Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Sentence Letters

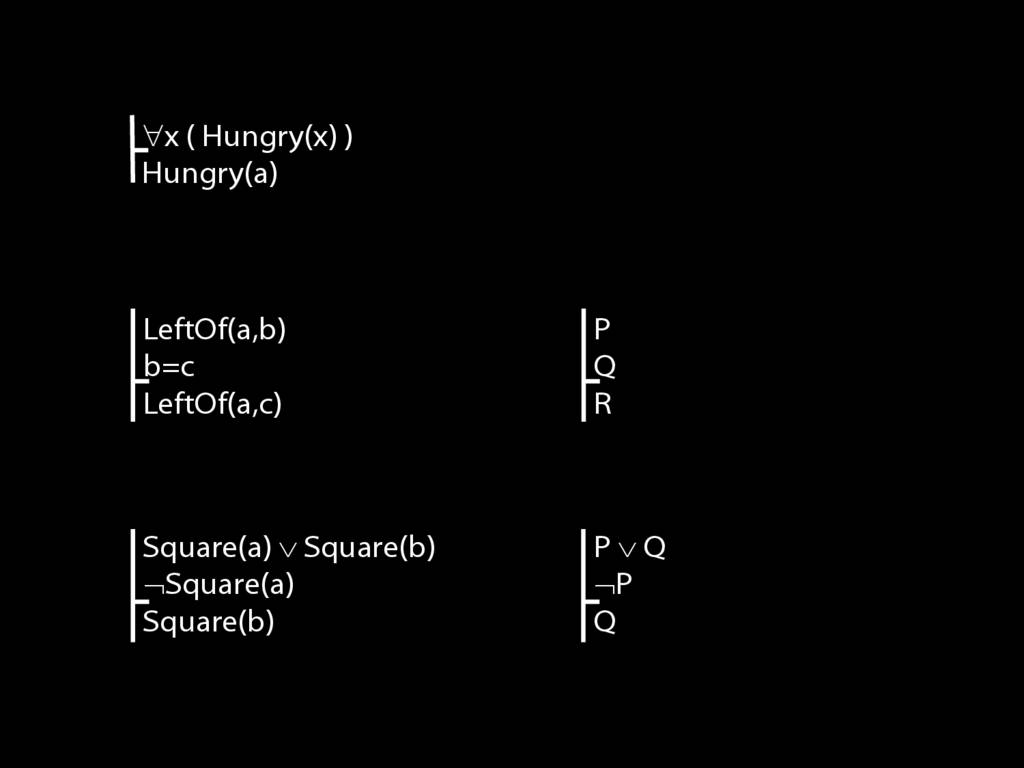

Recall this argument about Ayesha and John.

