Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Truth Tables

Here's a rough guide to what the connectives mean.

Rough guide:

`$\land{}$' means and

`$\lor{}$' means or

`$\lnot{}$' means not

Why do we need more than this rough guide?

Consider the sentence 'I love logic or I love chocolate'.

If I were to say this to you, and it turned out that I loved logic and chocolate both,

you might think I had mislead you by saying 'or'. And that might lead you to think

that the English sentence is false, and that 'or' sentences are false when the two sentences

they conjoin are both true. That is, the English 'or' is exclusive.

But now consider a different example. You say to me, 'You can be my friend if you love logic or chocolate'.

Then, as before, it turns out that I love both.

In this situation you're not going to deny me friendship. You're not going to say I haven't meet the criterion you specified.

No, if I love both then I'm doubly your friend.

This tells us that an English sentence involving 'or' is true when the two sentences

conjoined are both true. That is, the English 'or' is inclusive.

But now we seems to have contradictory urges. One case urges us to say that the English 'or' is exclusive

(false when the things conjoined are both true), the other case urges us to say the opposite.

Now the truth is probably that the English 'or' is neither inclusive nor exclusive but much more complex still.

The point of introducing a formal language is to avoid all this complexity.

Not because there's anything wrong with the English 'or'--on the contrary, it's complexity is a wonderful thing for communication.

But our concern is not communication but logic.

Now if we define our symbols just by invoking the meanings of English words, we won't succeed in avoiding the complexity of

natural languages like English. We will have merely replaced one sign with another.

