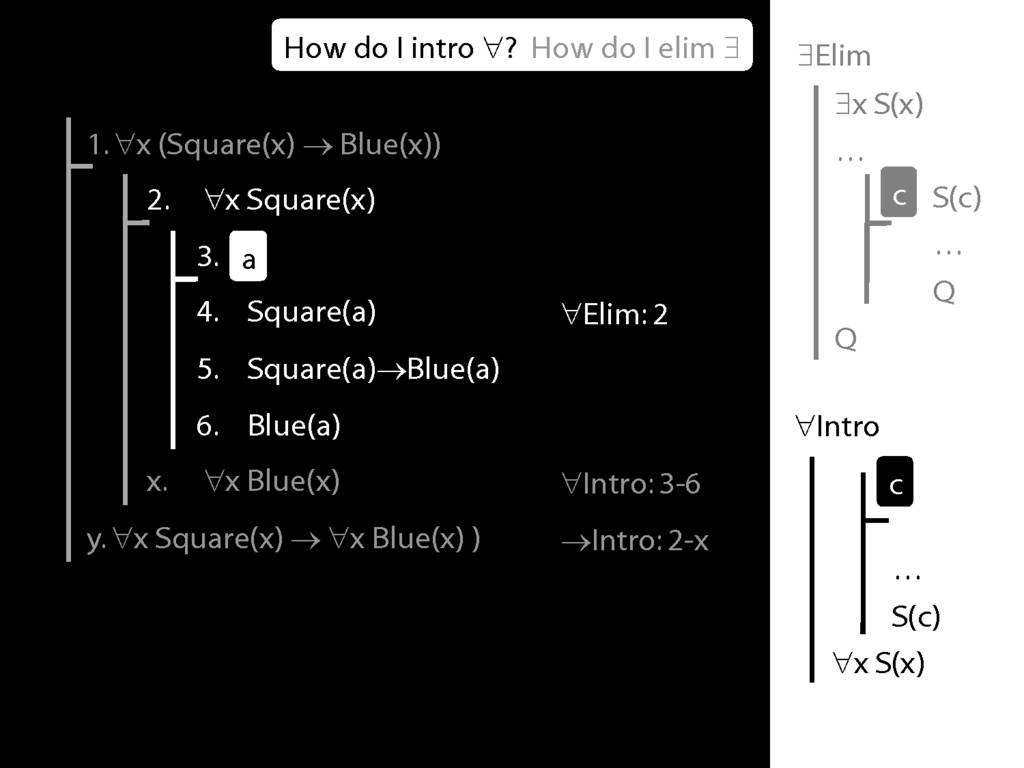

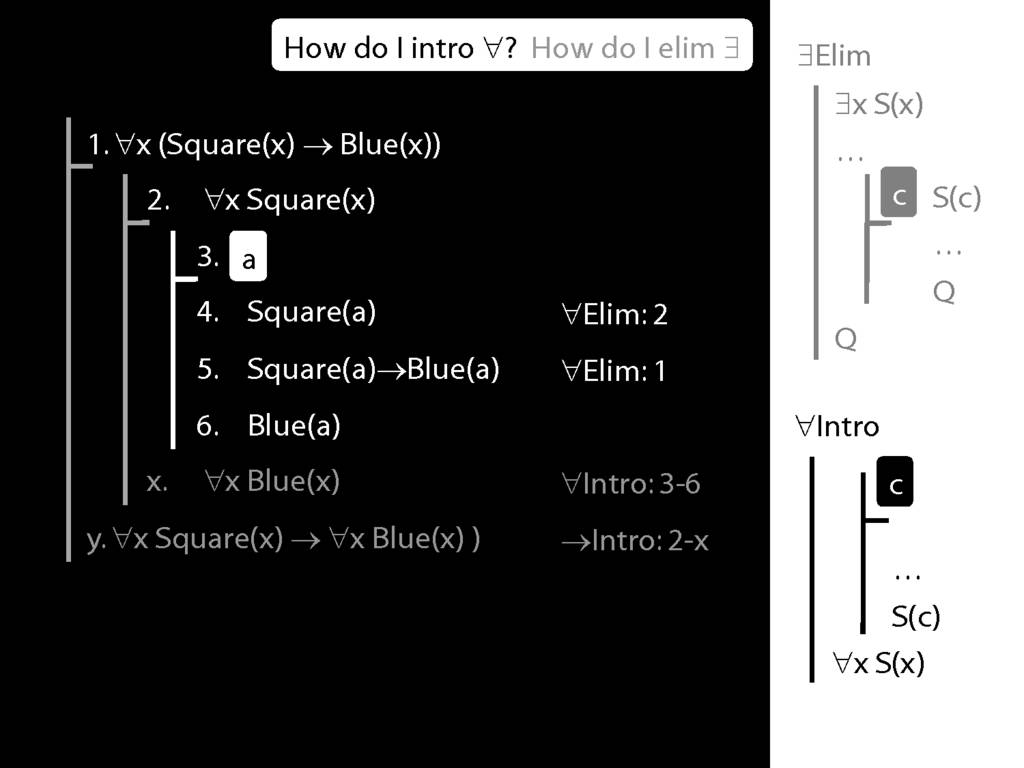