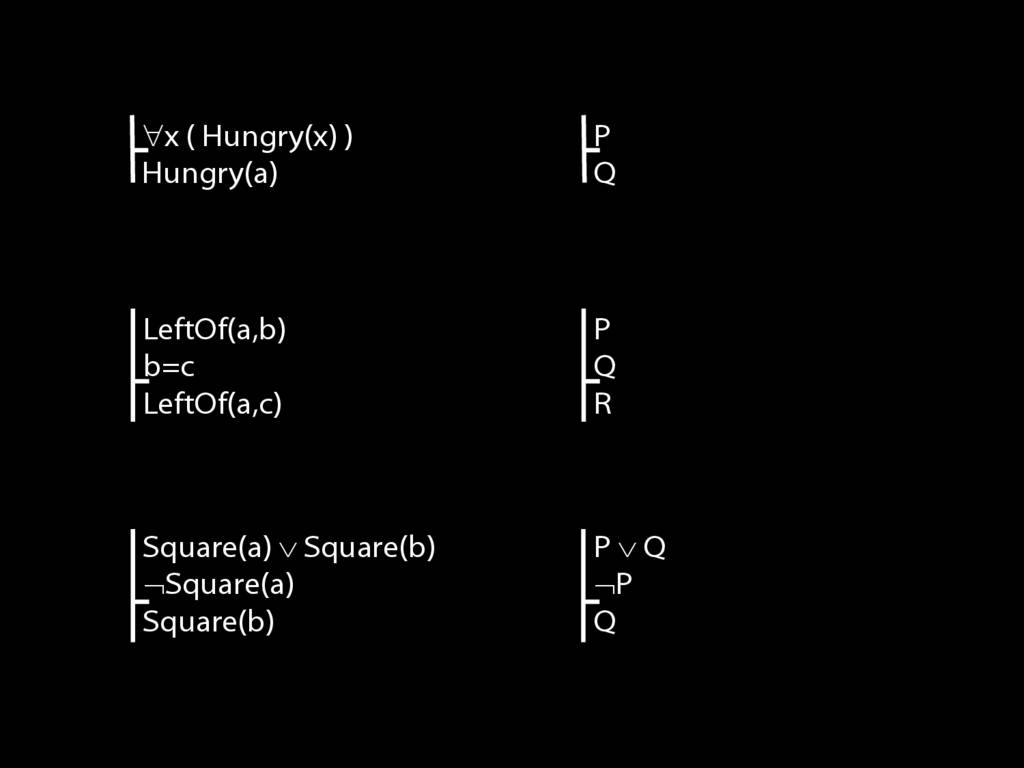

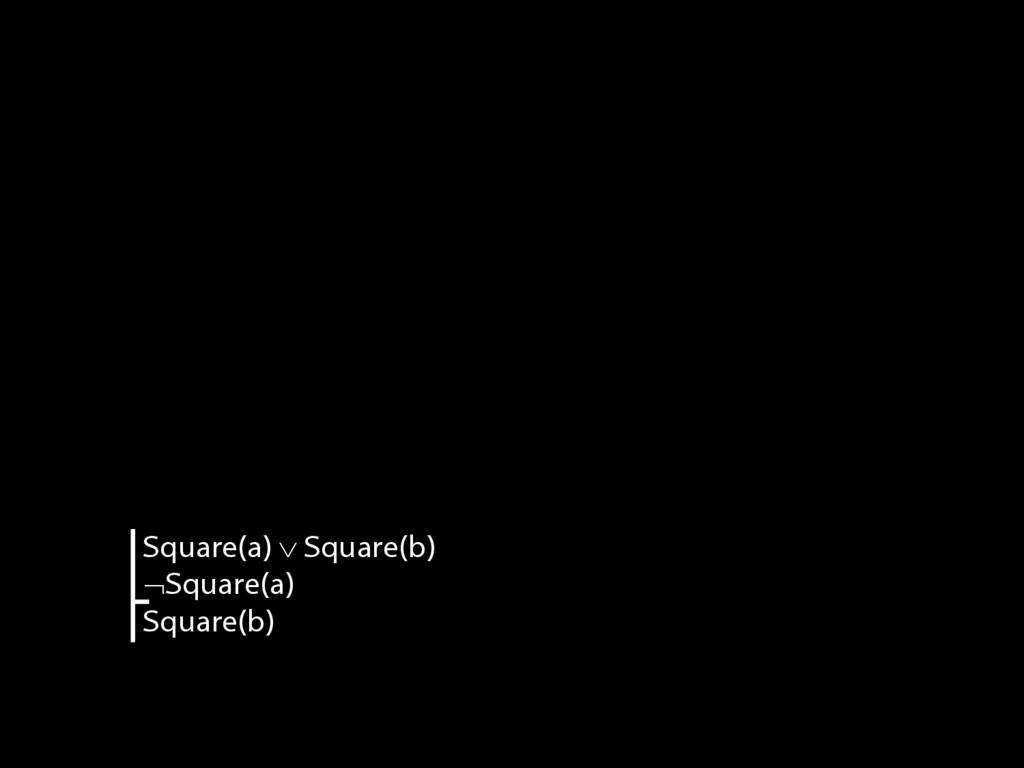

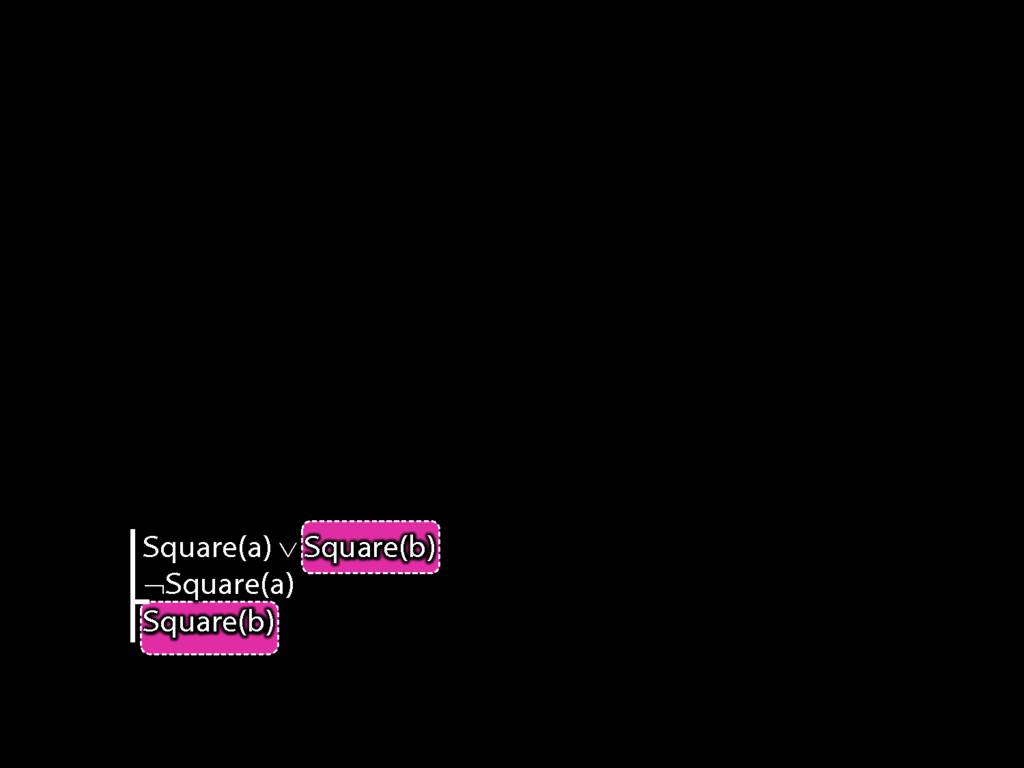

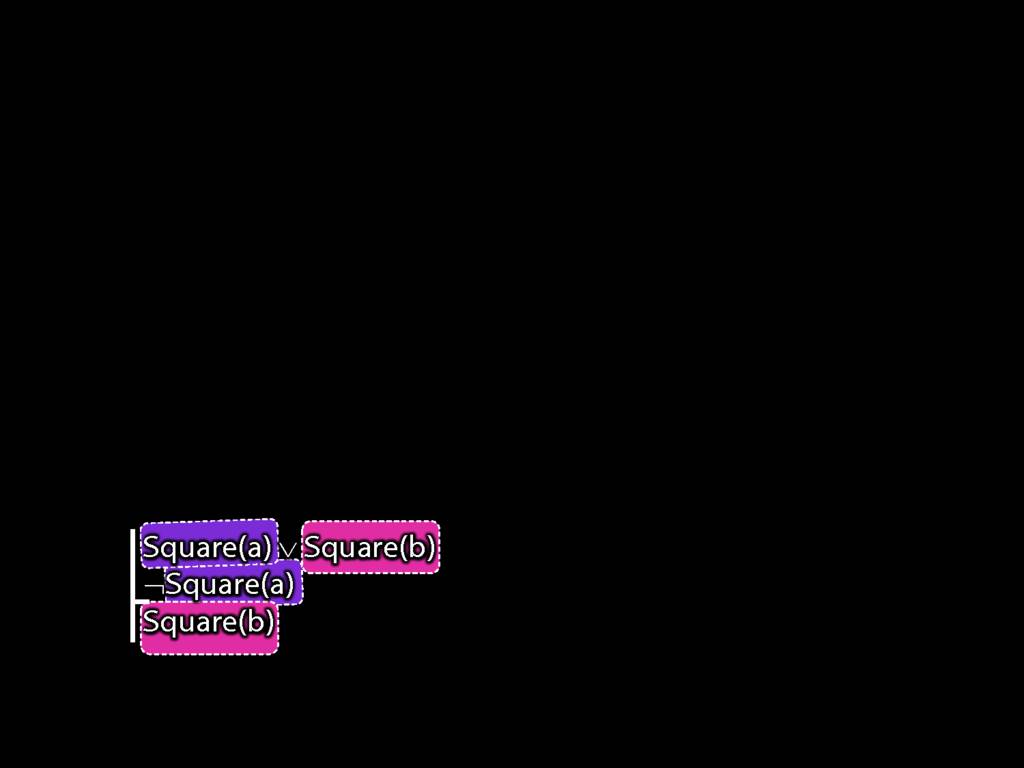