This is why we need more than the rough guide

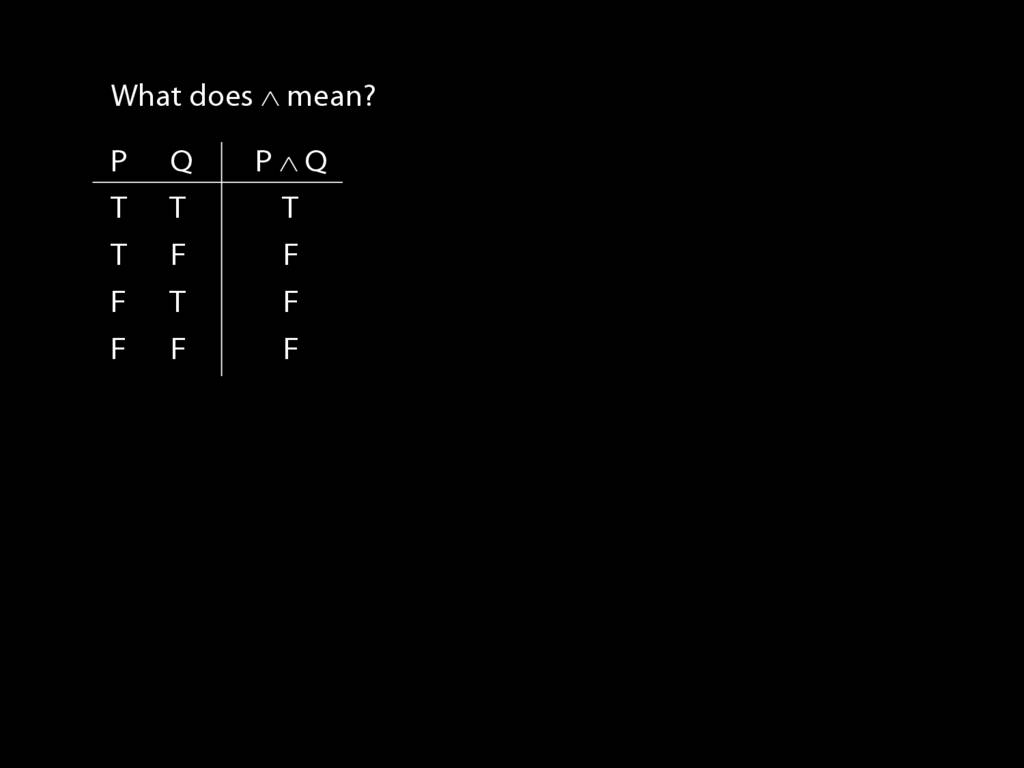

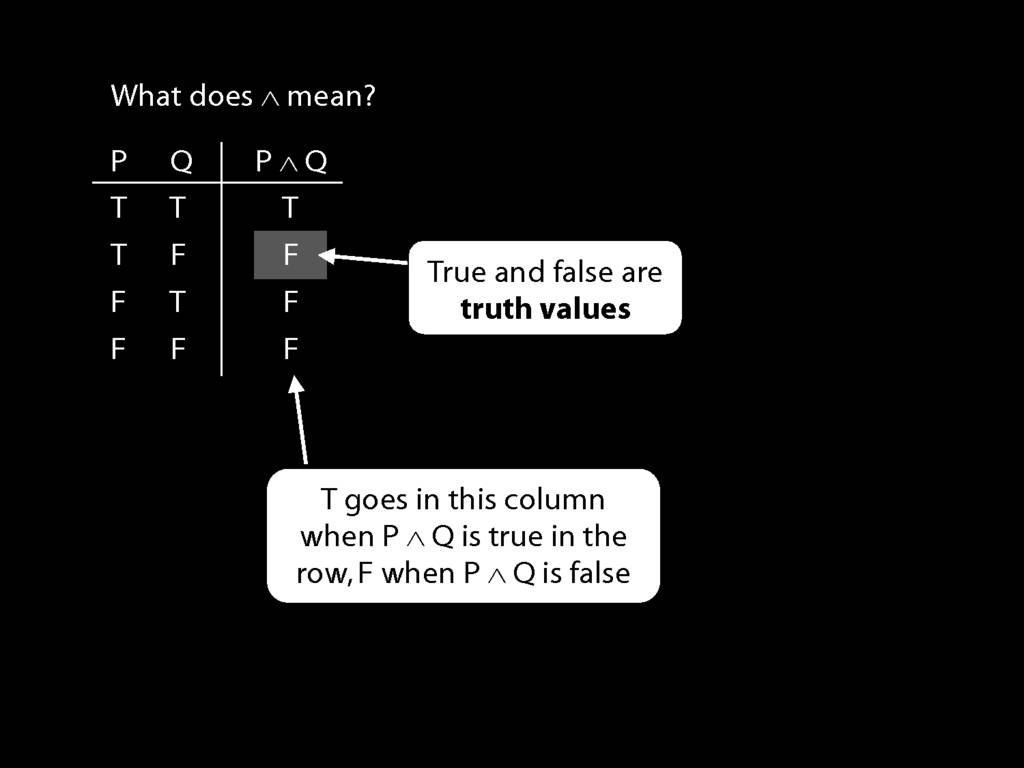

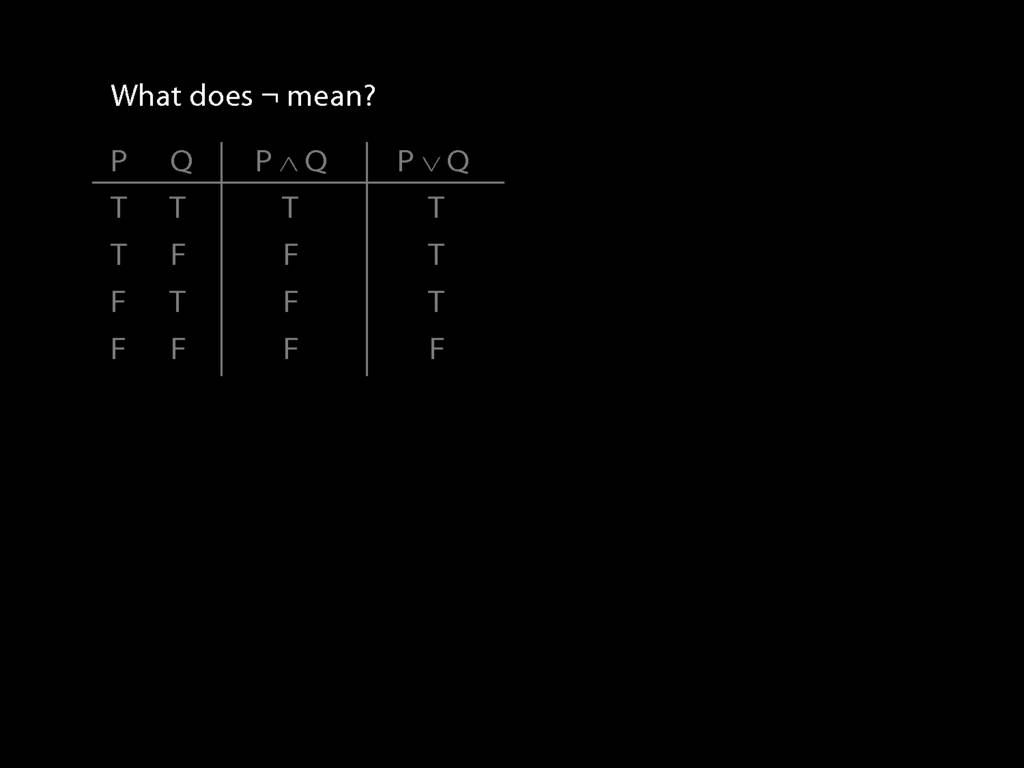

So what does a symbol like ∧ mean?

The answer is given by a truth table.

