Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Identity

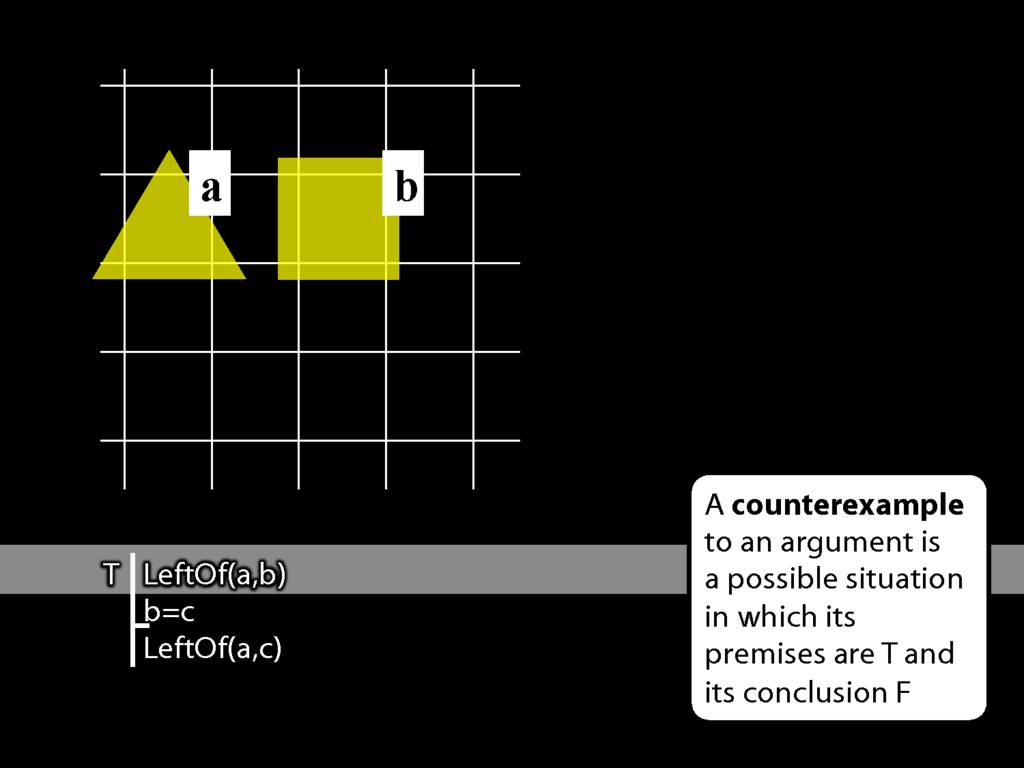

Here’s an argument involving identity. Let’s see if it’s valid.

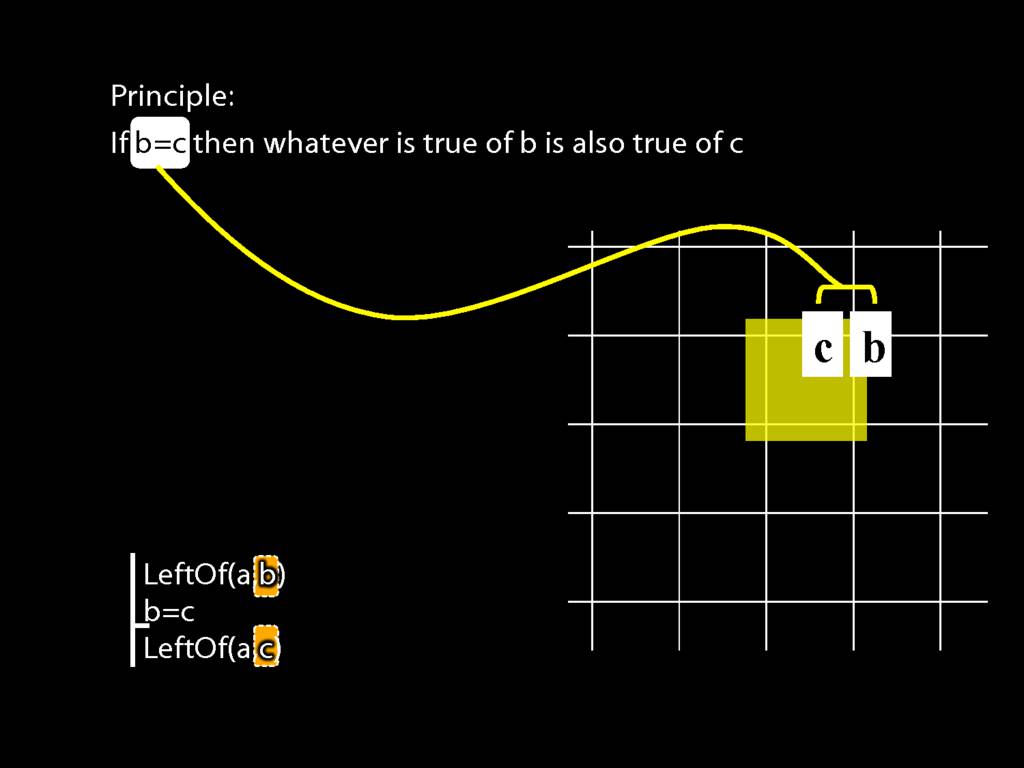

Principle: If b=c then whatever is true of b is also true of c.