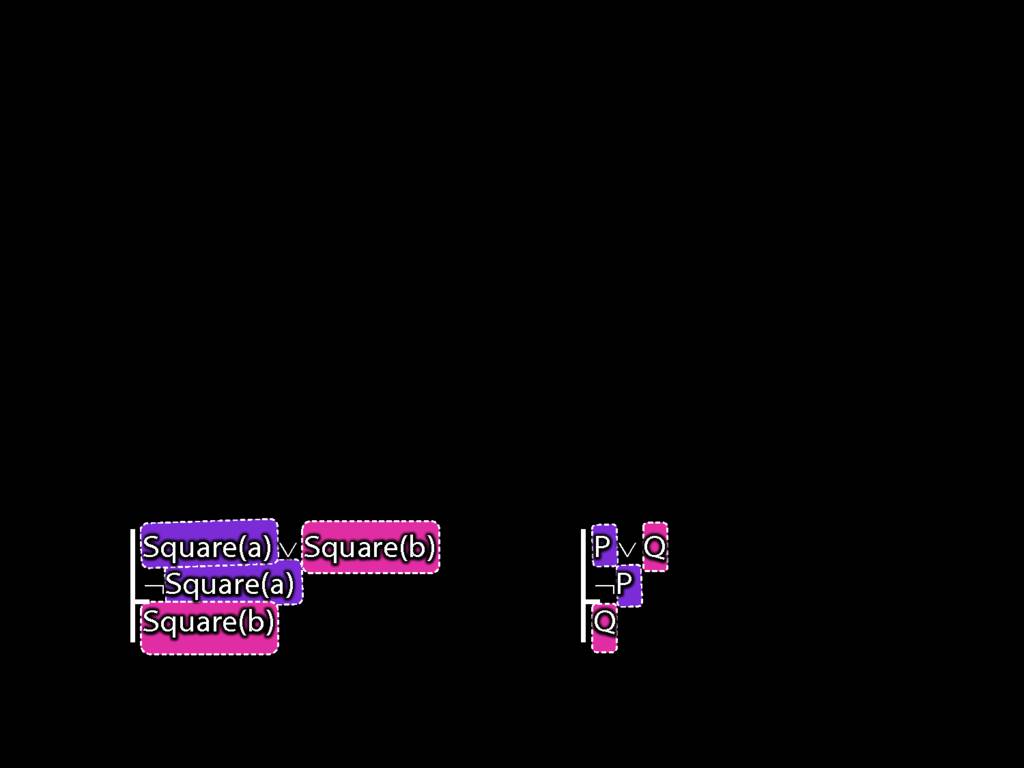

The sentence 'Square(b)' occurs twice, once as part of the first premise, and once as the conclusion.

The sentence 'Square(a)' also occurs twice, once as part of the first premise, and once in the second premise.

And there are no other sentences in this argument.

So we can represent this form of argument in a much more general way ...