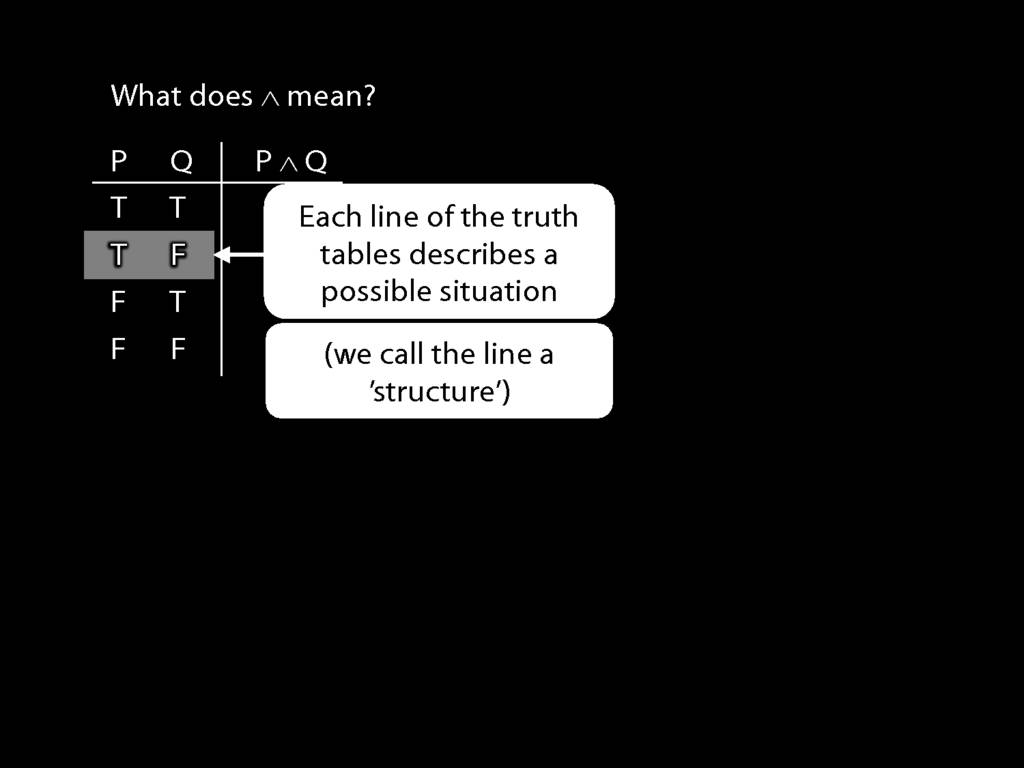

Each line of the truth table describes a possible situation.

For instance, this line of the truth-table describes the situation where P is true and Q false.

(Strictly speaking, this is not a possible situation but a whole class of possible situations.)

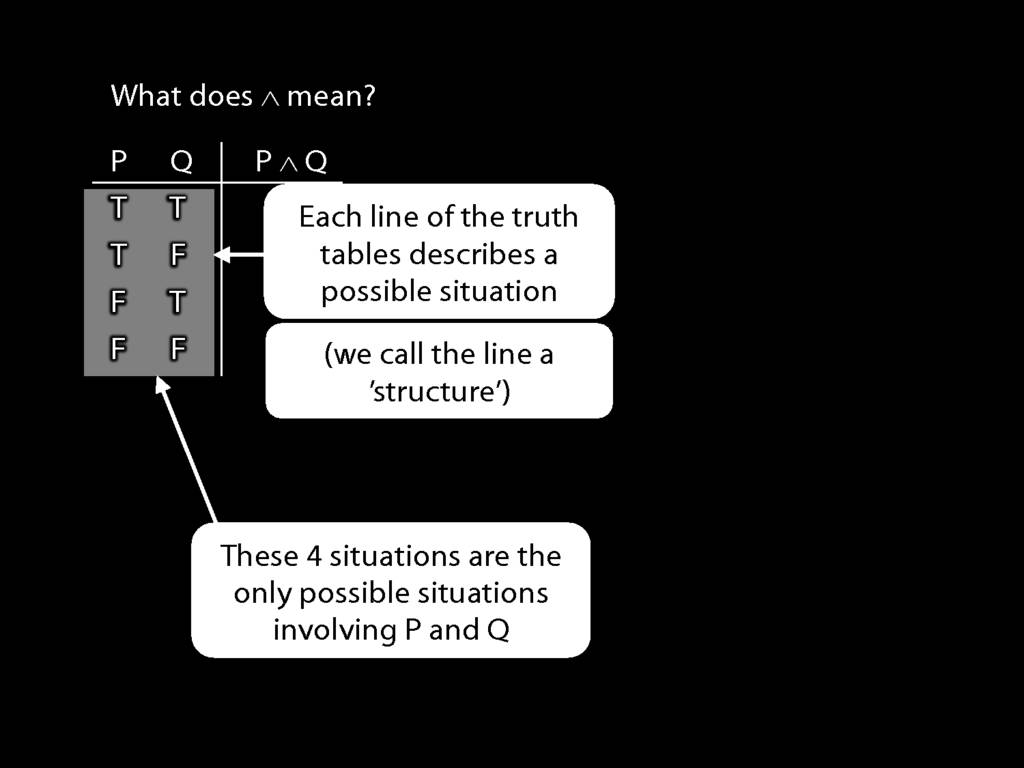

Insofar as we are interested in sentences involving sentence-letters and certain connectives,

we need only distinguish possible situations in which the sentence-letters of interest have different truth values.