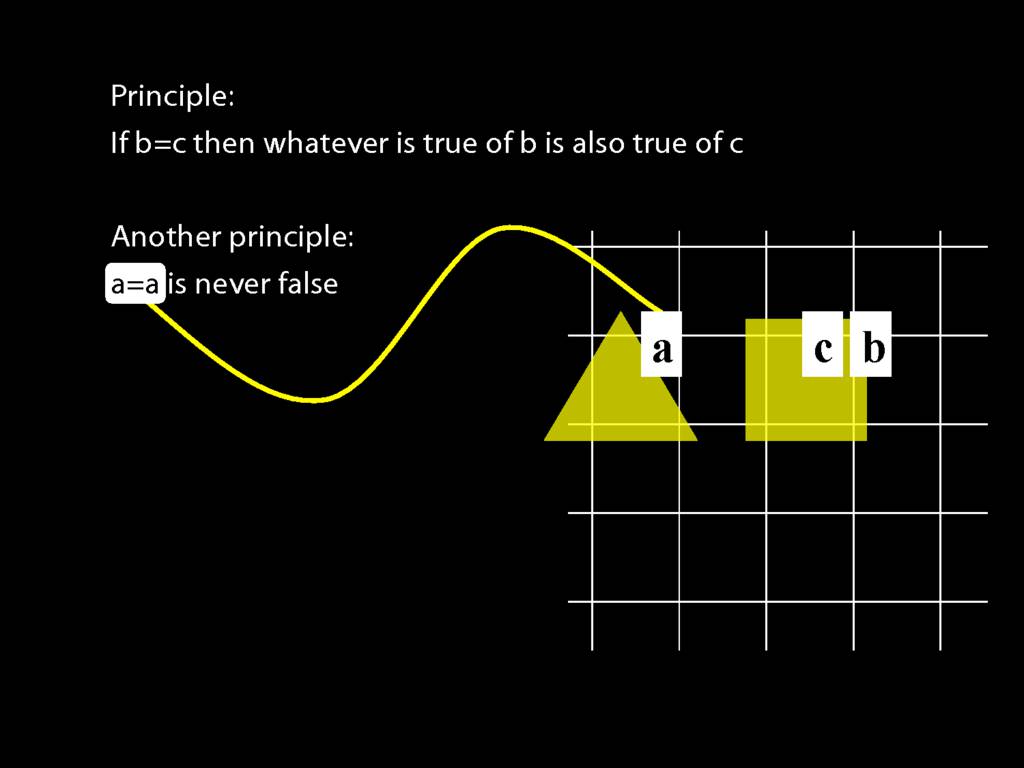

Principle: a=a is never false

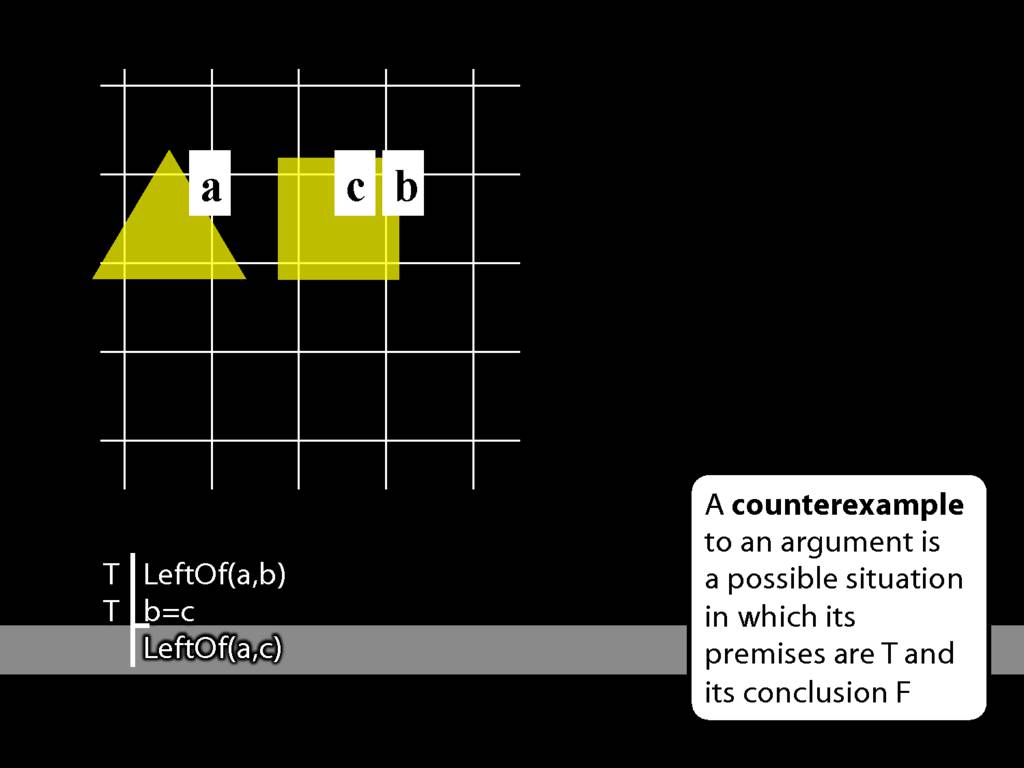

Suppose we want to find a counterexample. So we need to make make the premises true. Let’s see if we can make them true without making the conclusion true.

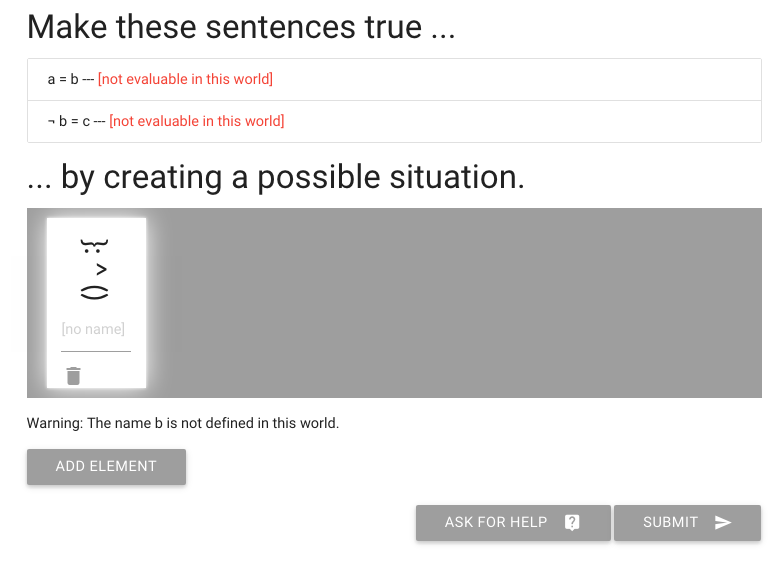

Start with an empty world.

Consider the first premise

We want the first premise to be true so we have to put a to the left of b.