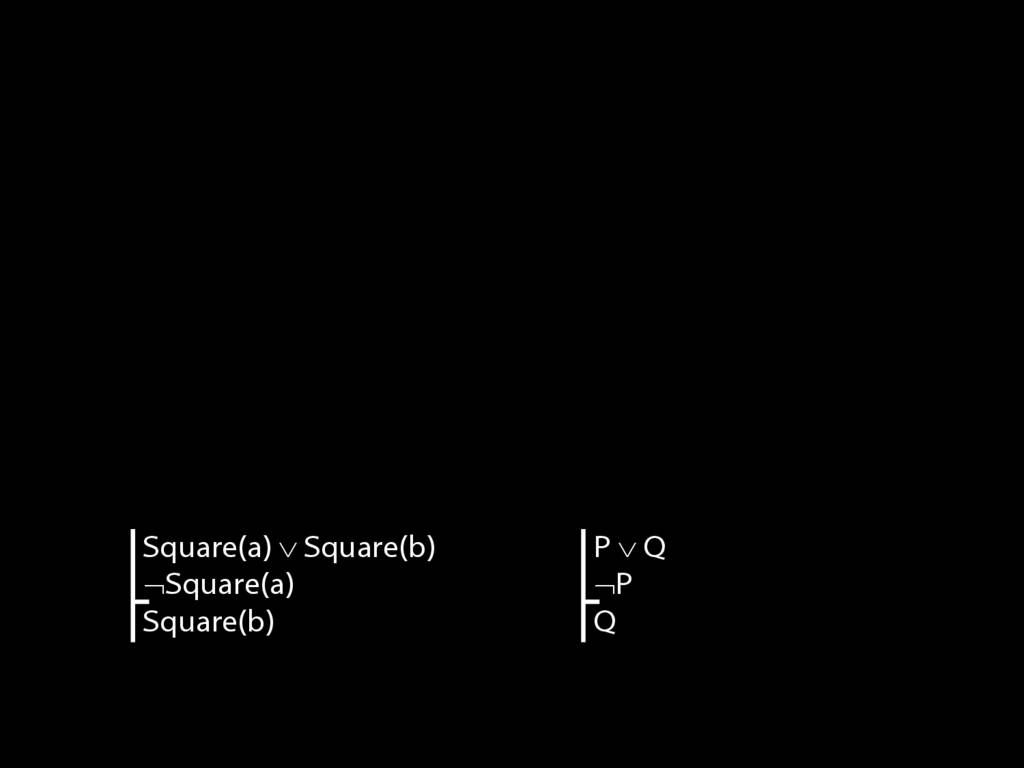

... by using letters to stand for sentences instead of names and predicates.

Why is this more abstract representation useful?

We don't want to consider arguments one-by-one. We want to be able to

say things about a large number of arguments. The use of sentence letters lets us talk abou a much larger class

of arguments, all of which are valid in virtue of having this form.

But how far can we go with sentence letters?