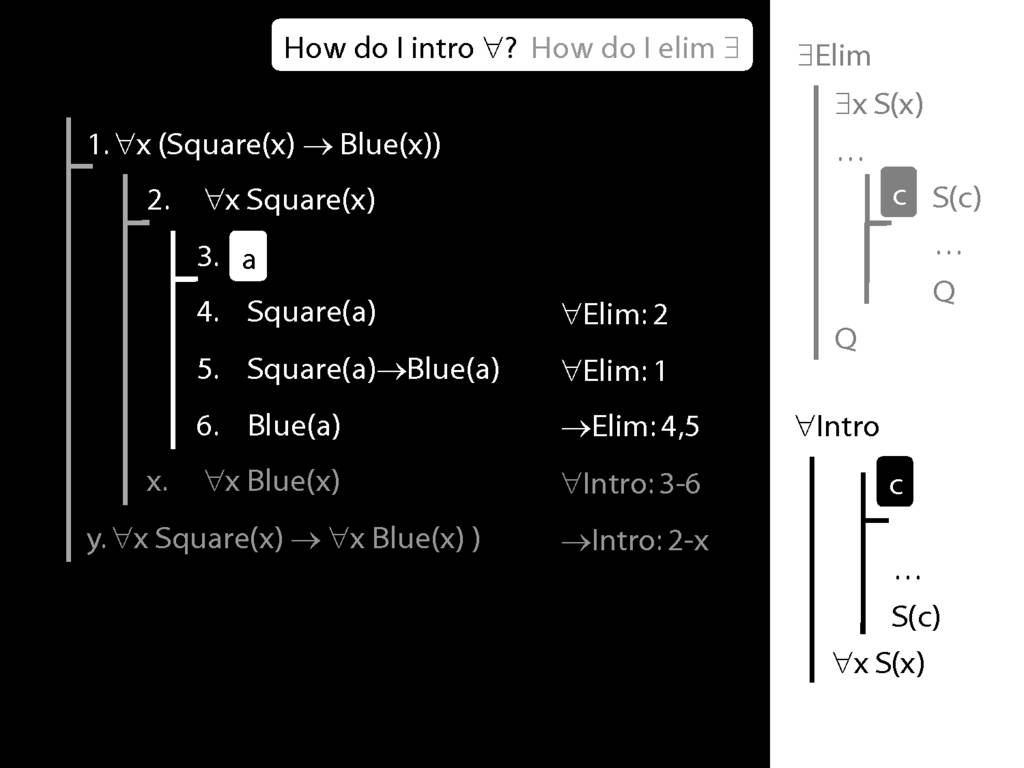

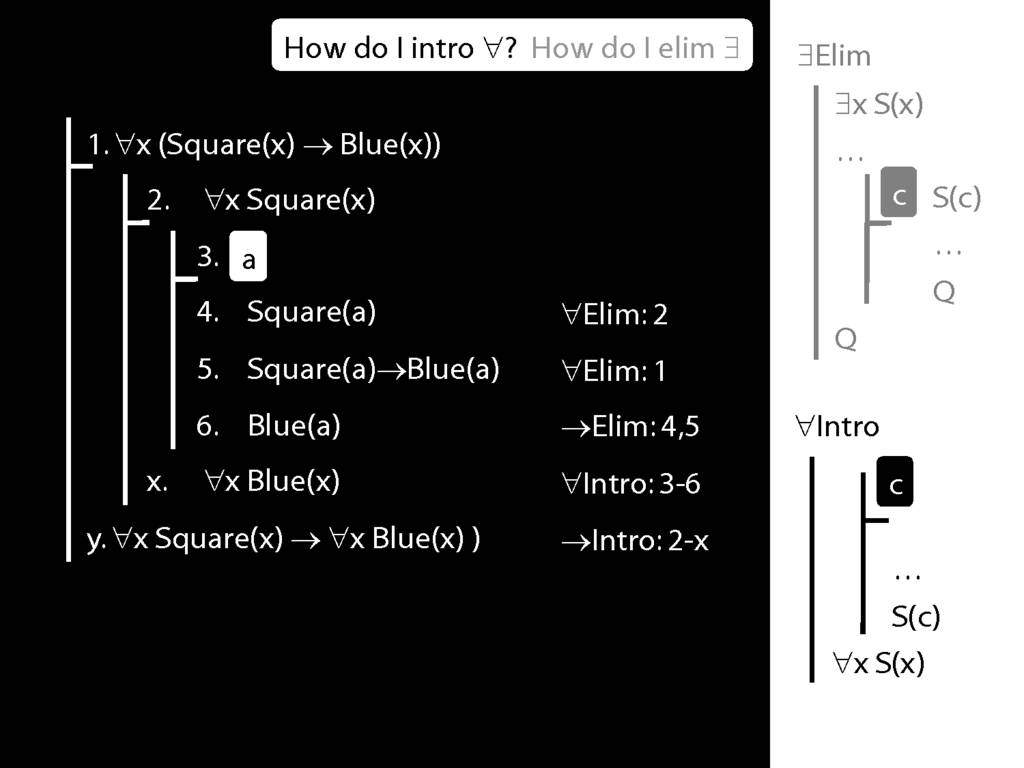

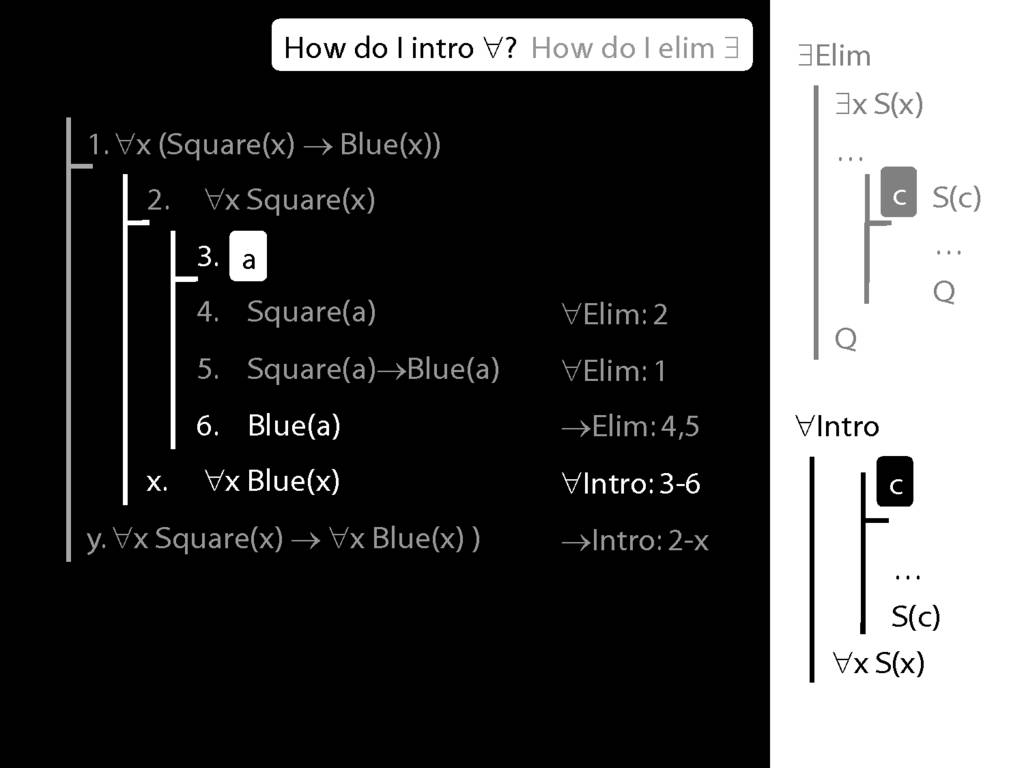