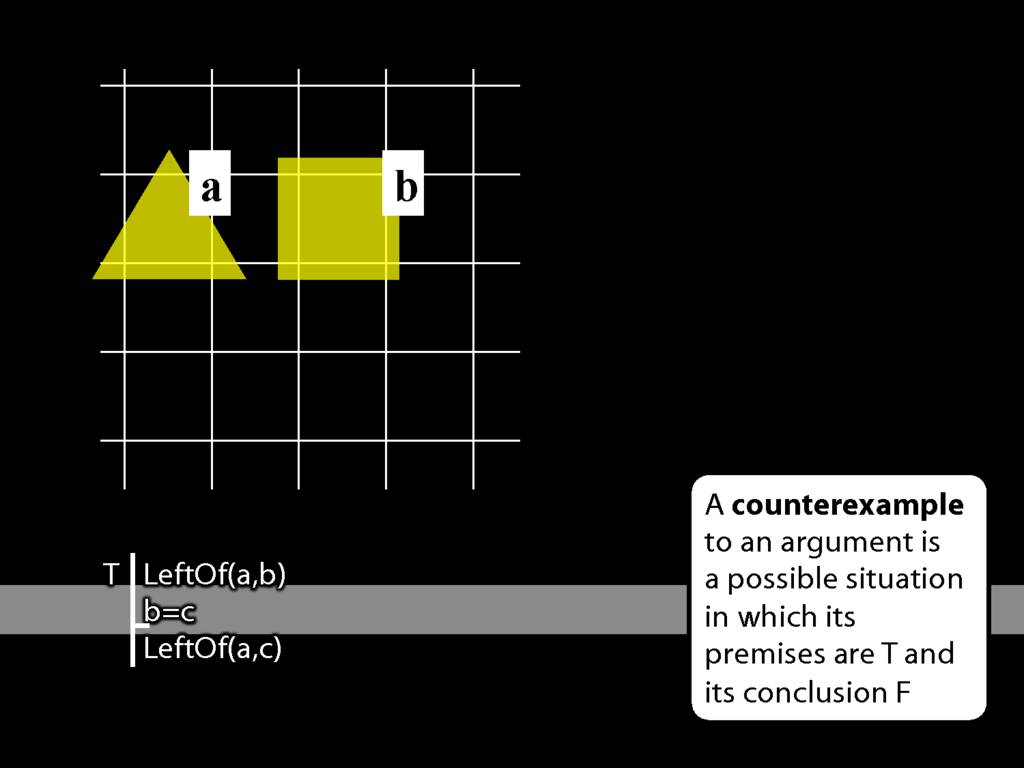

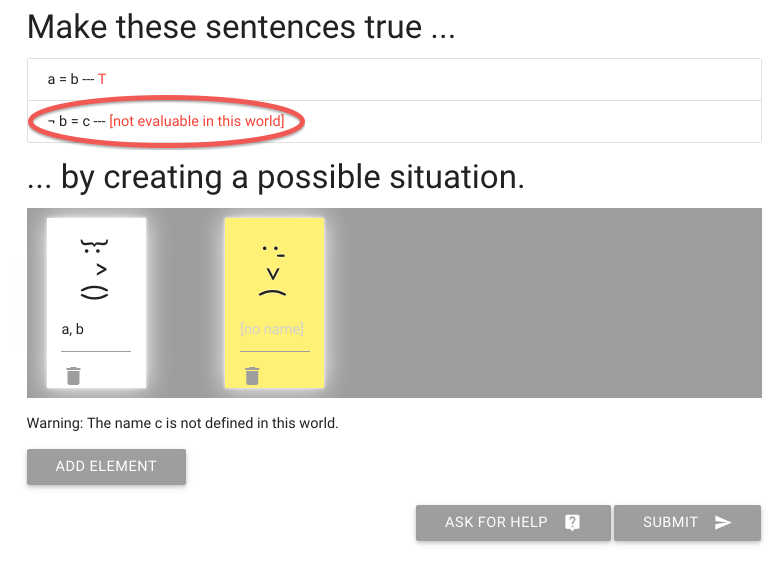

What about the second premise? So far the truth-value of the second and third premises are undefined because the name ‘c’ does not yet designate any object in this situation.

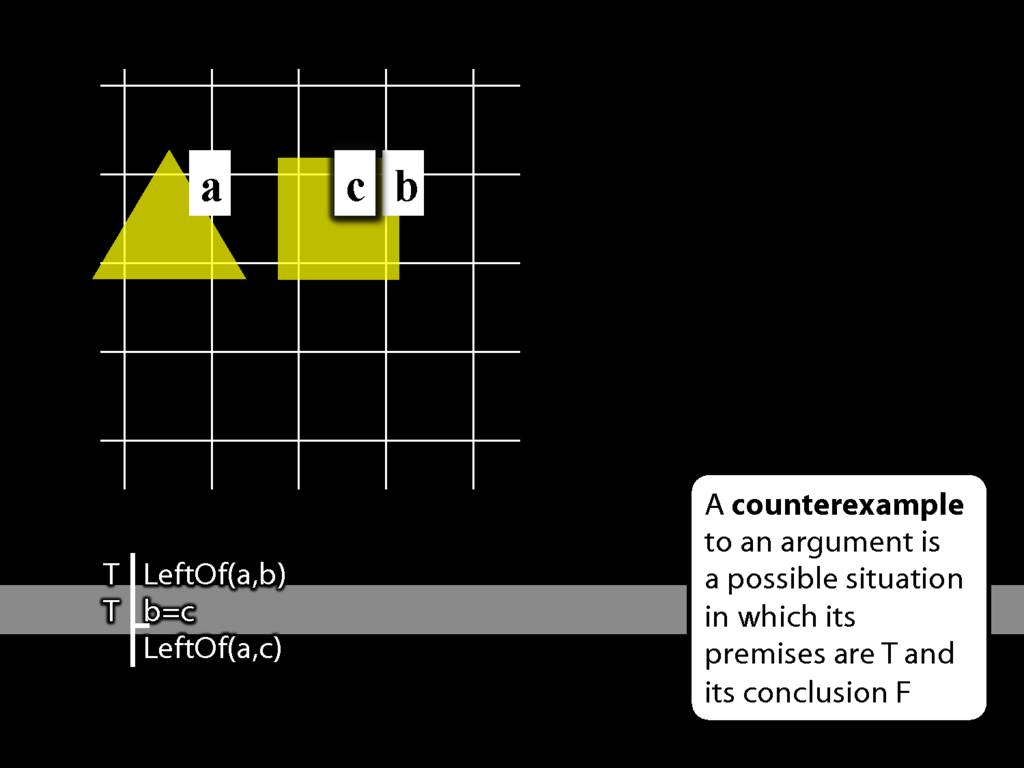

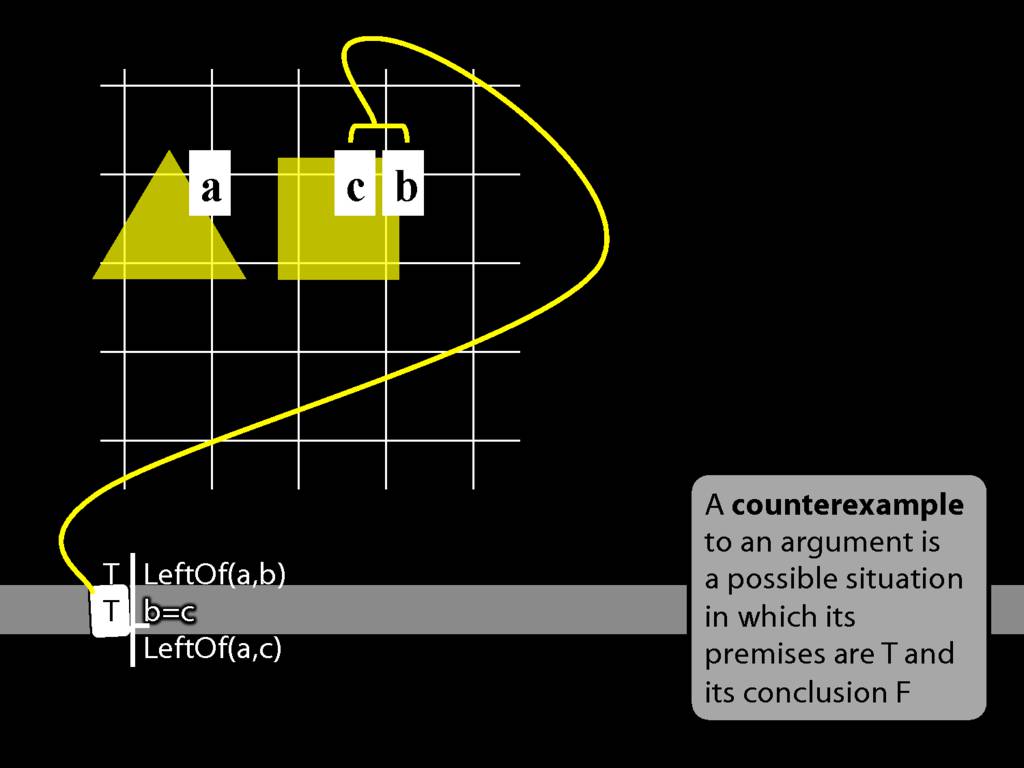

Want the second premise to be true so we have to label the b object c as well.

This is what b=c requires--that one and the same object have both labels.

Now, what about the conclusion?

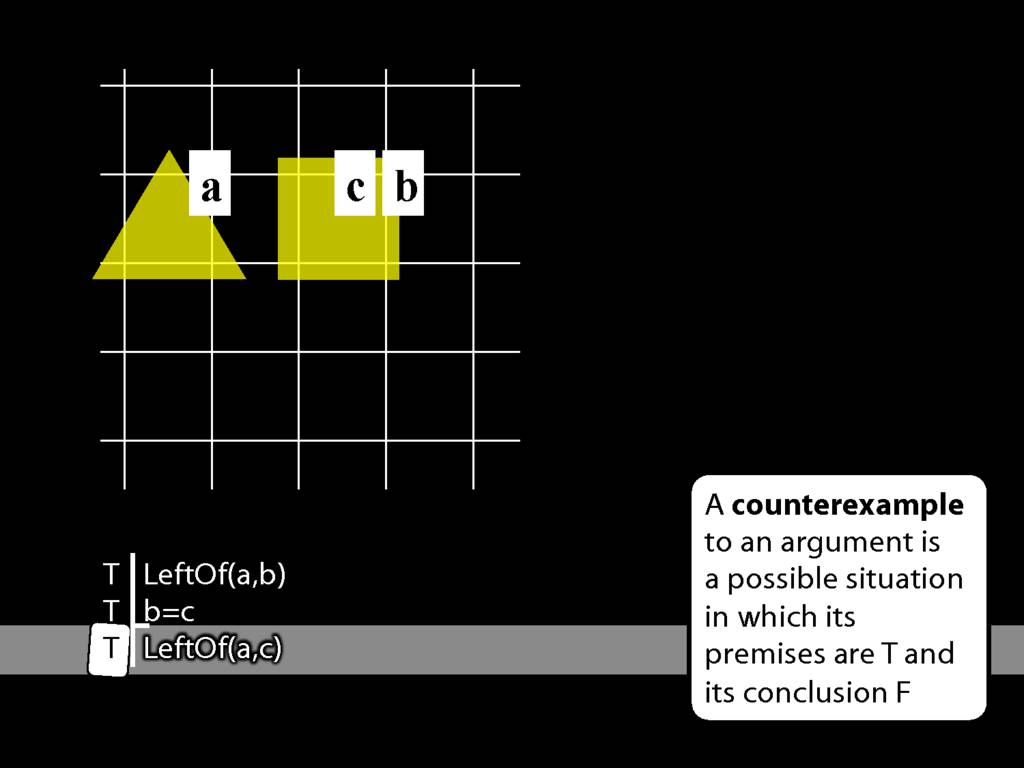

Having made the premises true, the conclusion turns out to be true as well.

This is sort of an informal proof that the argument is valid. If you think about what is involved in making the premises true, you can see that it guarantees the truth of the conclusion as well.

As far as the logic of identity goes, all you need to know are two principles.

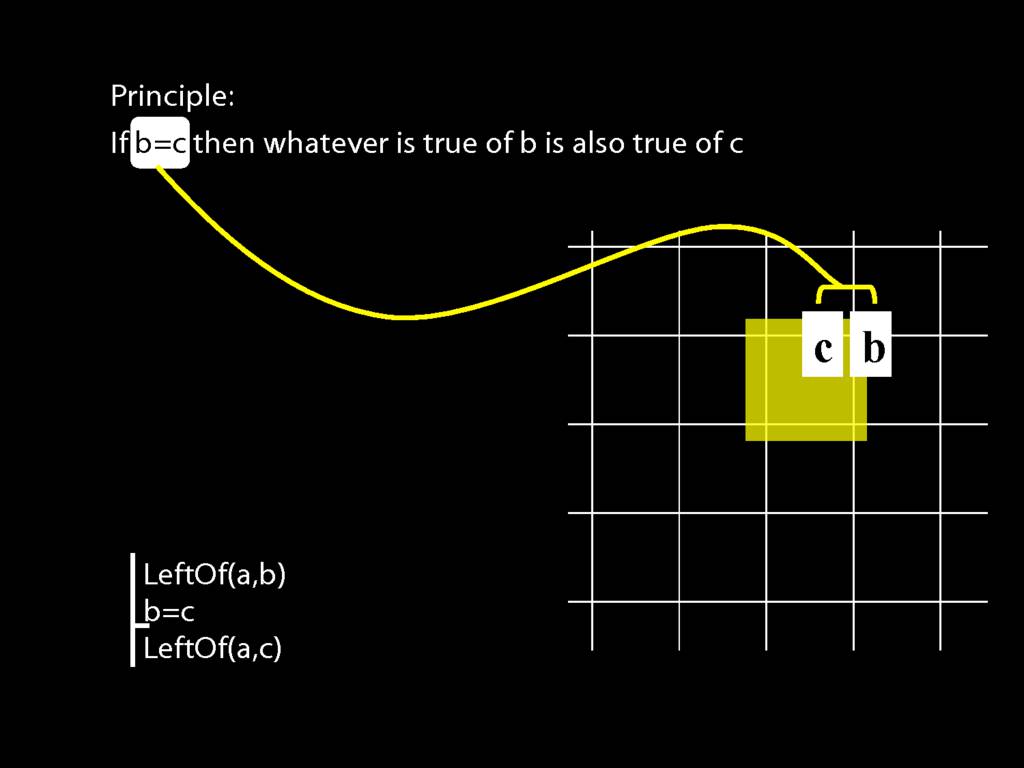

This first principle.

You can see that this principle must be true from the meaning of identity: b=c requires that one and the same object have both labels.

And this first principle is exactly what you need to prove the argument we were just looking at.

The second principle says, roughly, that everything is identical to itself.

You can see that this principle must be true from the meaning of identity: a=a requires only that one and the object named 'a' be named 'a', which you can't really avoid. (In case you're thinking there's a tricky issue about what happens if nothing is named 'a', well done. In our system of logic, we rule that possibility out by stipulation to keep things simple.)

These principles are all you need to understand the logical notion of identity. They allow you to do things like prove that identity is a symmetric and transitive relation.

I want to show you quickly how to work with identity in logic-ex.

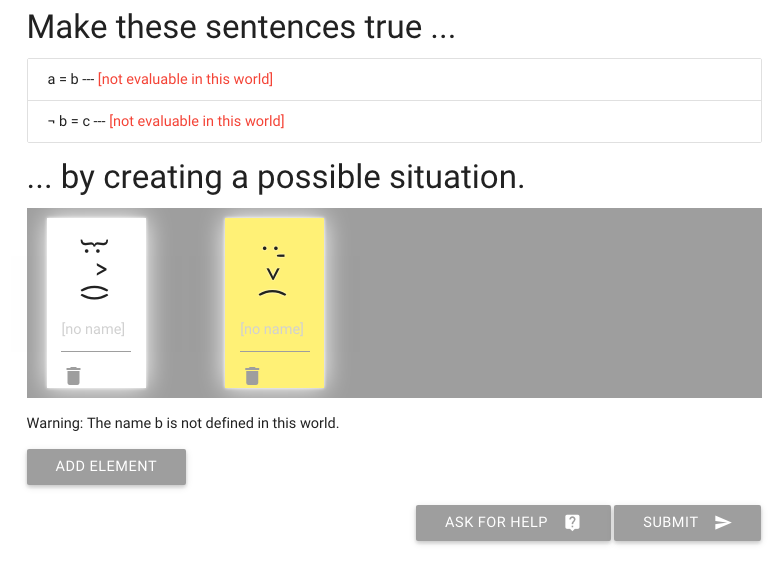

Let’s add a person to the possible situation

Here I’ve added some names

I’ve called one person ‘a’ and the other ‘b’.

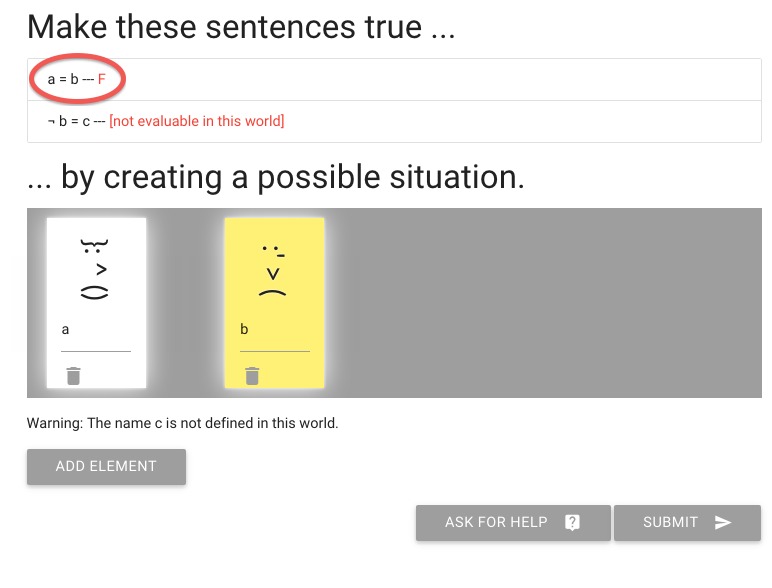

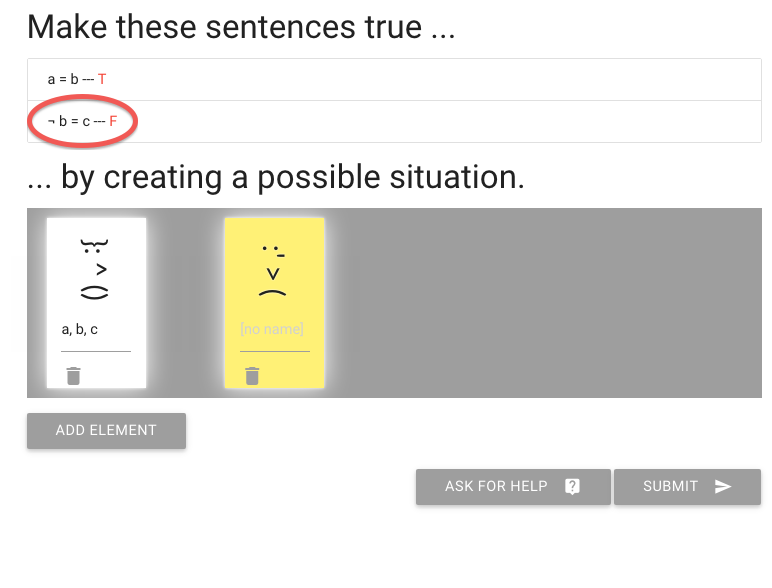

Of course this makes the first sentence false, not true.

How do I make it true?

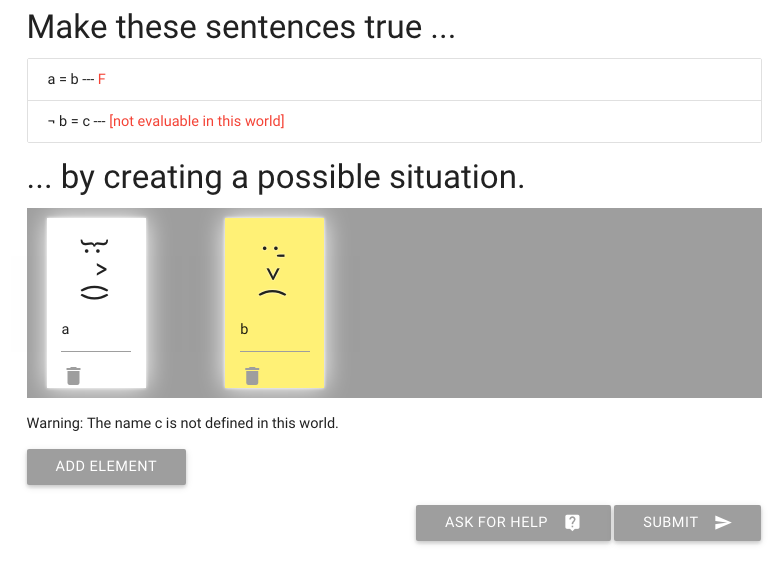

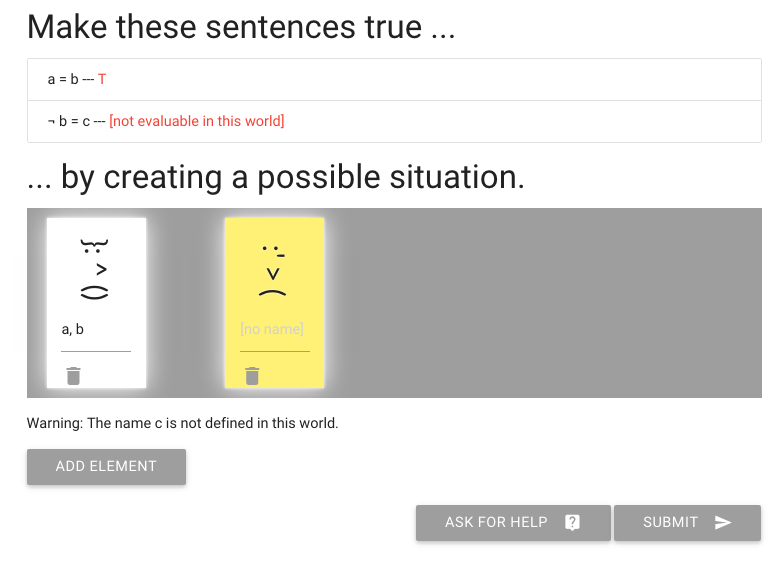

Like this ...

I’ve given one person both names.