This means that if we are concerned with two sentence letters, there are only four kinds of possible situation that we

need to consider.

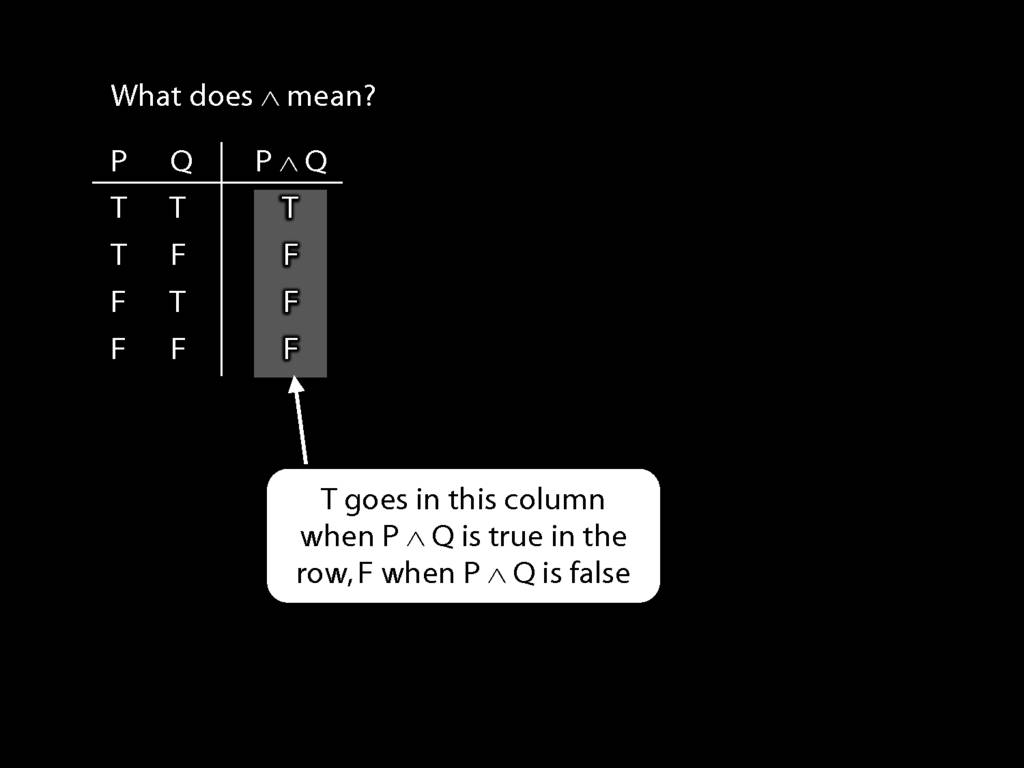

The Ts and Fs in this column tell us whether the sentence is true or false.

So, for example, we are told that P∧Q is false when P is true and Q false.

These true and false are called truth-values.

To illustrate, suppose I ask you, What is the truth-value of P∧Q in this row (the second row)? What would you say?