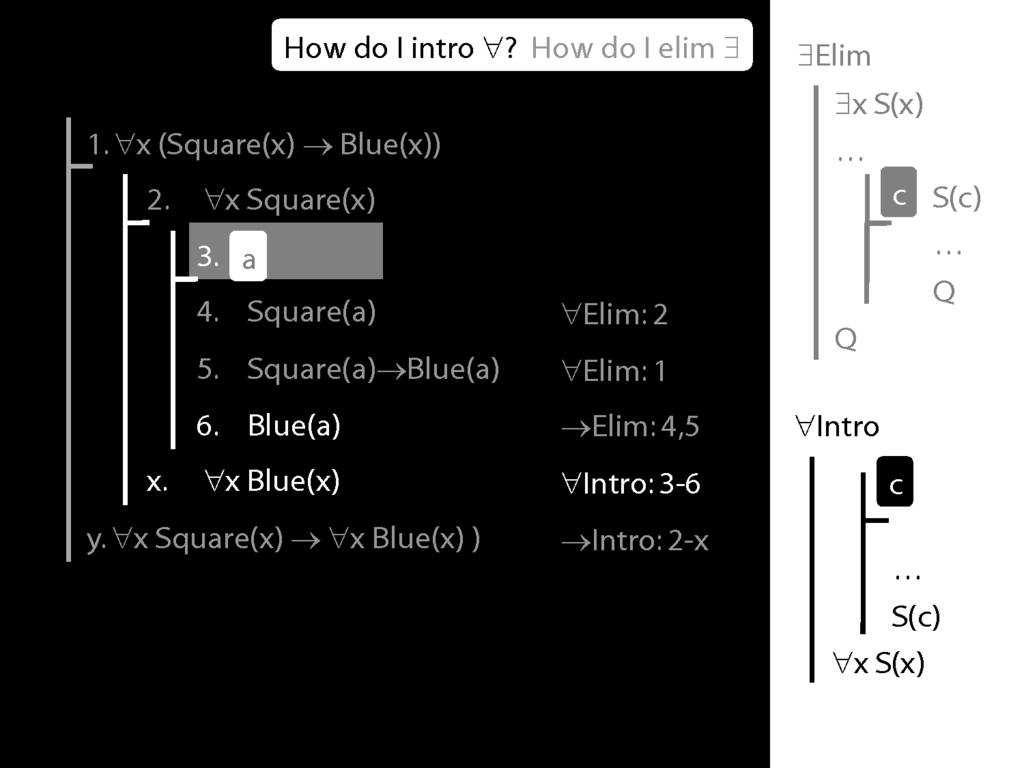

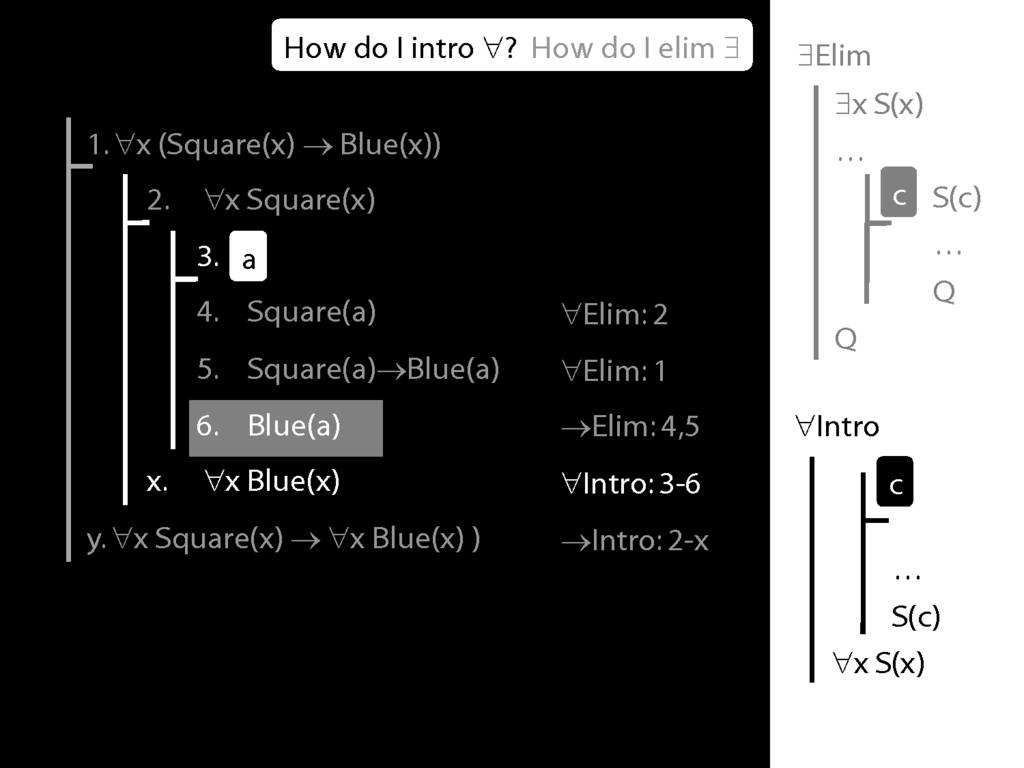