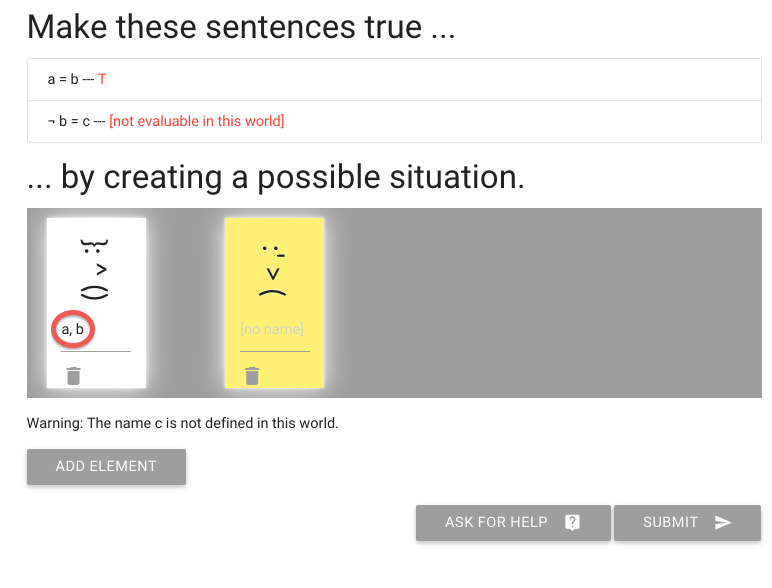

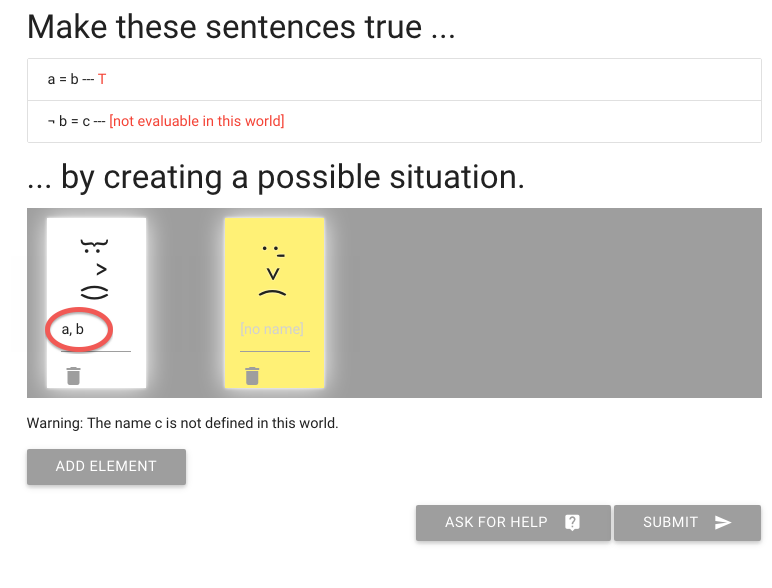

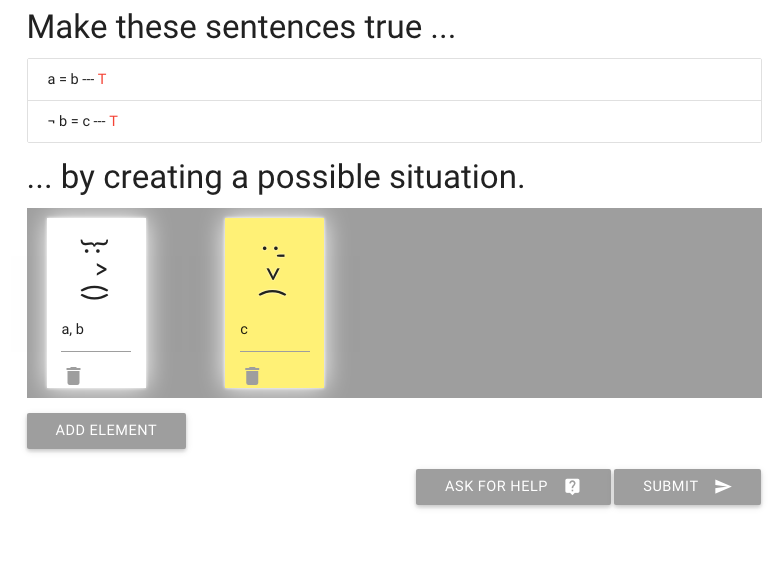

To give more than one name to a person, simply type multiple names

separated by commas or spaces (or both), just as I’ve done here.

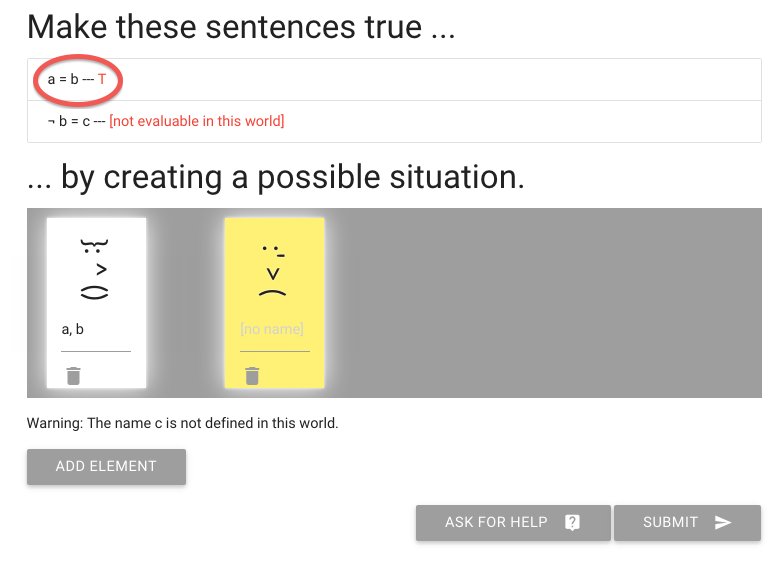

And this makes the sentence ‘a=b’ true, of course.

But what about the next sentence, ‘not b=c’?

To make this true or false, I need to give someone the name c.

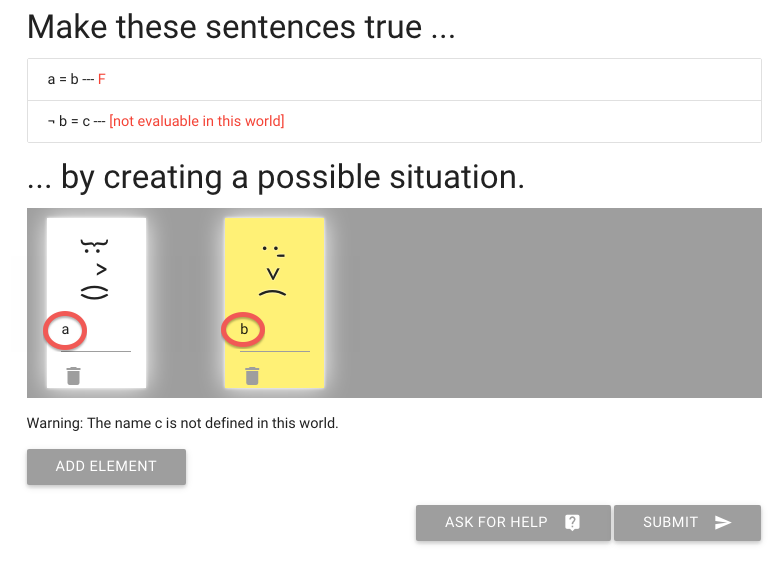

I’m going to add that to the person already known as ‘a’ and ‘b’.