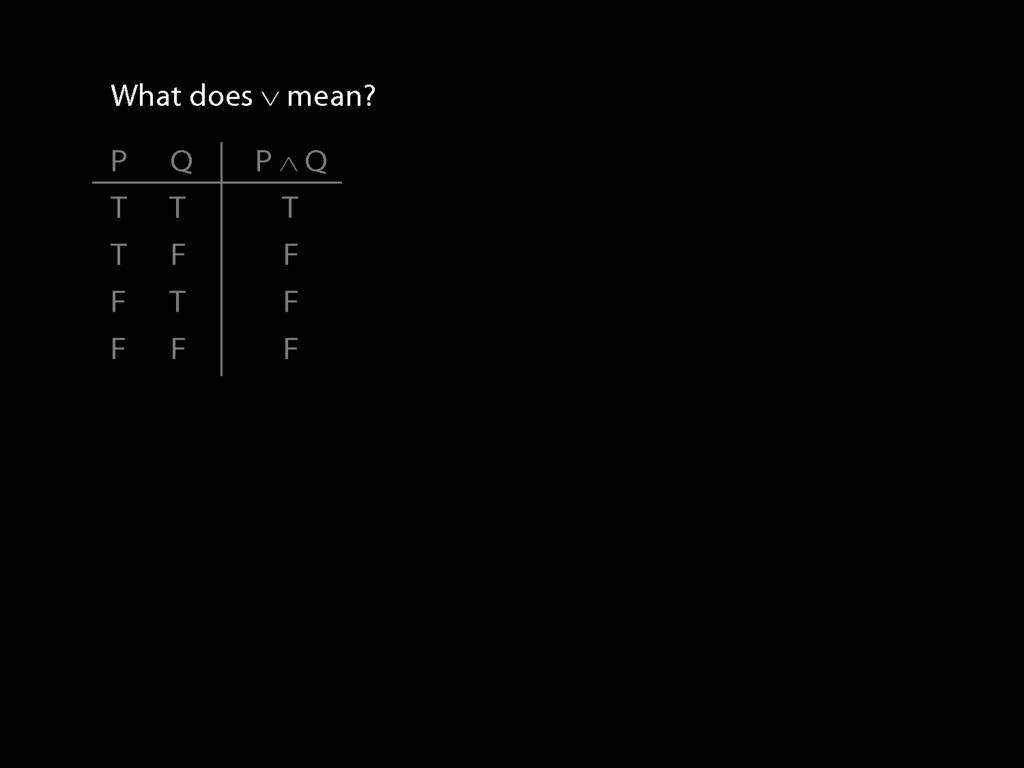

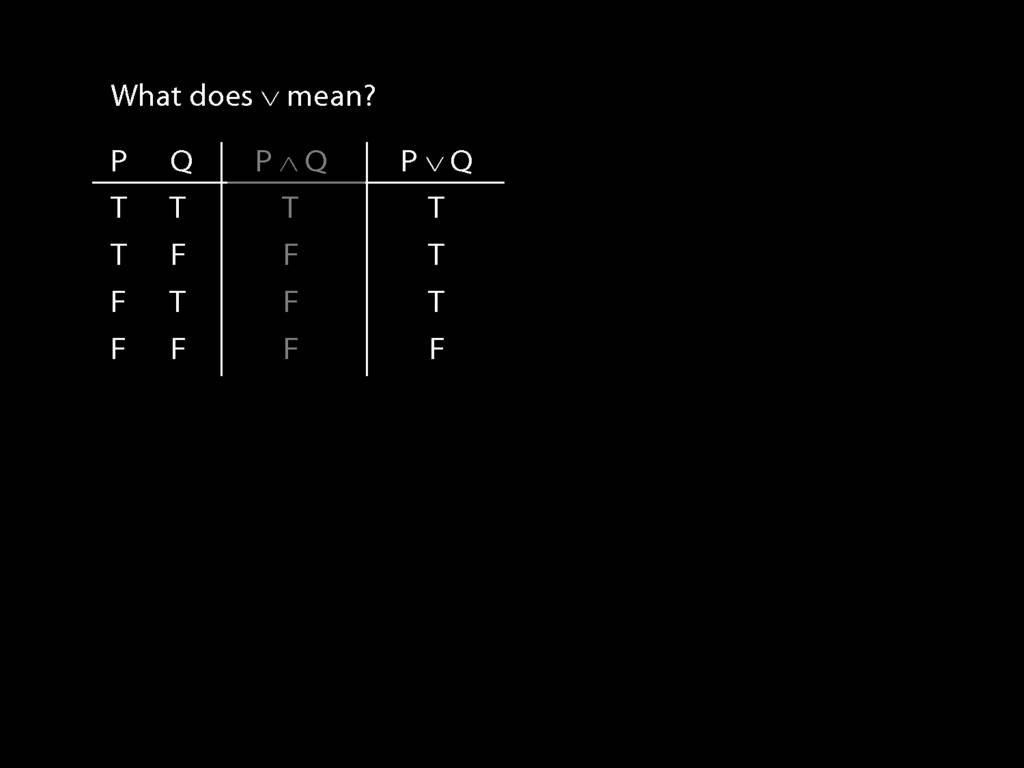

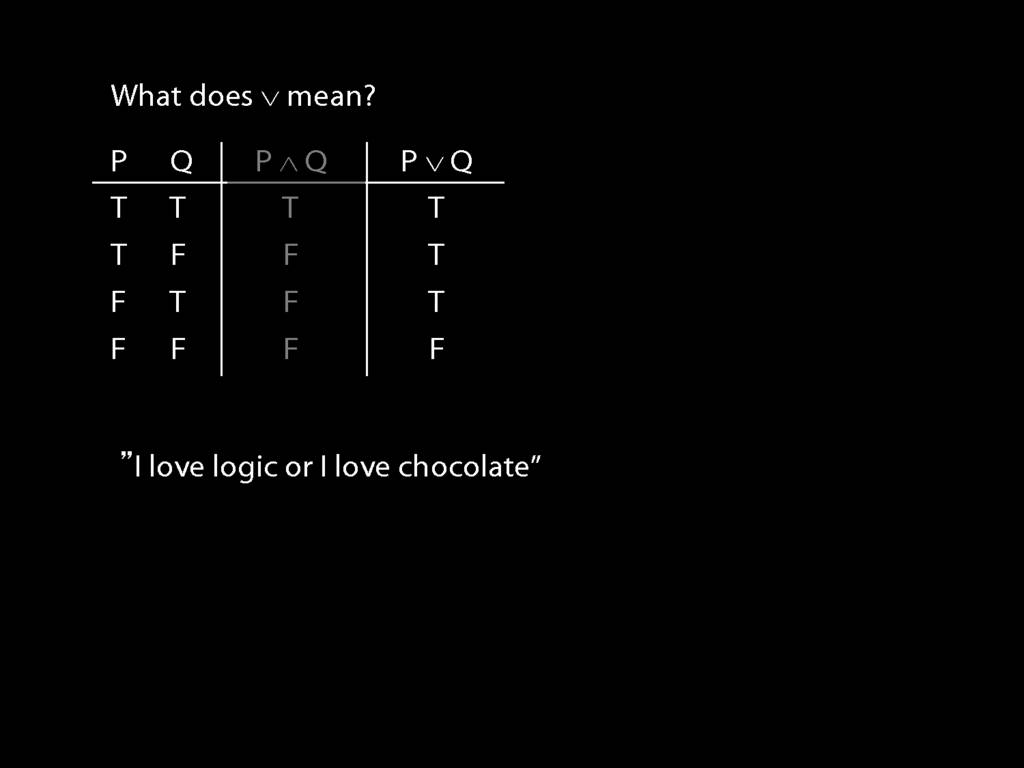

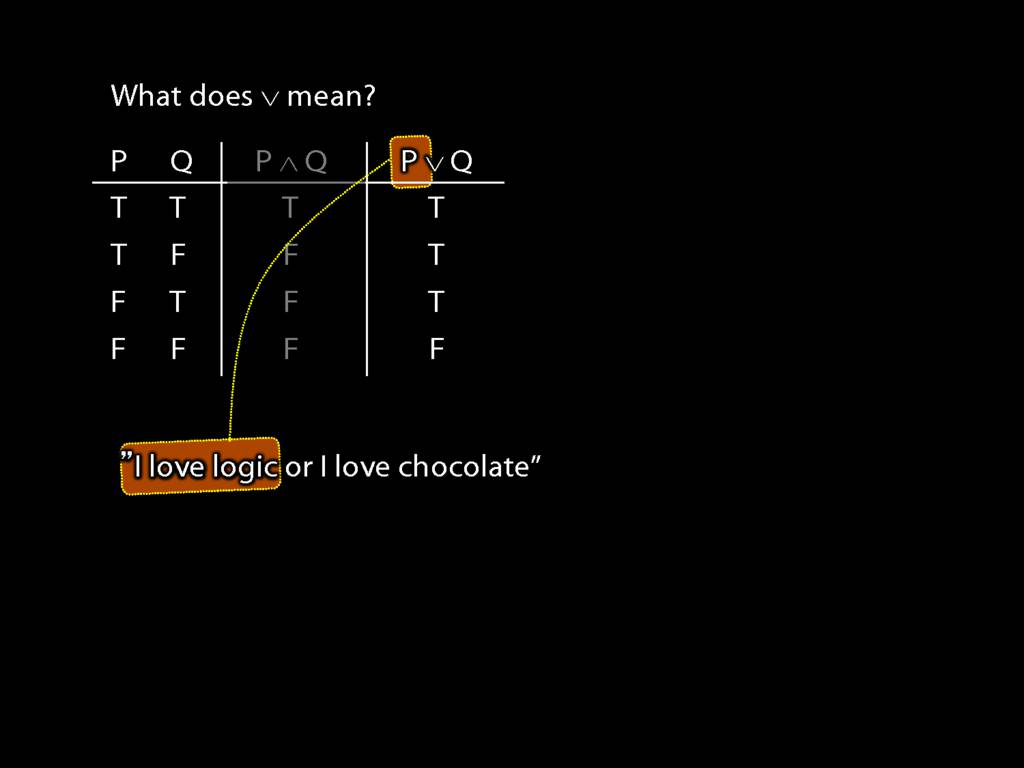

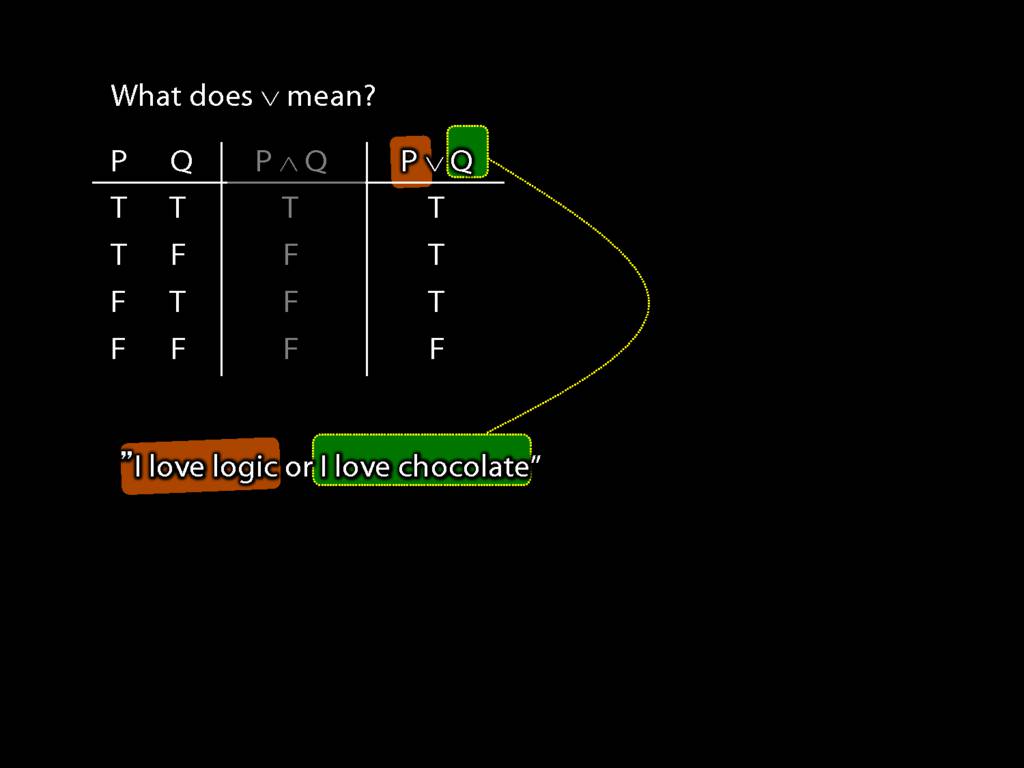

What does ∨ mean?

The answer is given by another truth table.

Let's return to the English sentence about loving chocolate or logic.

Imagine that instead of 'or' we had the logical symbol for disjunction, ∨.

Then 'I love logic' is P, and ...

... 'I love chocolate' is Q.