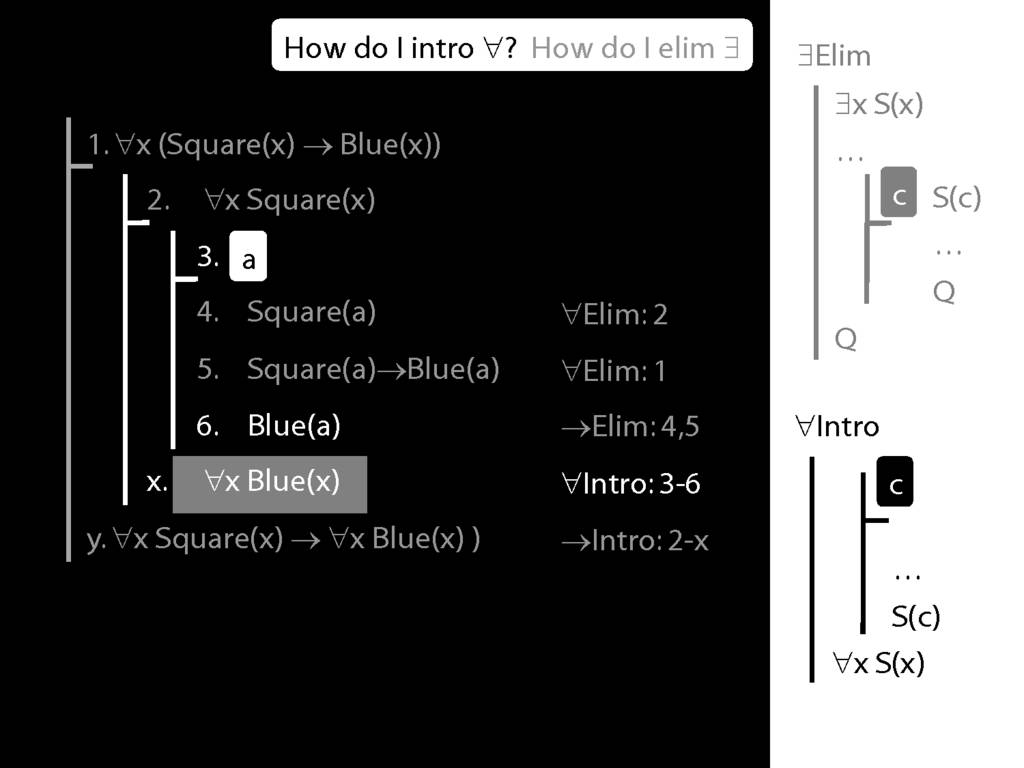

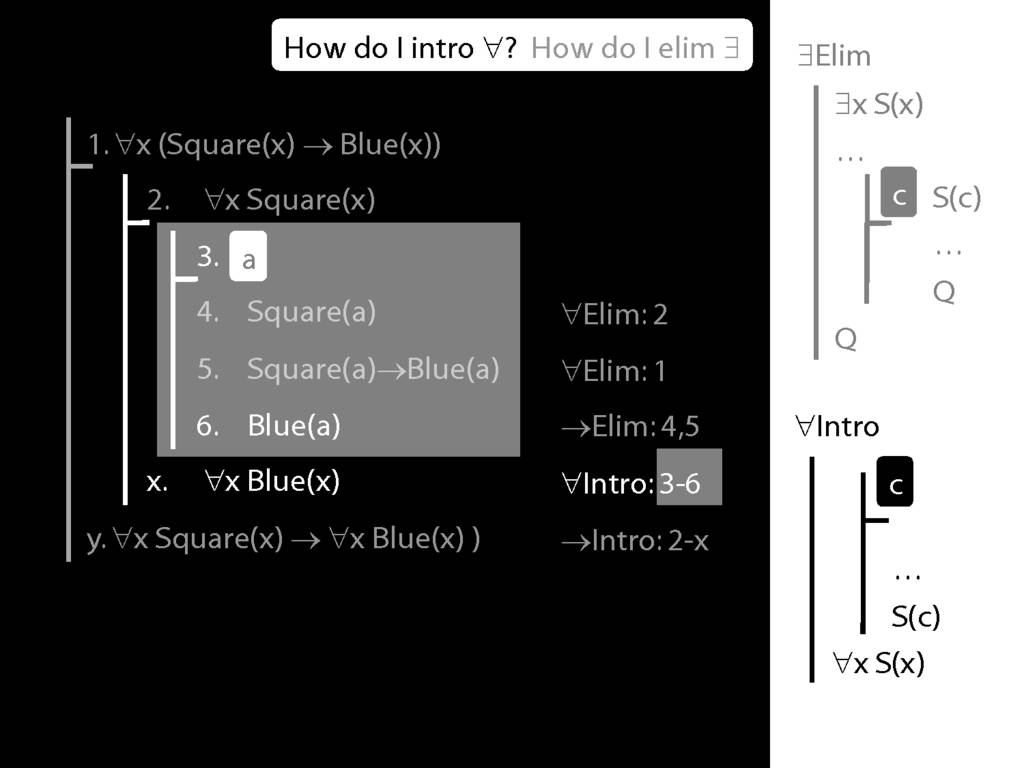

\section{∀Intro}

\emph{Reading:} §12.1, §12.3, §13.1

\begin{minipage}{\columnwidth}

Why is this proof incorrect?