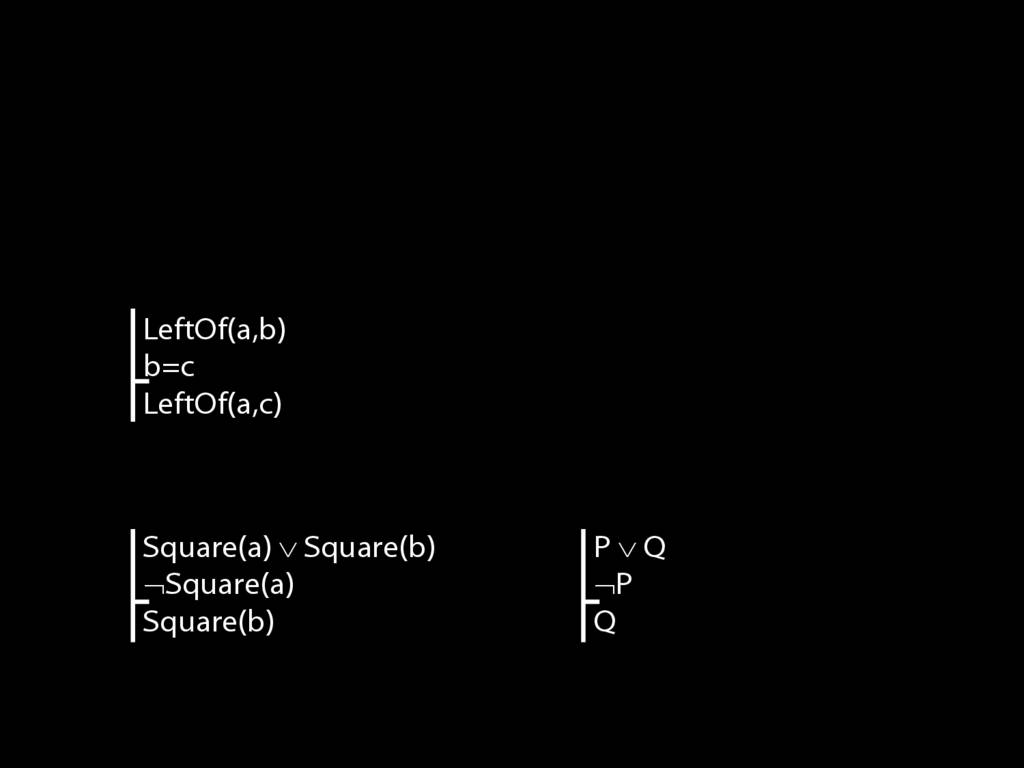

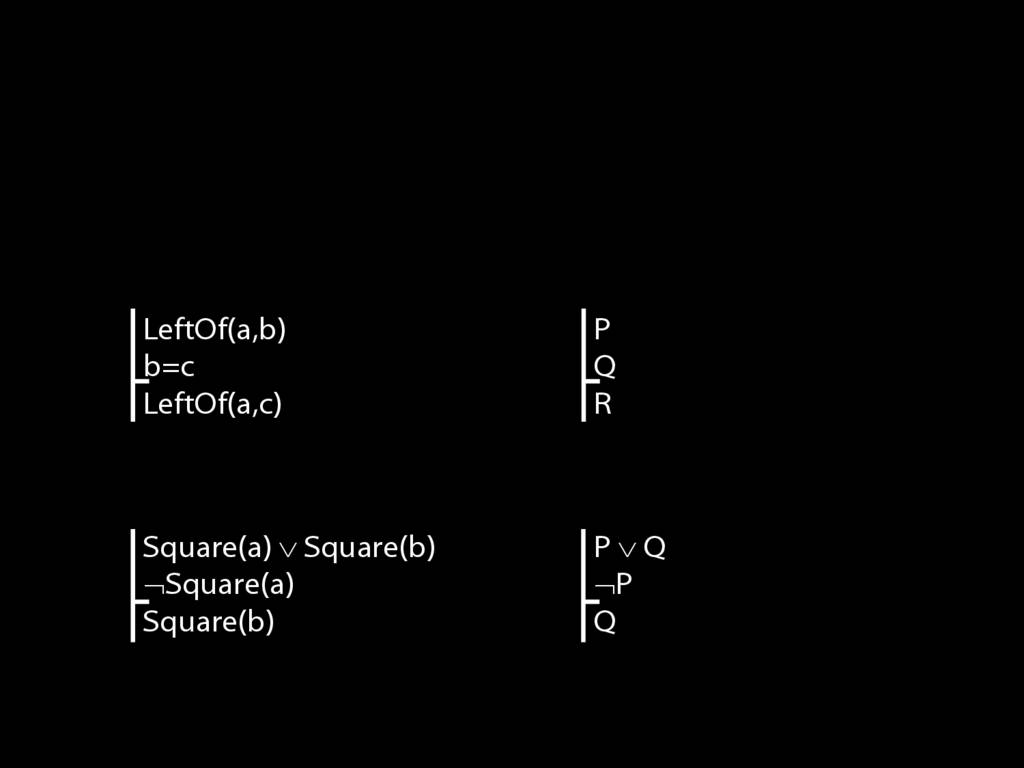

Consider this argument. There are three atomic sentences.

So if we wanted to represent it using sentence letters only, we'd have to have three different sentence letters.

But now we have lost what is interesting about this form of argument.

After all, any argument with two premises and a conclusion has the form P, Q therefore R.

There's nothing interesting we can say about all arguments with *this* form.

So where an argument exploits identity, we can't capture what's logically interesting about its form using sentence letters.

The same is true where an argument exploits quantifiers ... this is something we'll get to later in the course.