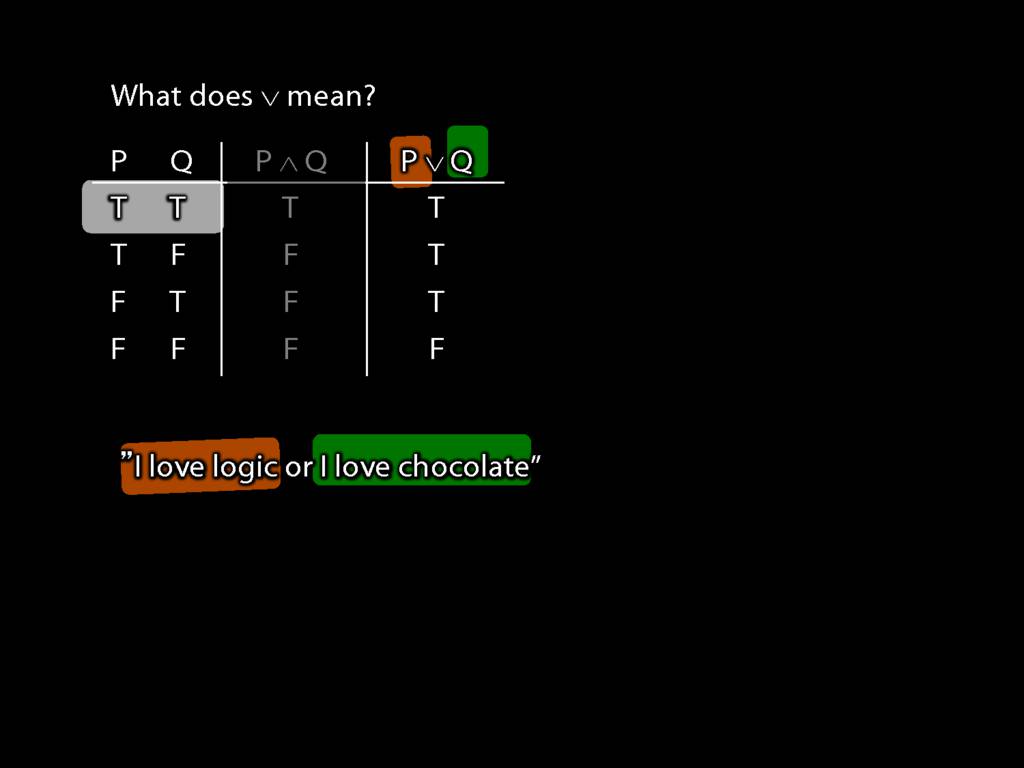

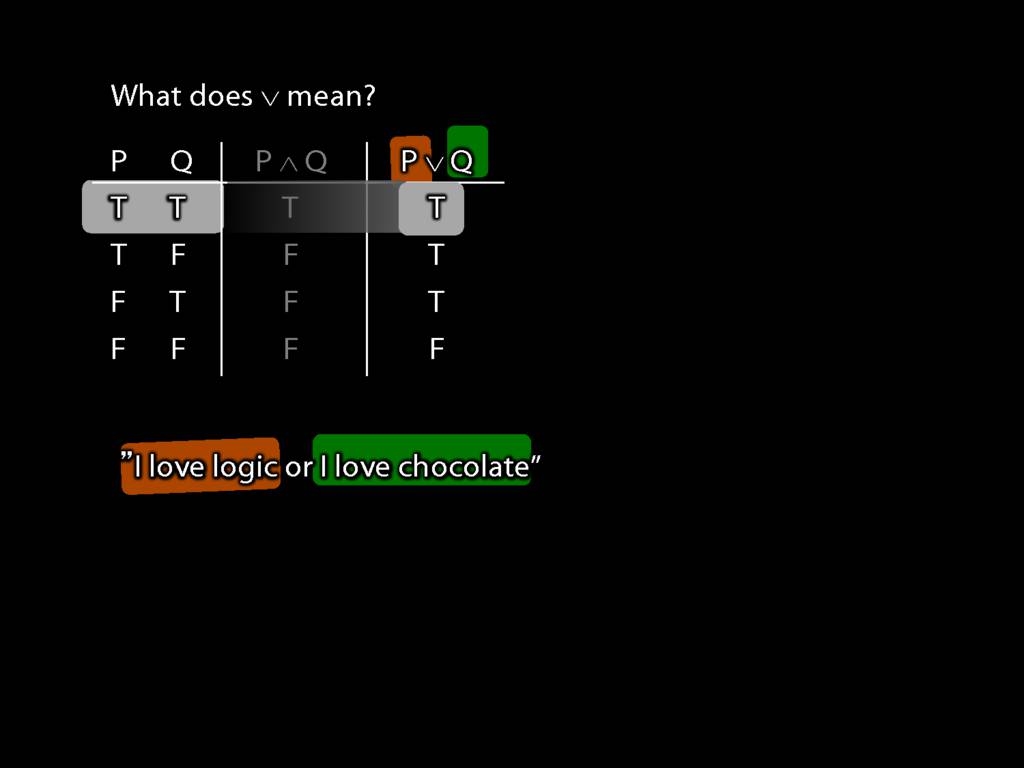

Now what happens if they are both true?

The truth-table tells us that their disjunction is also true.

So specifying meanings by invoking truth-tables means we don't have to worry about

the complexities of natural languages like English.

Note that the truth-tables are stipulations.

You can't argue that it is wrong to put a T in the first row of this truth-table.

The truth-table is a stipulation about the meanings of the symbol.

The point of a formal language is that it is a thing of our creation.