\end{minipage}

12.4--12.5

*12.6--12.7

12.9--12.10

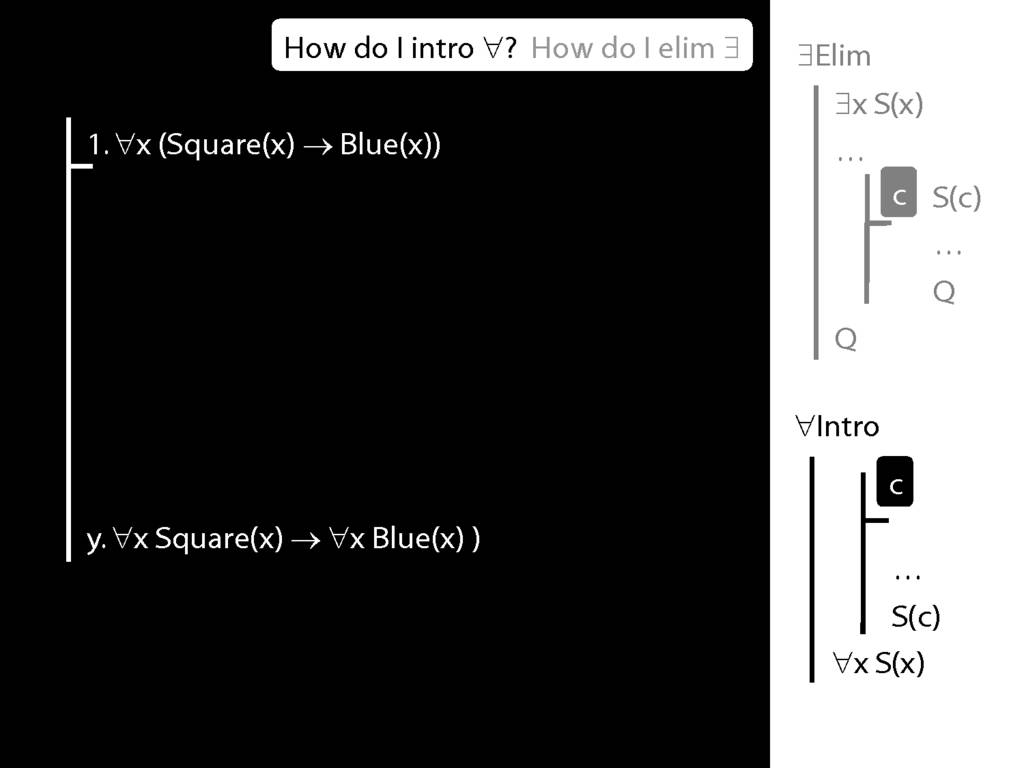

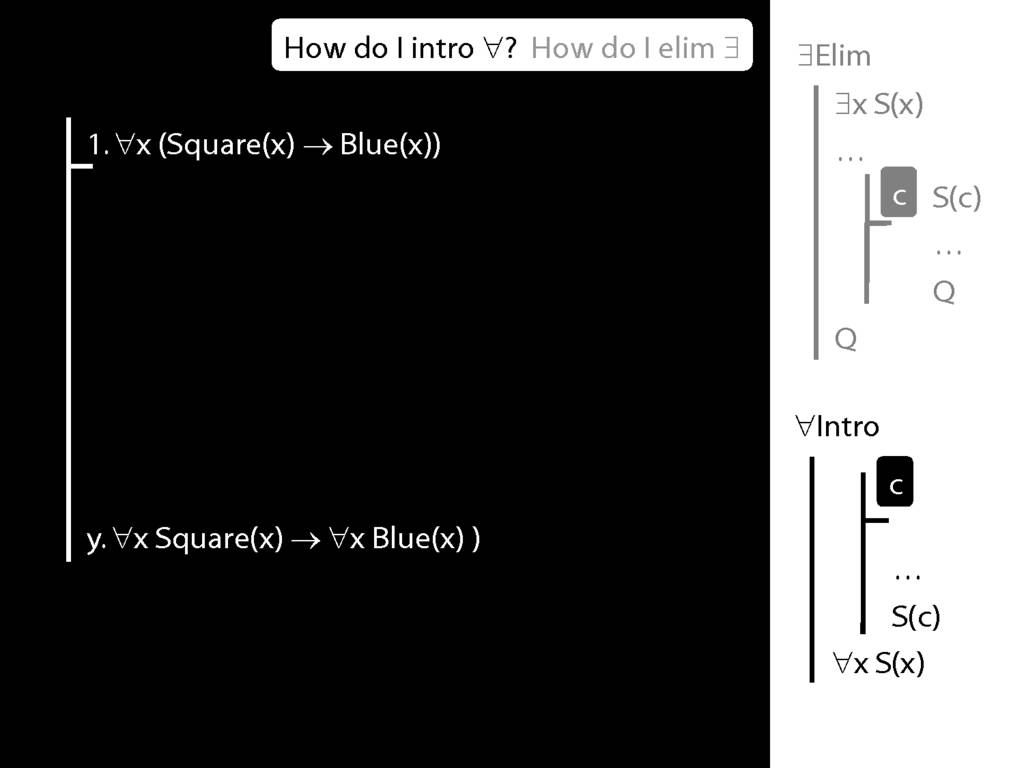