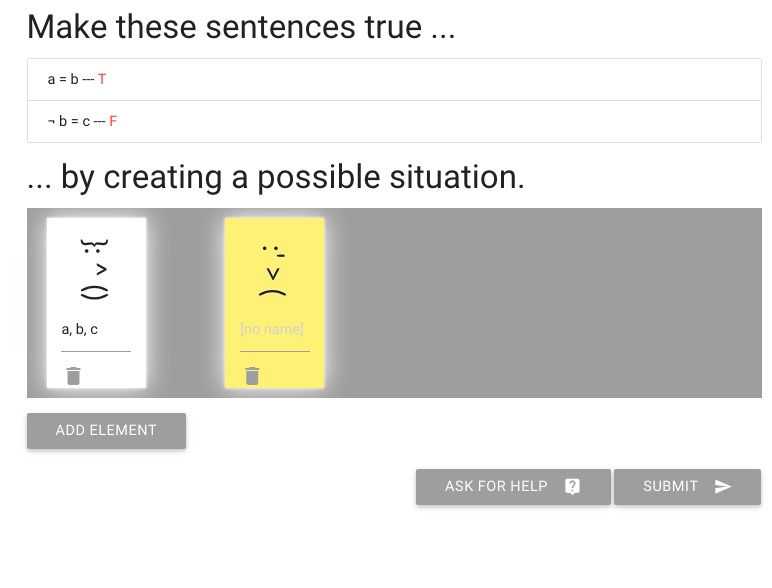

So here you see one person has all three names

Of course this means the second sentence, ‘not b=c’ is false.

We need to make that true.

How are we going to do that?

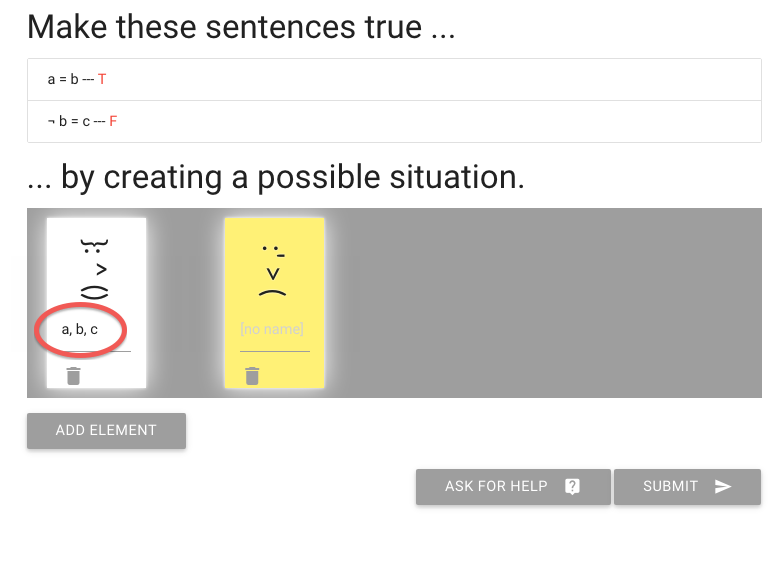

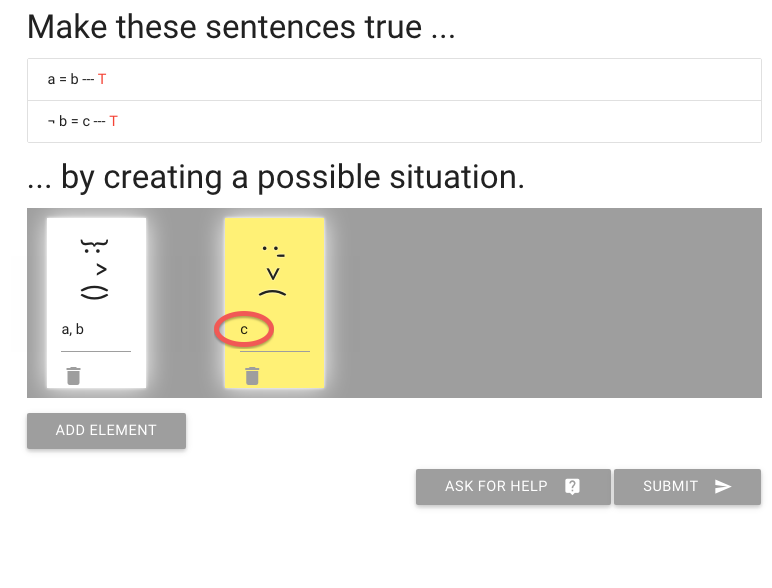

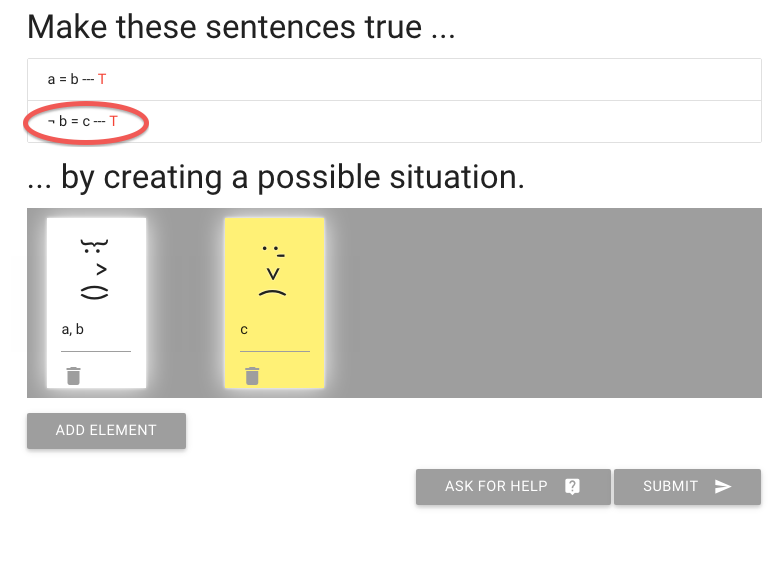

Let me re-arrange the names.

You see that I’ve named the other, yellow person c.

And this is enough to make the second sentence true.

2.5, 2.6