We are free to make whatever stipulations we like about it.

By contrast, we can't make stipulations about a natural language like English,

because natural languages have lives of their own.

In the case of natural language, meaning has to be discovered, not stipulated.

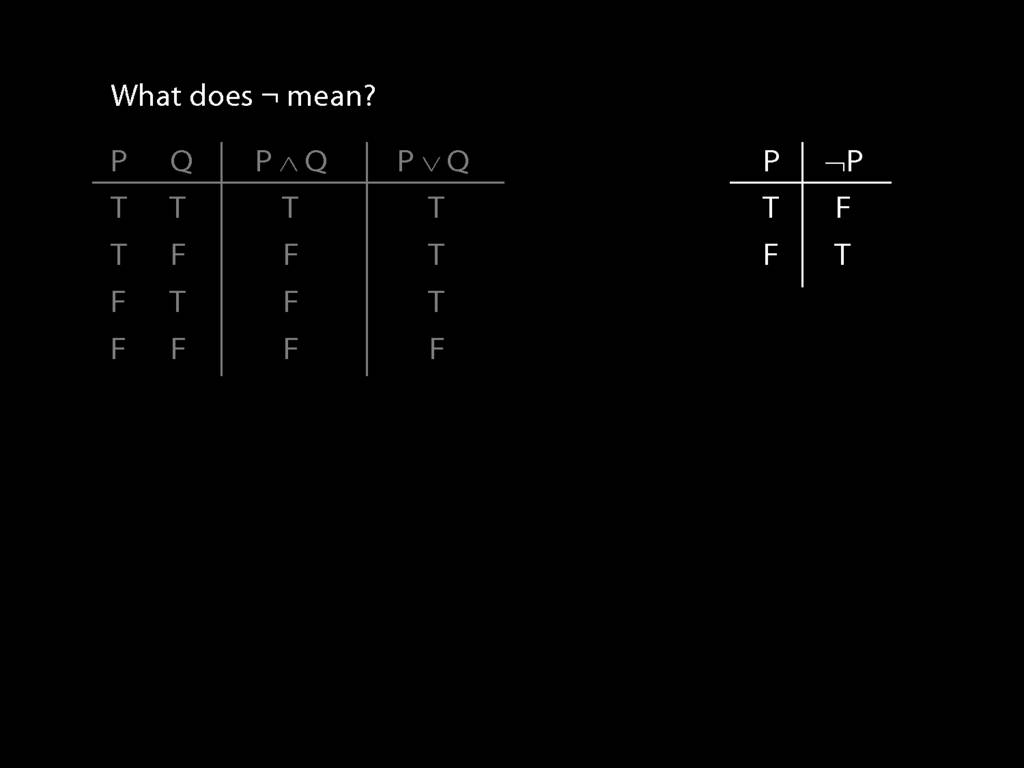

Finally, what do we say about the meaning of our symbol for negation, ¬?

The truth-table specifying its meaning is very simple; it takes true to false and false to true.

3.1, 3.2

3.5, 3.7

3.1, 3.3

3.5, 3.7