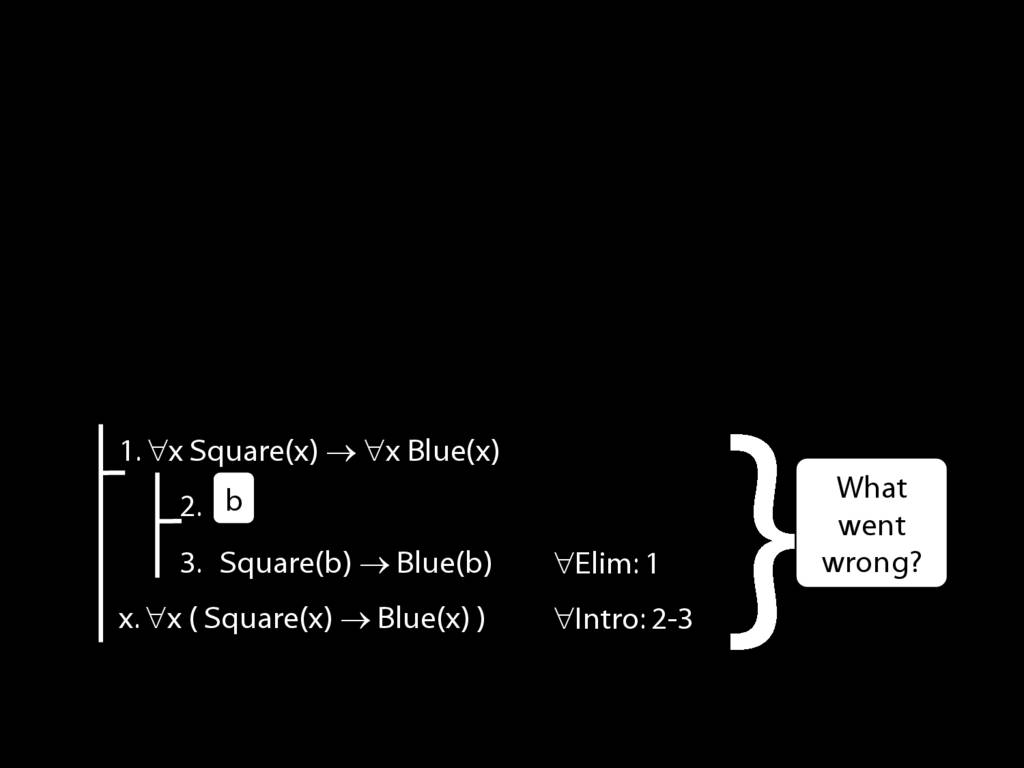

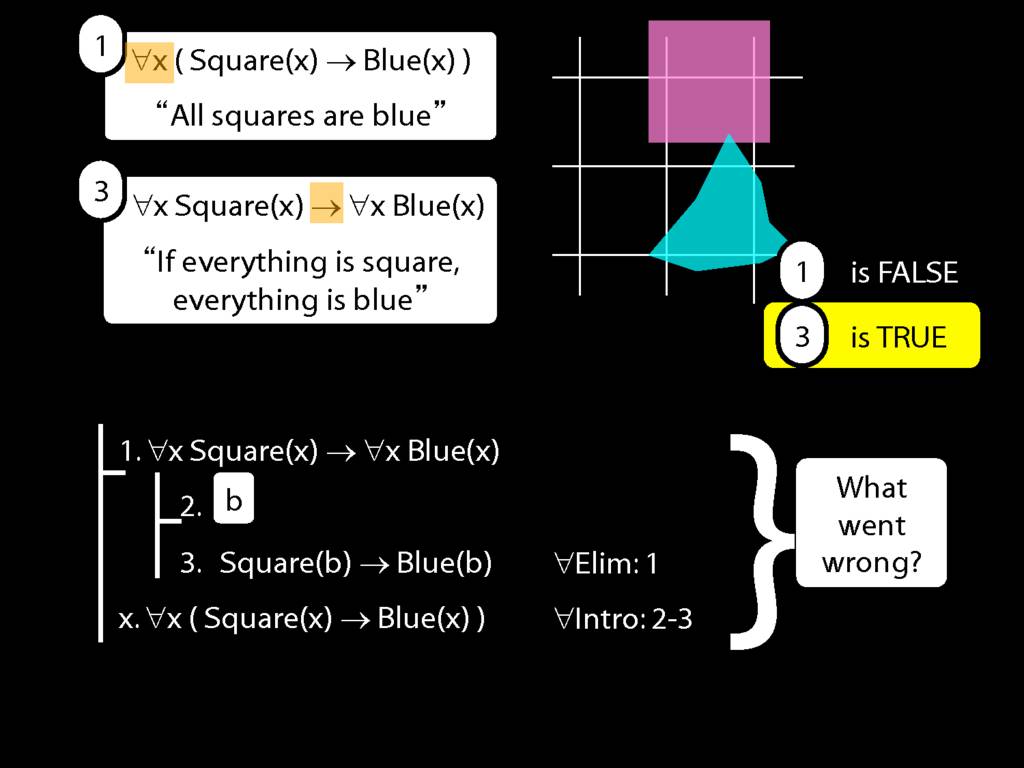

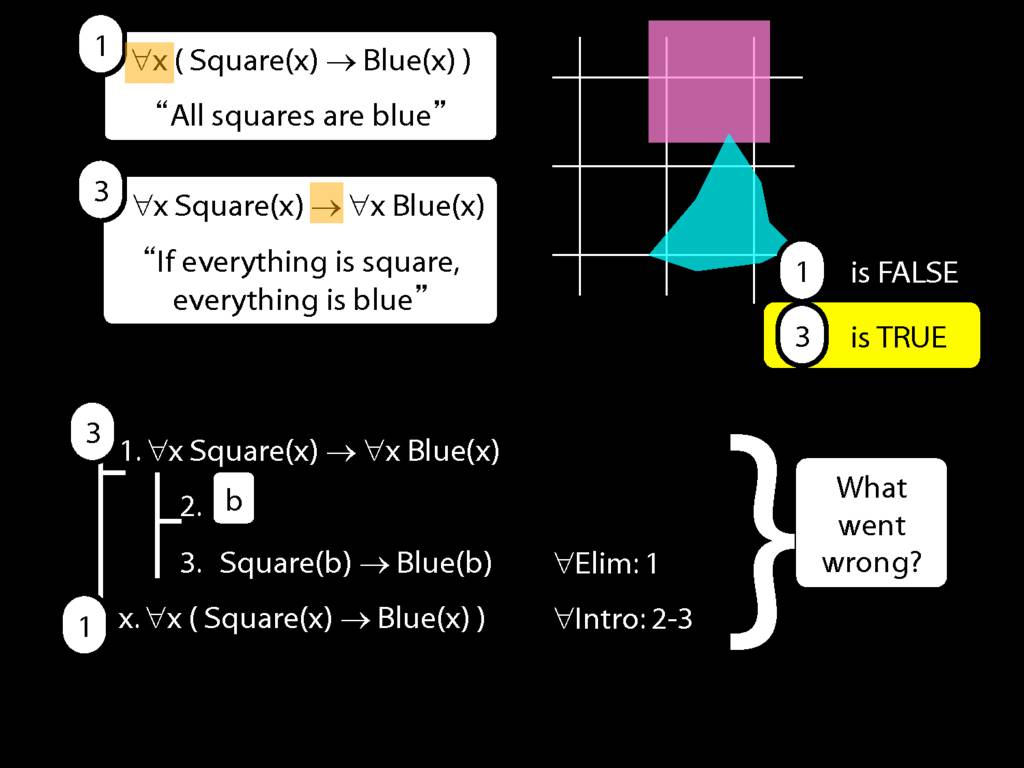

∀Intro: An Incorrect Proof

\section{∀Intro: An Incorrect Proof}

\emph{Reading:} §13.1, §13.2

This proof is wrong, but why?:

There is a counterexample to the argument: