Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

∃Intro

Although this is about the rule ∃Intro, I want to start by revising universal elimination.

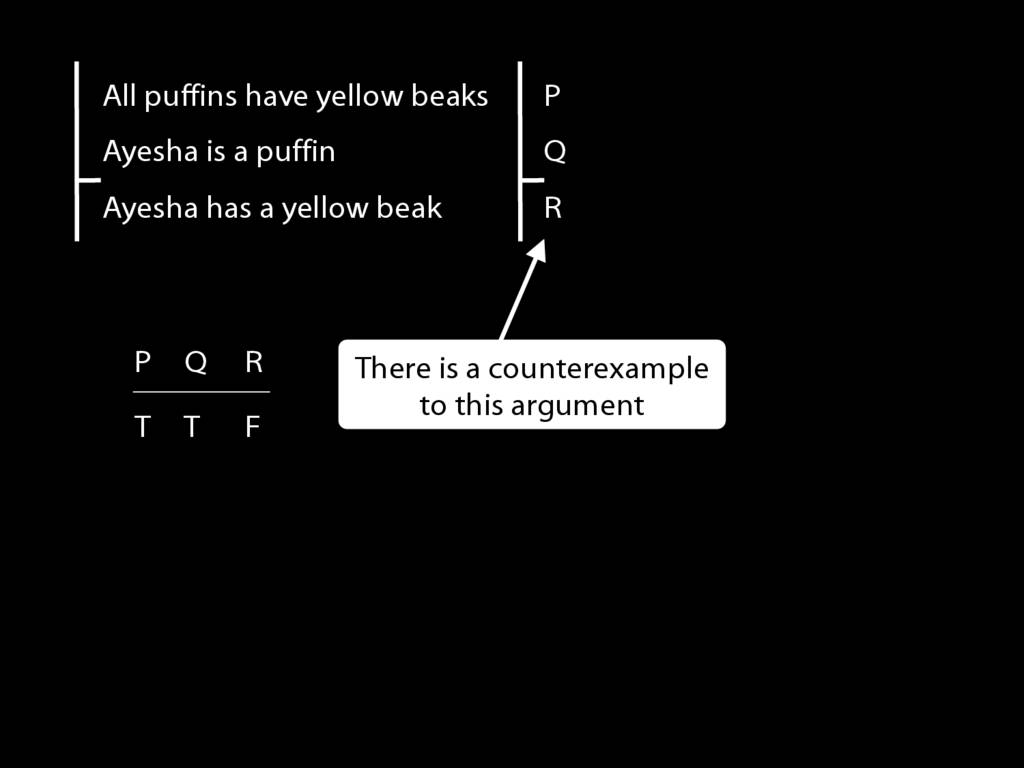

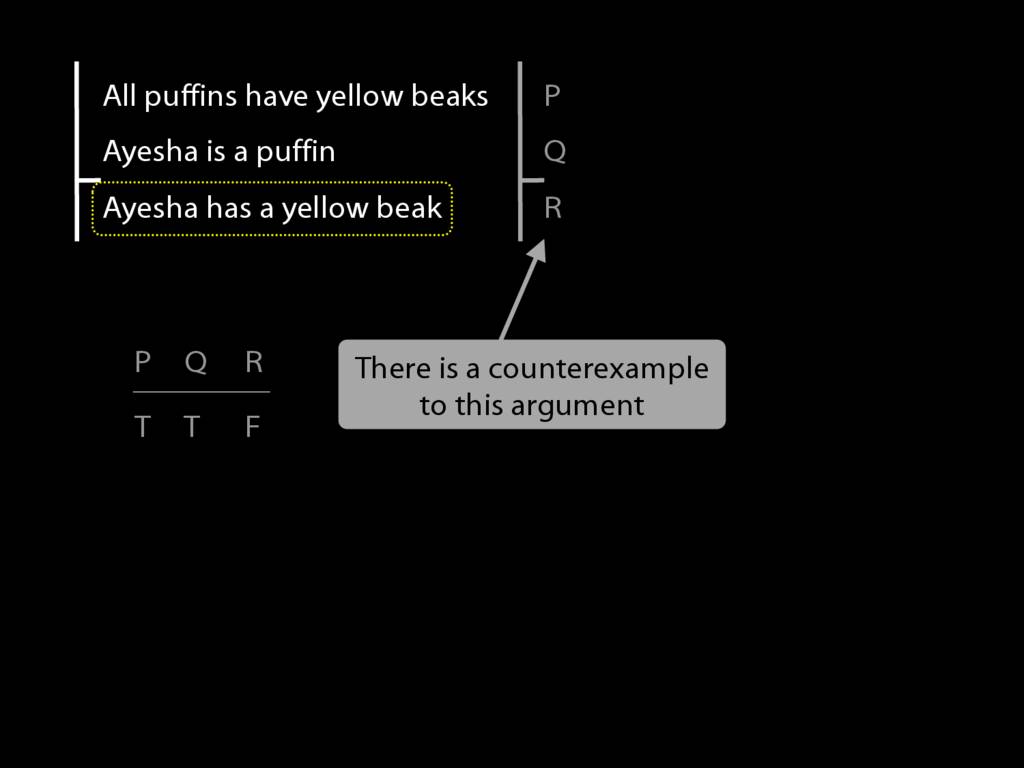

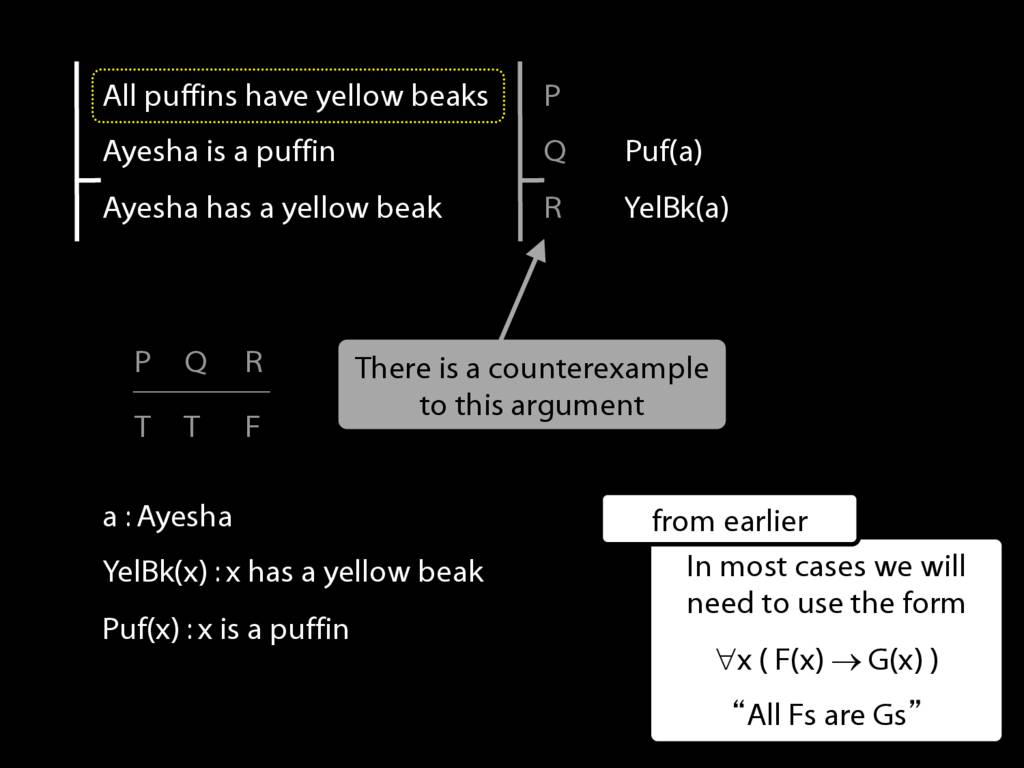

Consider this argument. Actually it's not true that puffins have yellow beaks.

Well, there might be a bit of yellow,

but that's not what I'd call a yellow beak.

Anyway, back to the argument. How can we formalise it?

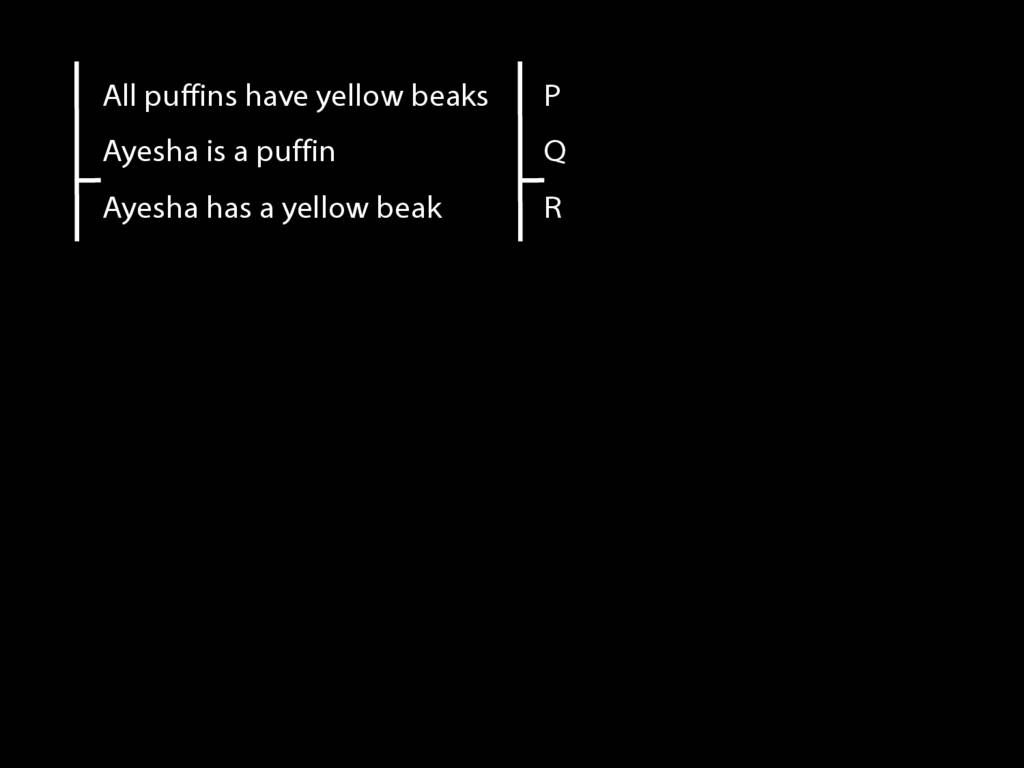

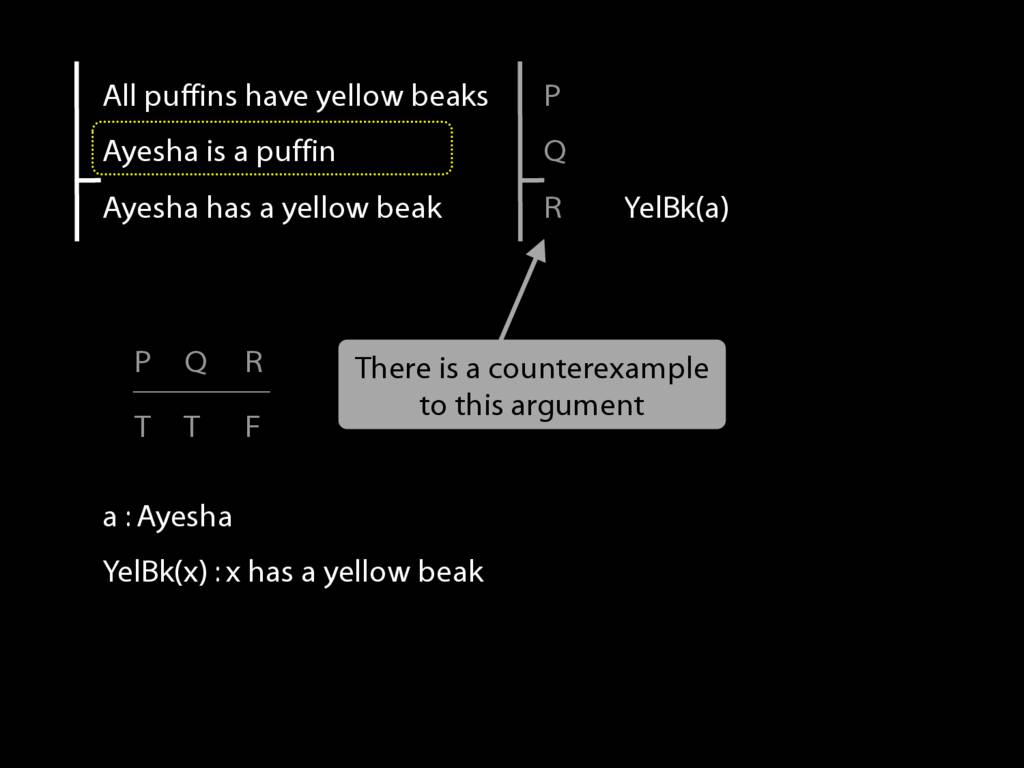

One approach would be to use sentence letters. Nothing wrong with this

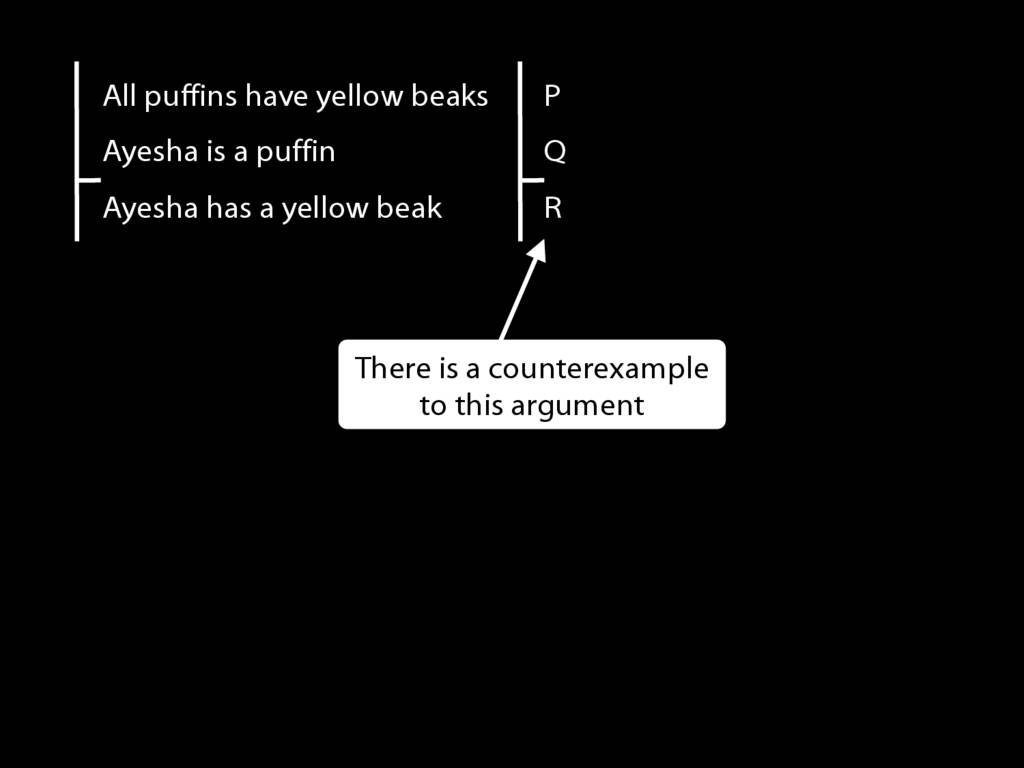

except that it doesn't capture the structure in virtue of which the argument is valid. There's a counterexample to this form.

Here it is. So how can we do better?

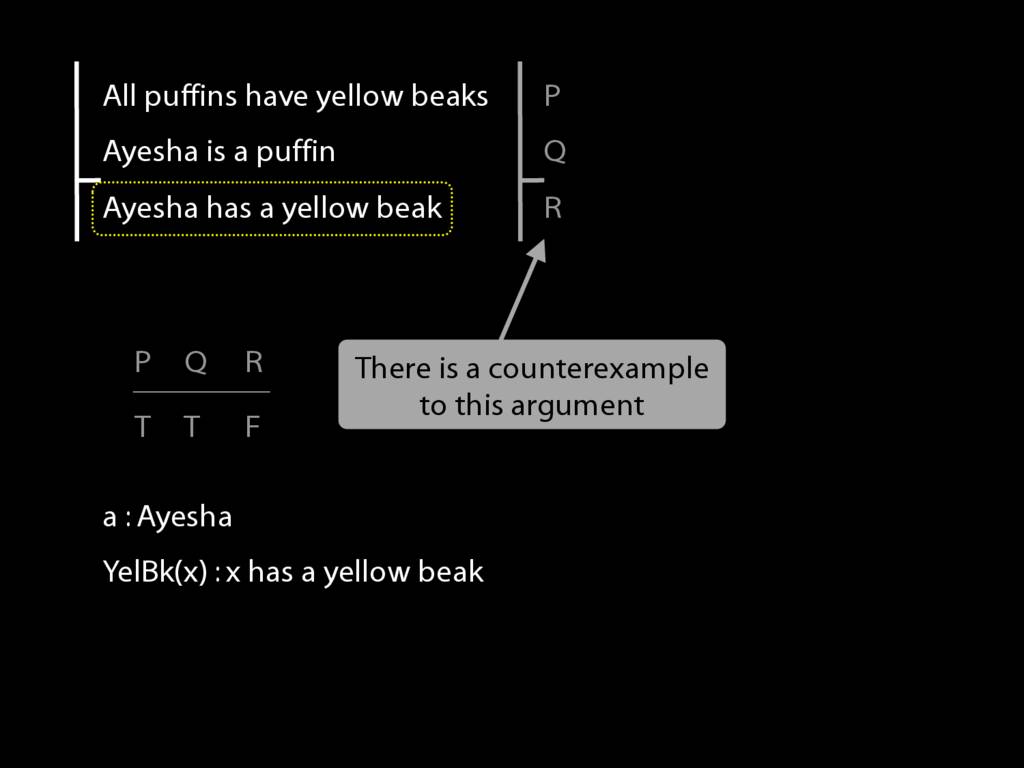

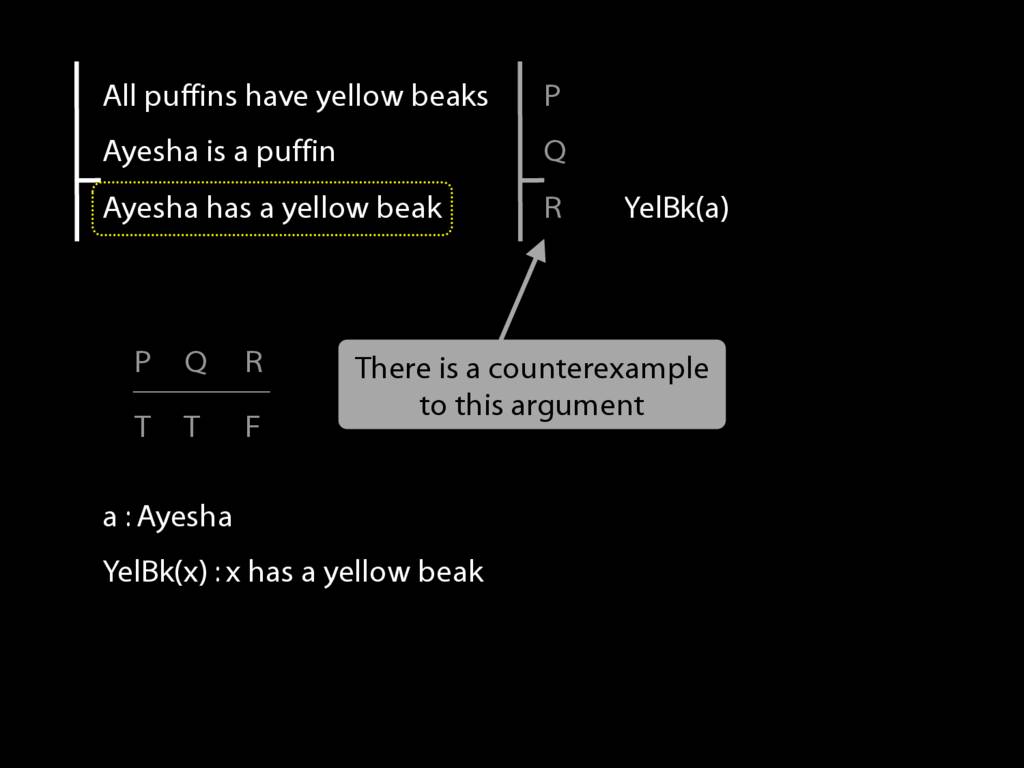

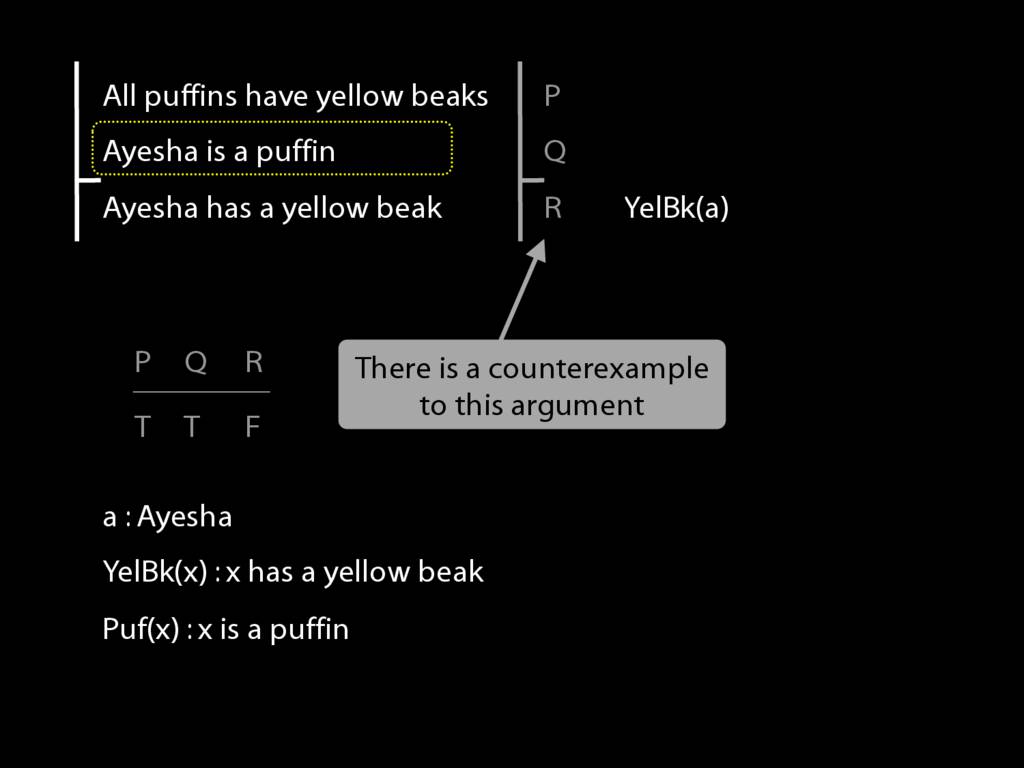

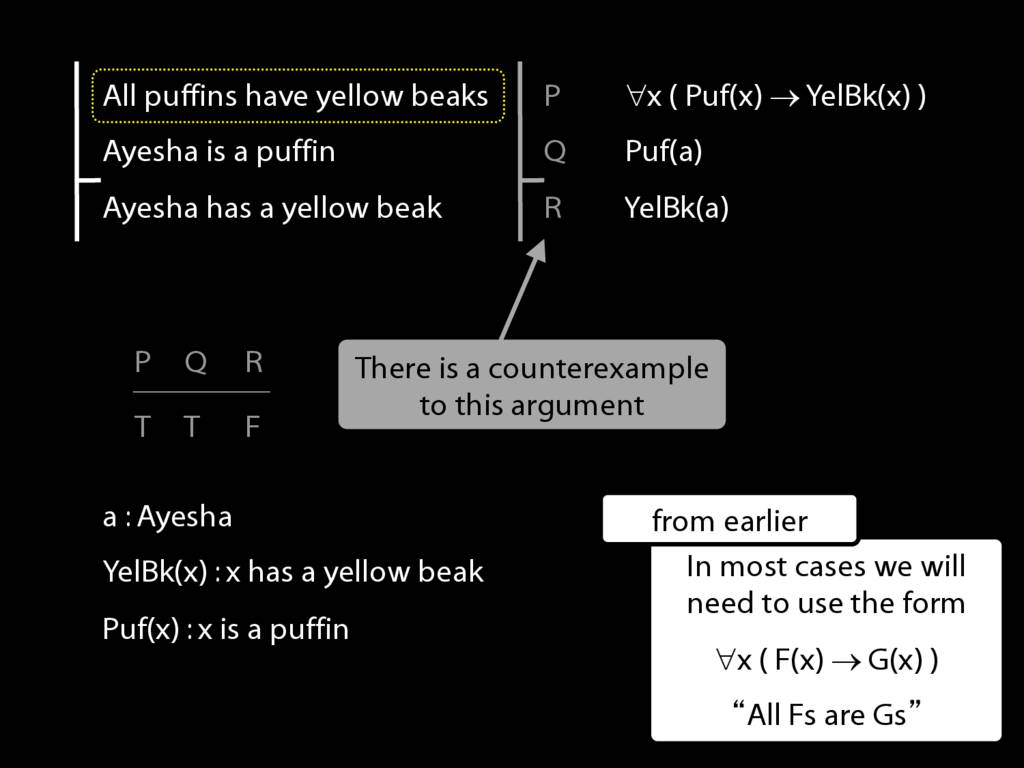

Start with the conclusion.

We need a name and a predicate.

These allow us to write the conclusion as 'YelBk(a)'. Easy, no? (It's supposed to be easy, we're just revising stuff.)

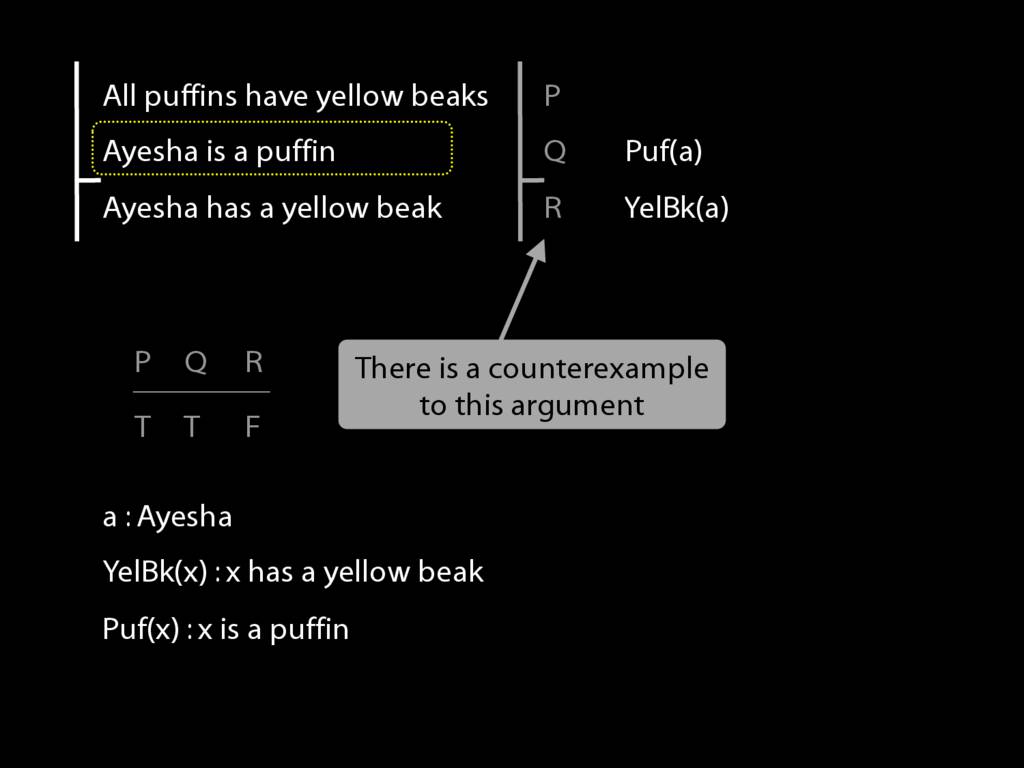

What about the second premise?

For this we need another predicate.

And then we can write this in awFOL as 'Puf(a)', Ayesha is a Puffin

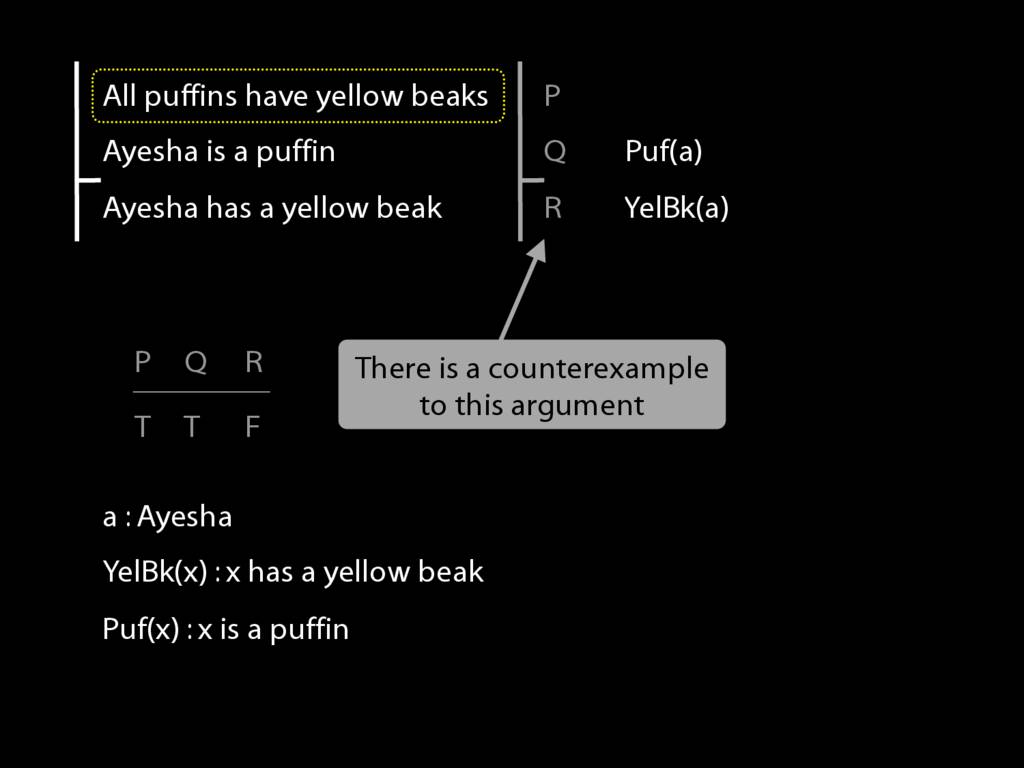

Finally, we have to formalise the first premise. How?

Well you know that, for universal sentences, we're always going to work from this example about all Fs are Gs.

So, well you know how it goes by now I hope.

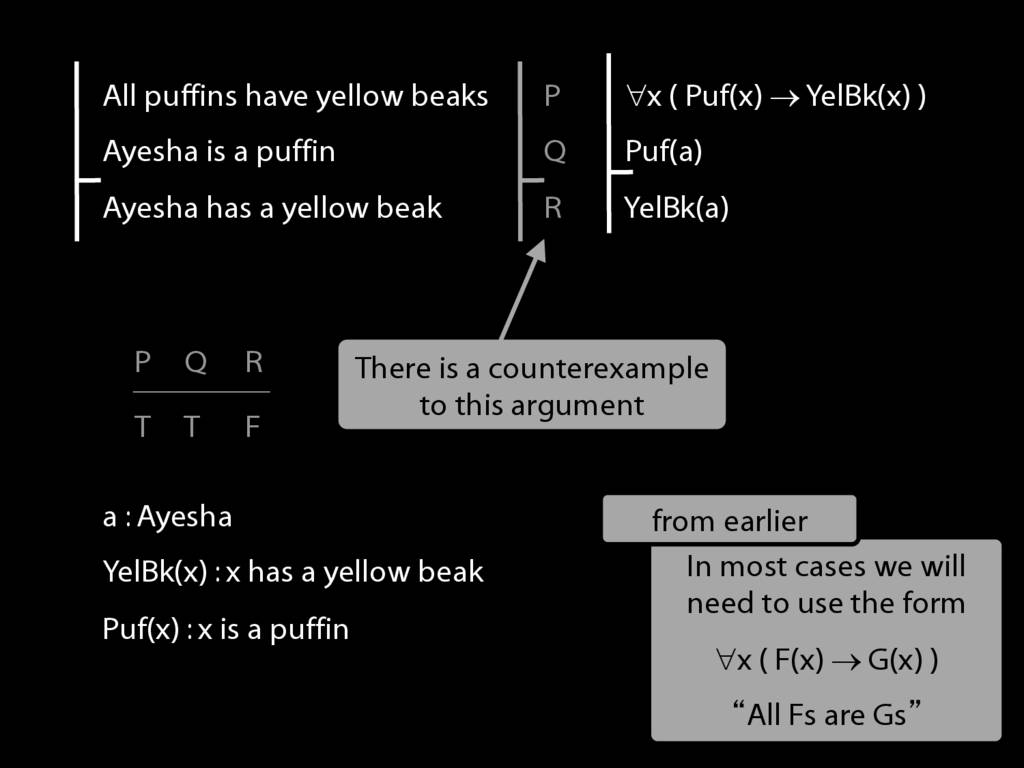

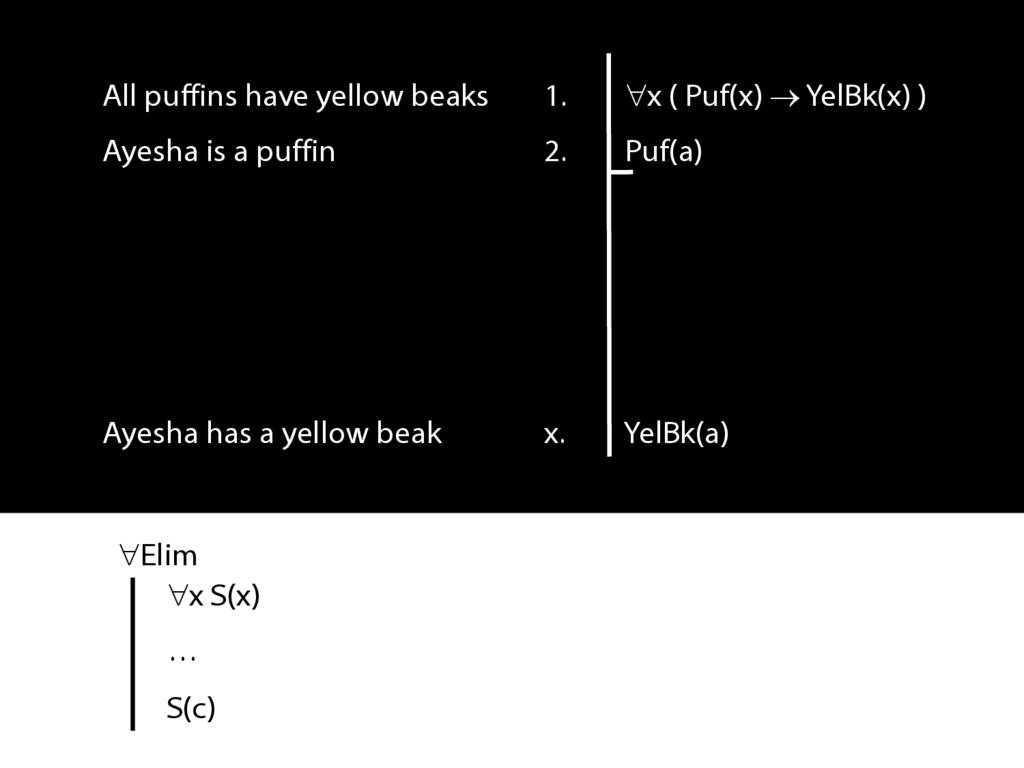

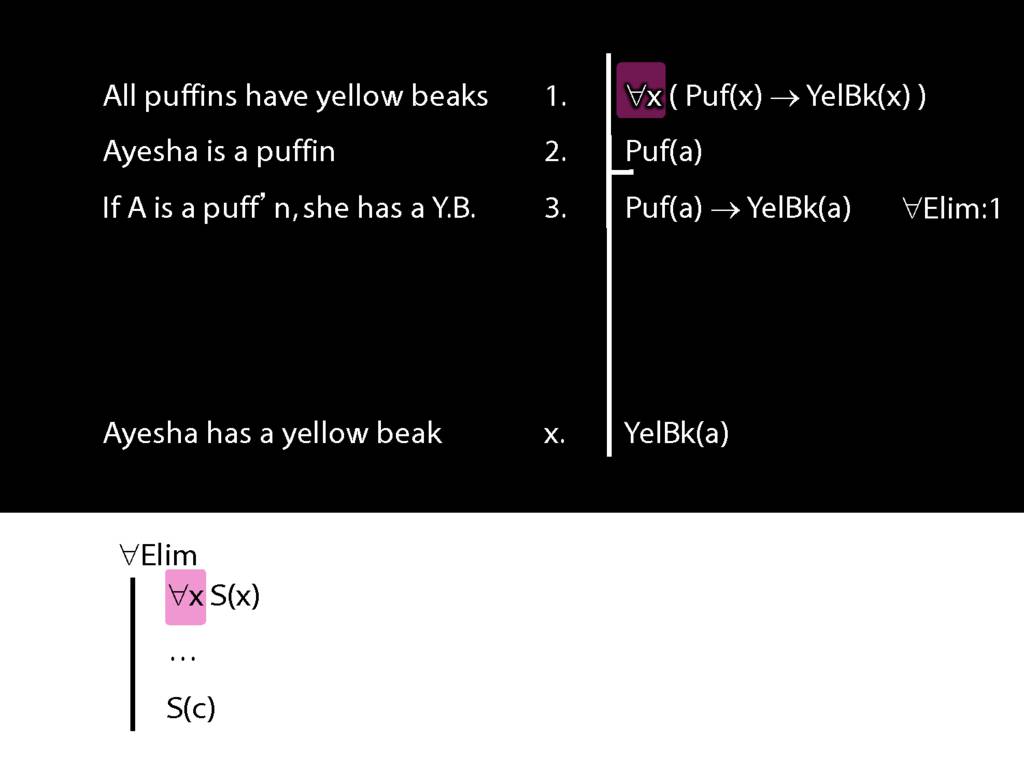

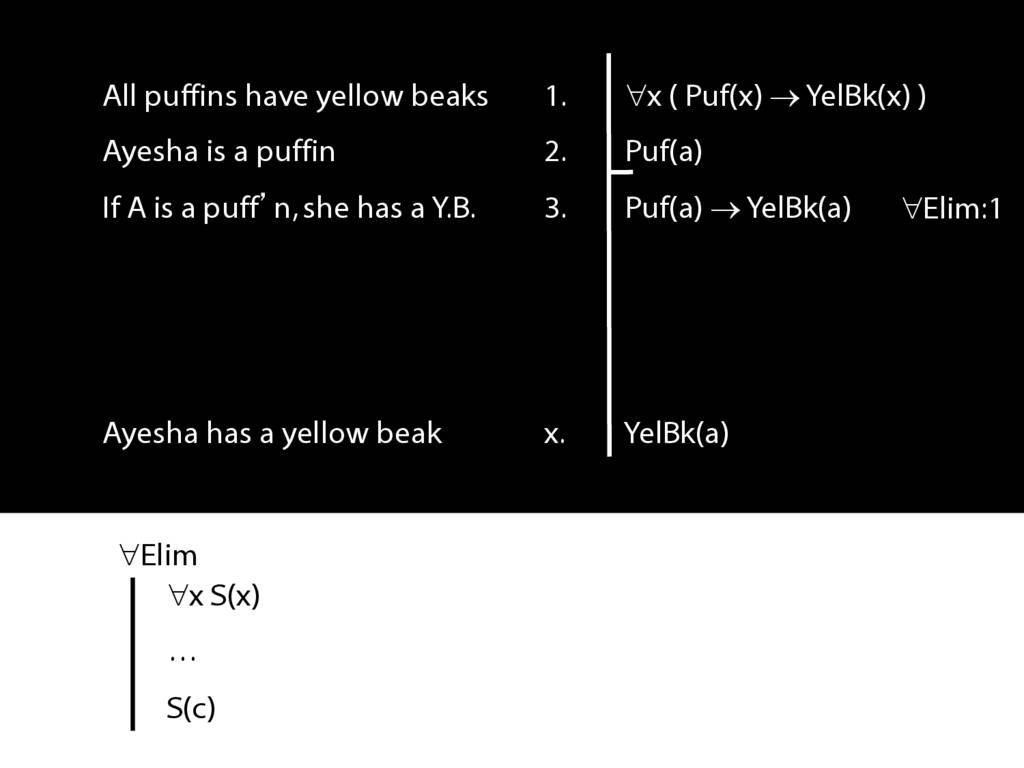

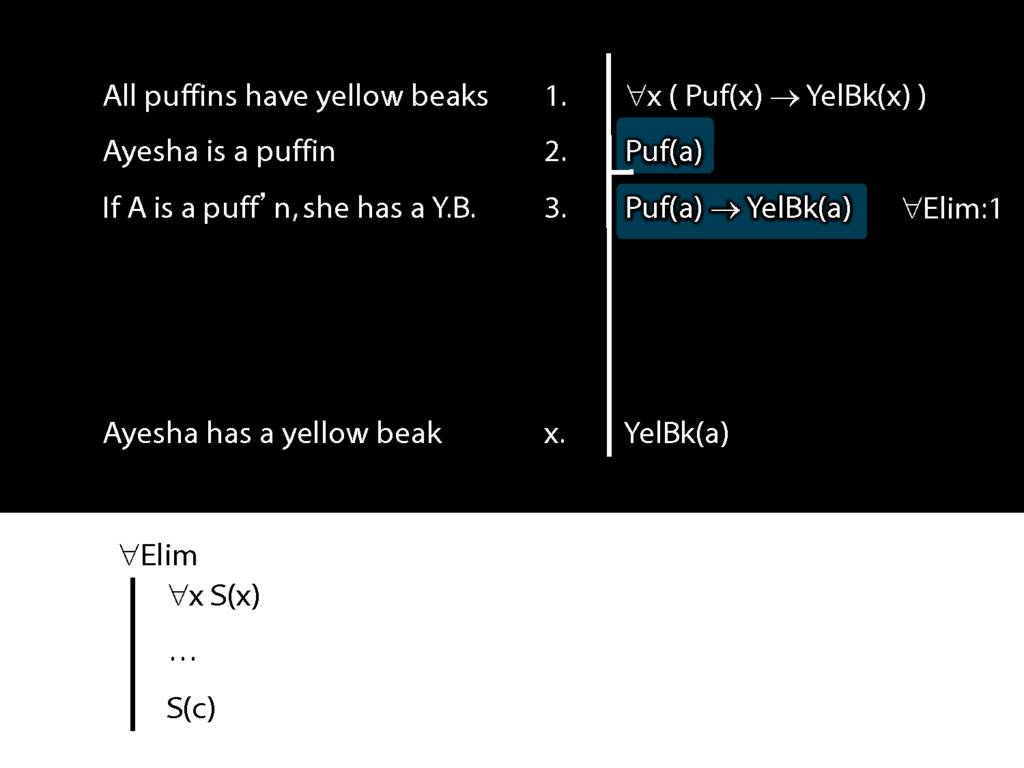

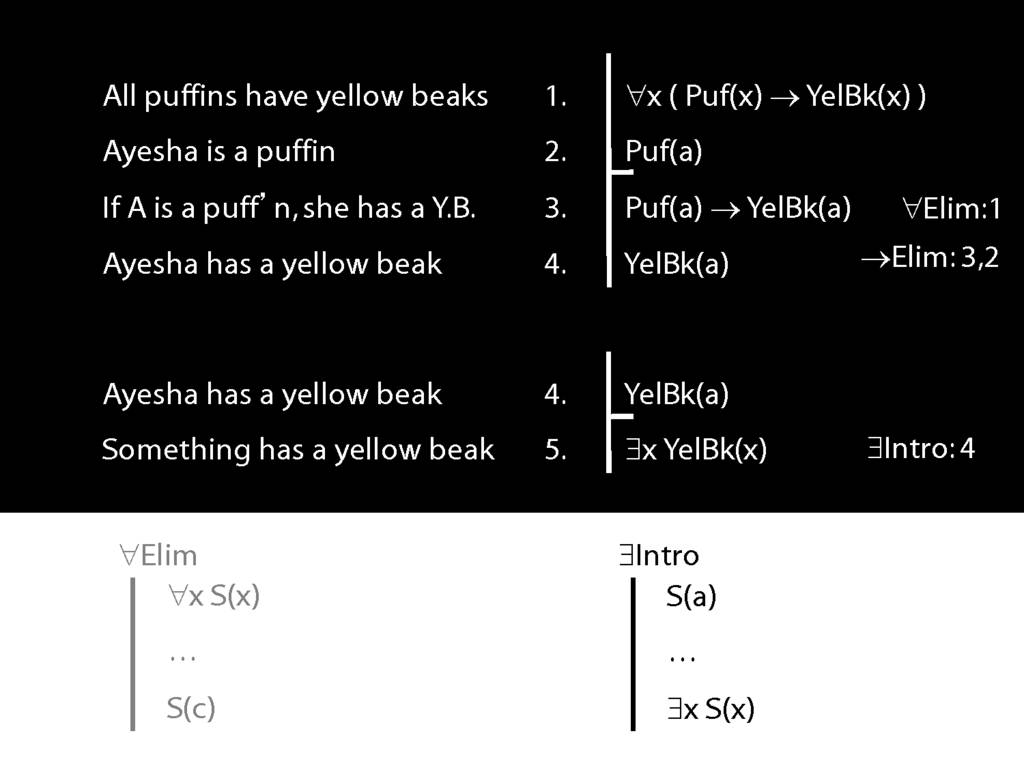

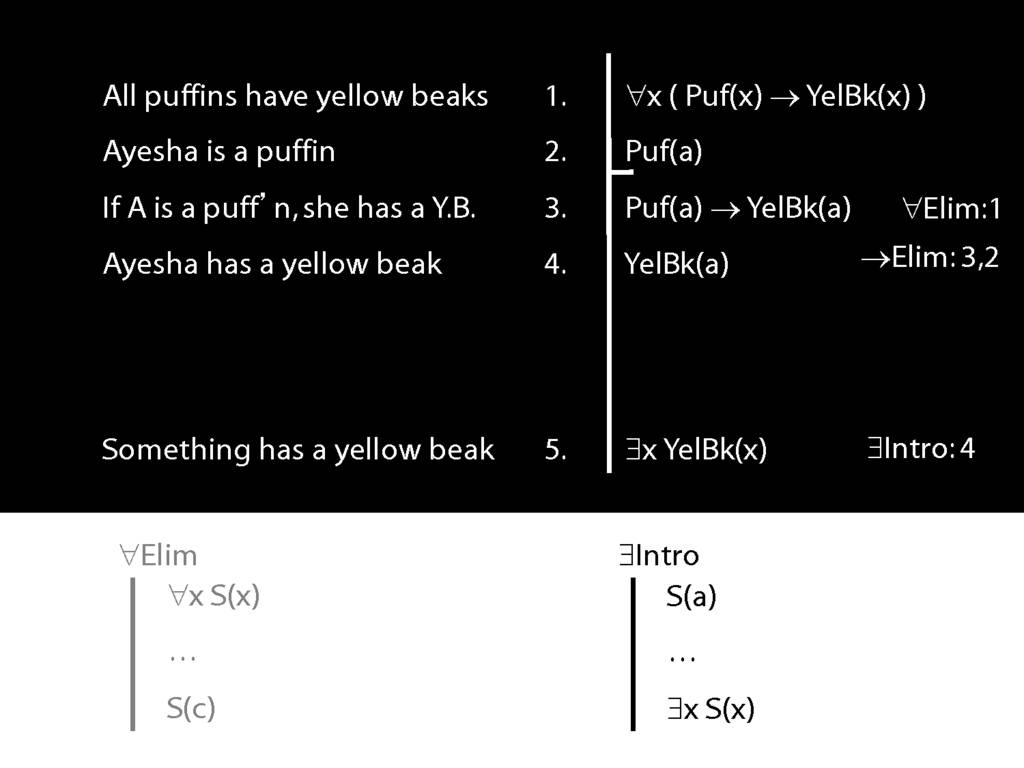

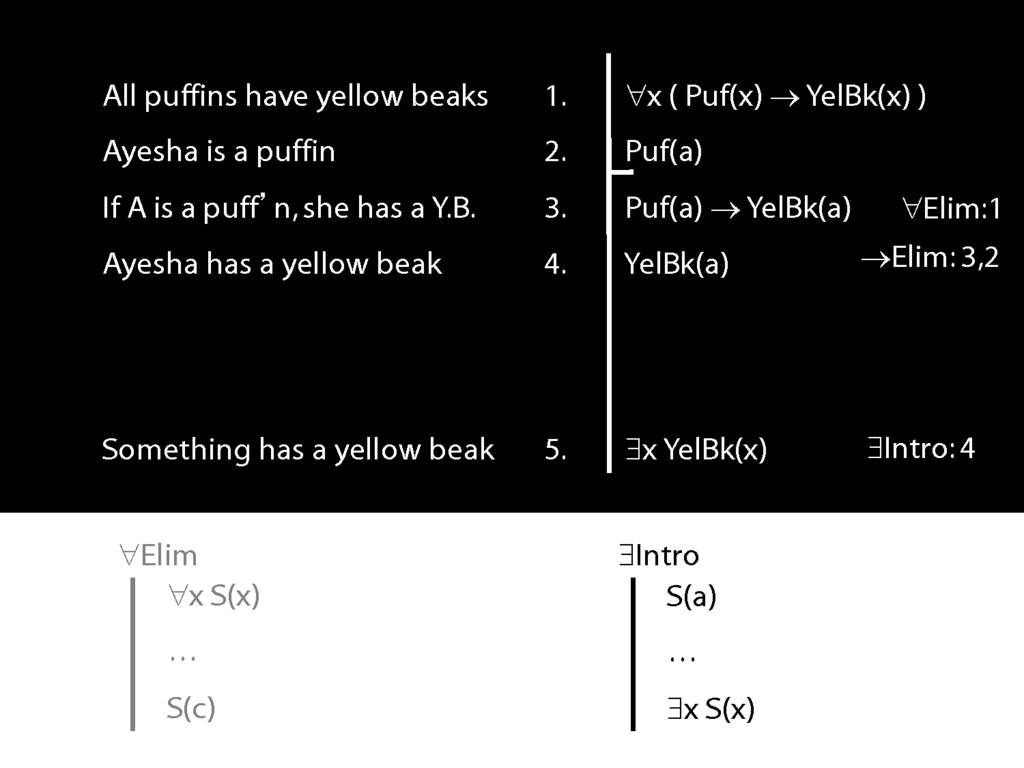

Now we have the argument translated into awFOL in such a way that the translation is logically valid too. Can we prove it?

Yes, we can.

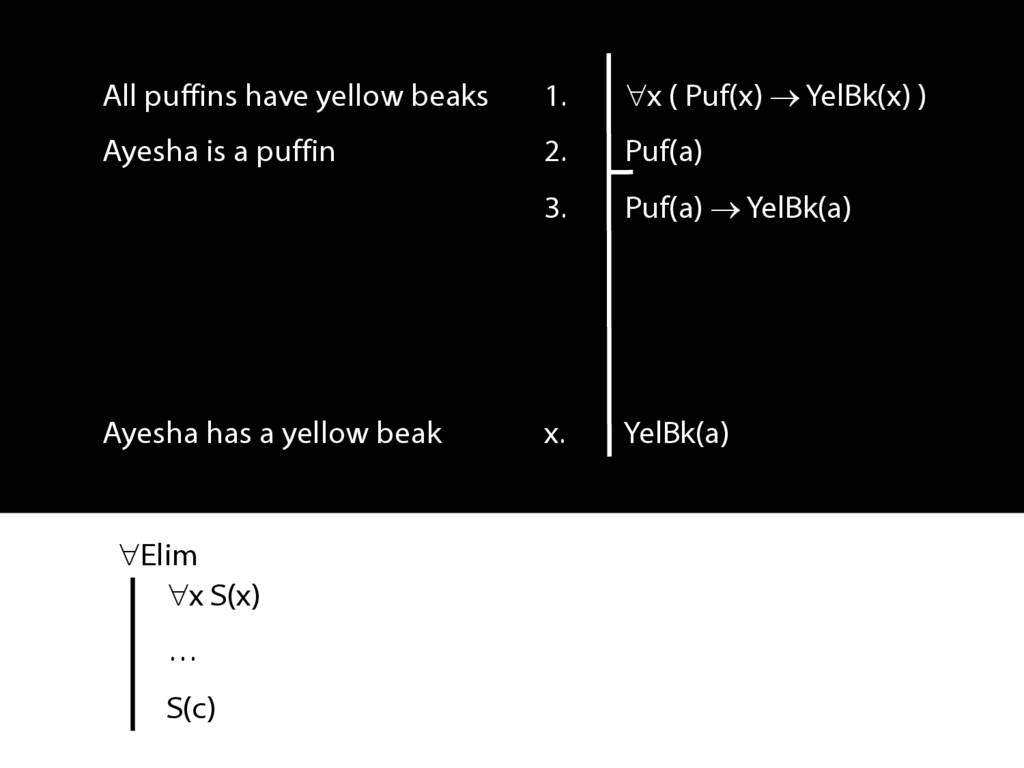

To this end, we need the rule we looked at at the end of last lecture, universal elim.

This allows us to infer that what is true of all things is true of Ayehsa in particular.

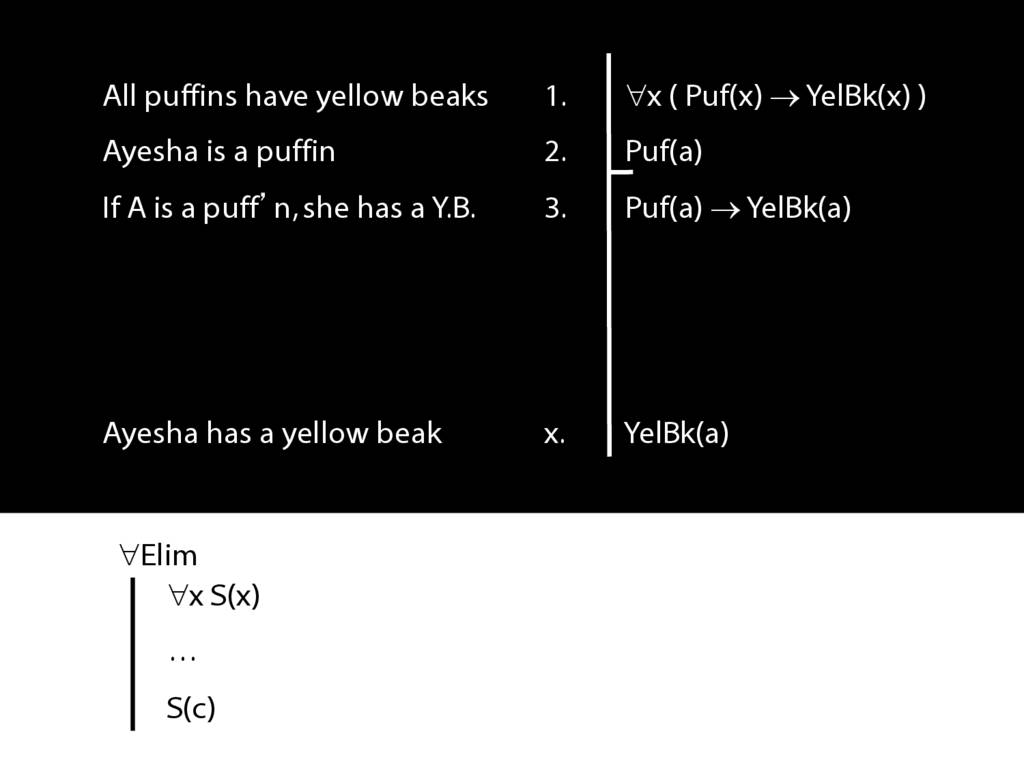

In English, If she's a puffin then she has a yellow beak.

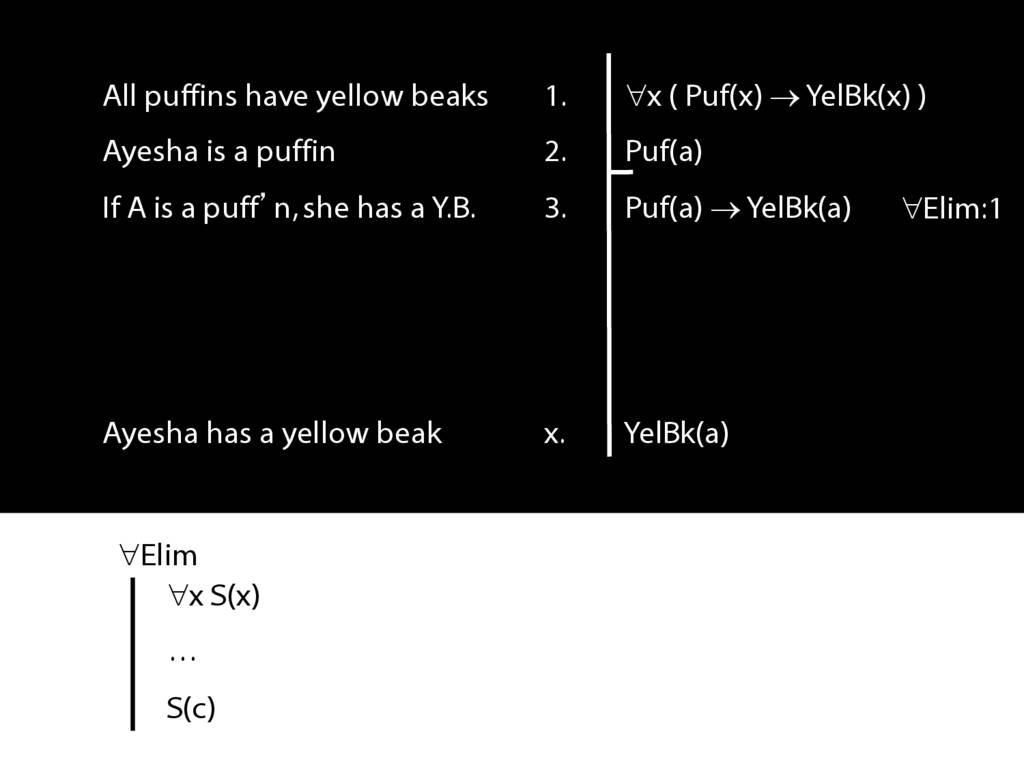

Of course we have to cite the rule we're using and the line we're applying it to.

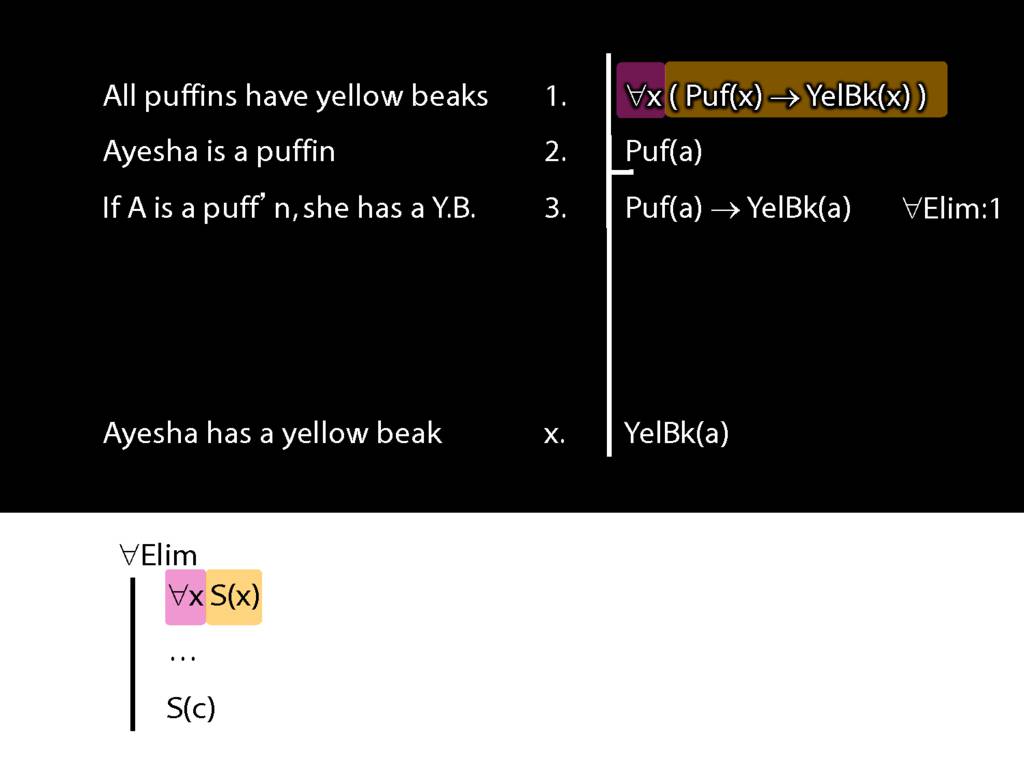

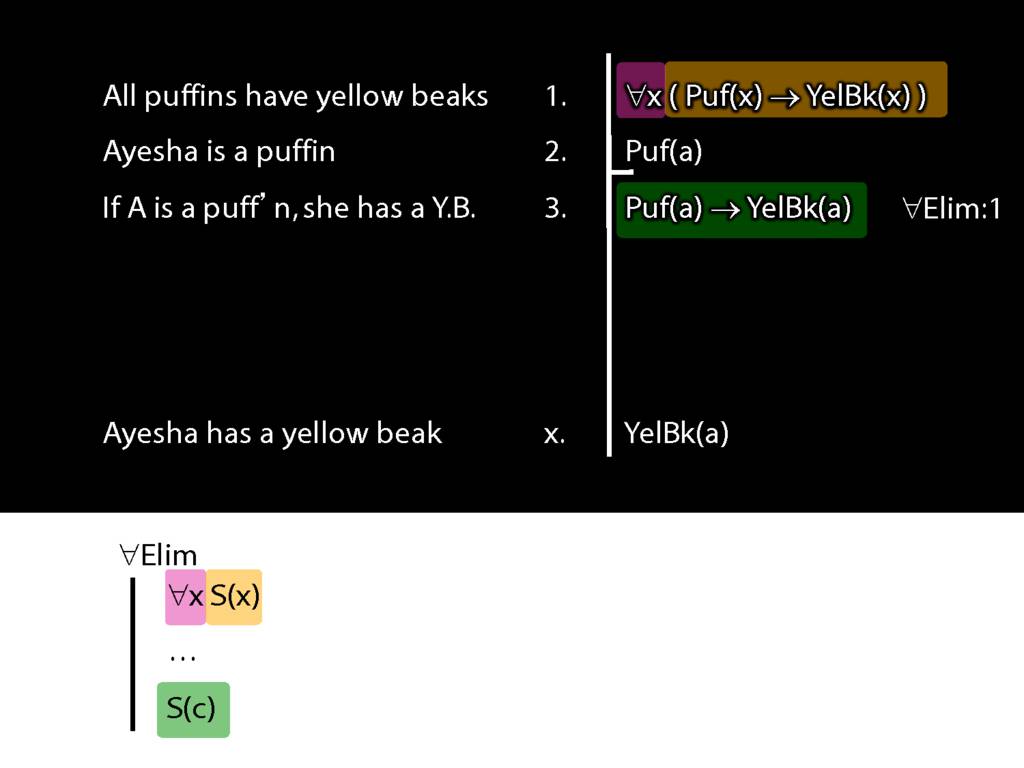

So you remember how universal-elim goes. We start with a universally quantified sentence ...

... universal something ...

... and we add the something to our proof, replacing the variable with whatever name we like.

Meraviglioso

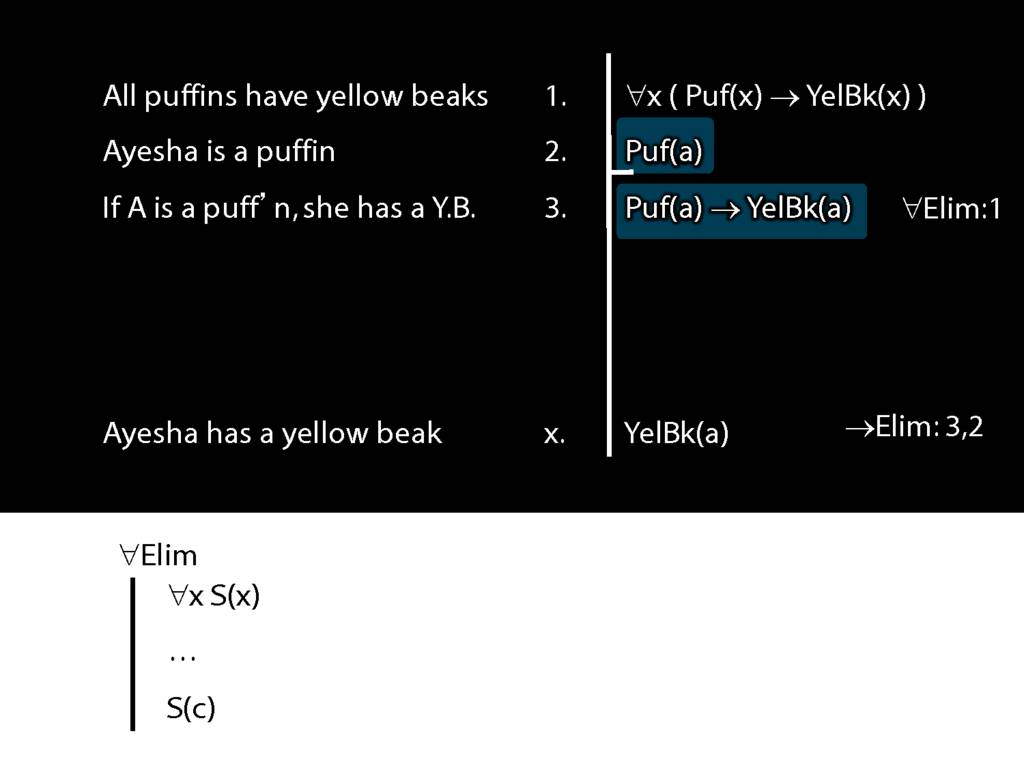

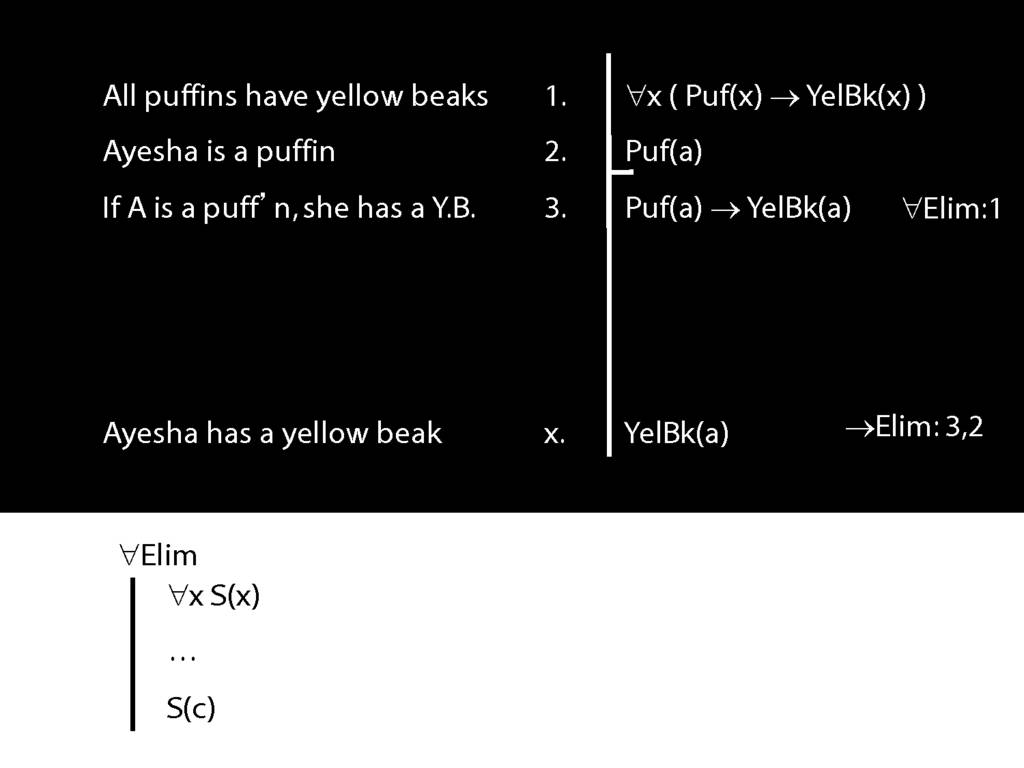

Now we have just what we need to get to the conclusion. But what's the rule and what lines should we cite?

It's arrow-elim and the lines we should cite are 2 and 3.

So far so good, ...

now for existential elim

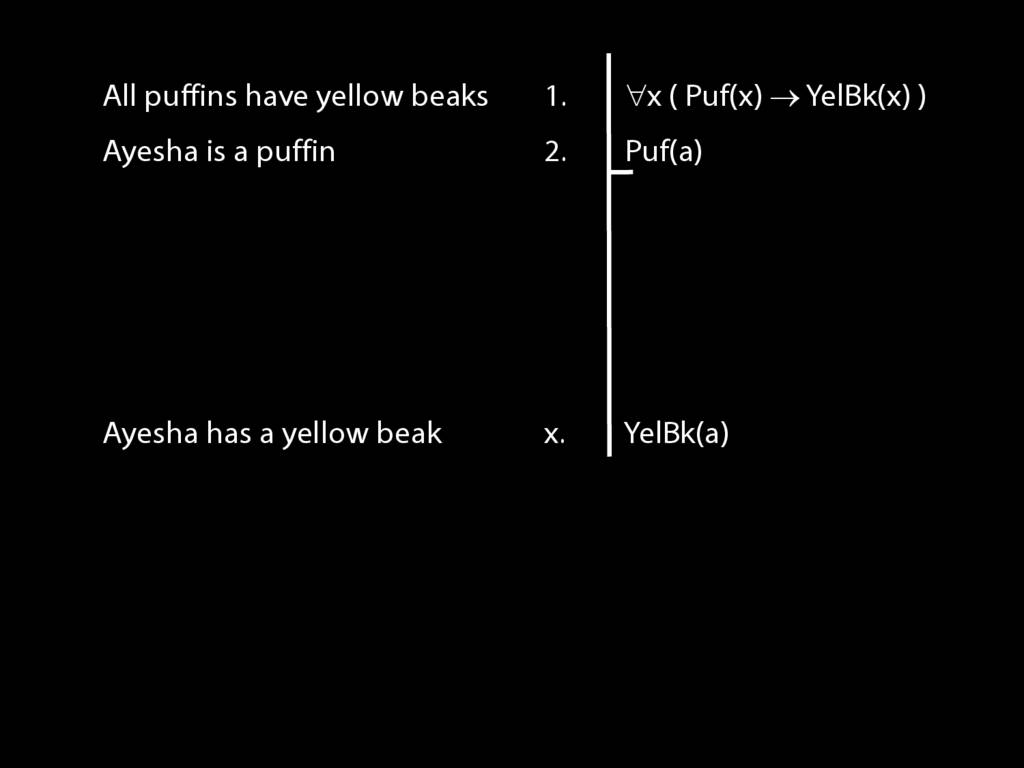

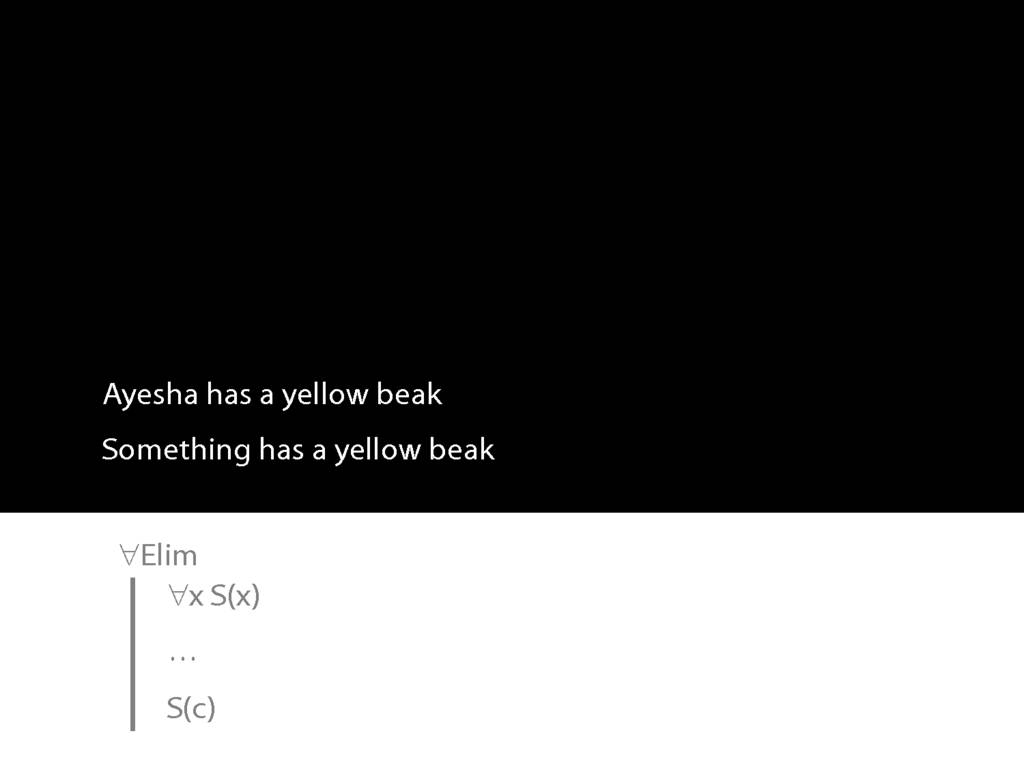

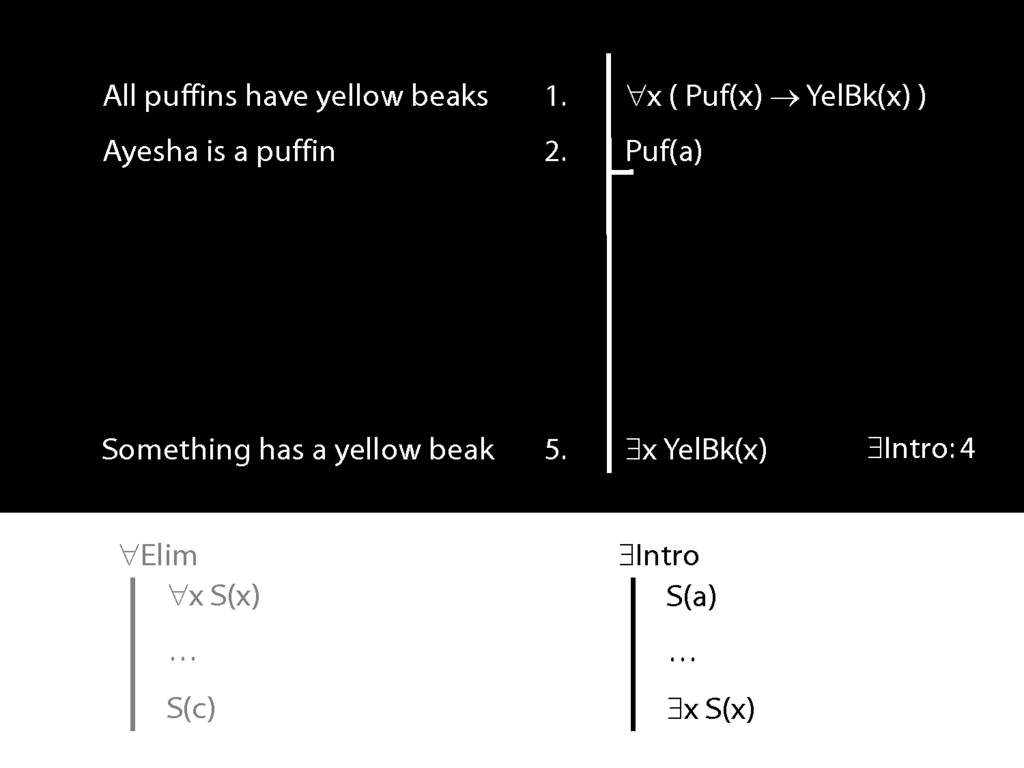

Here's some English

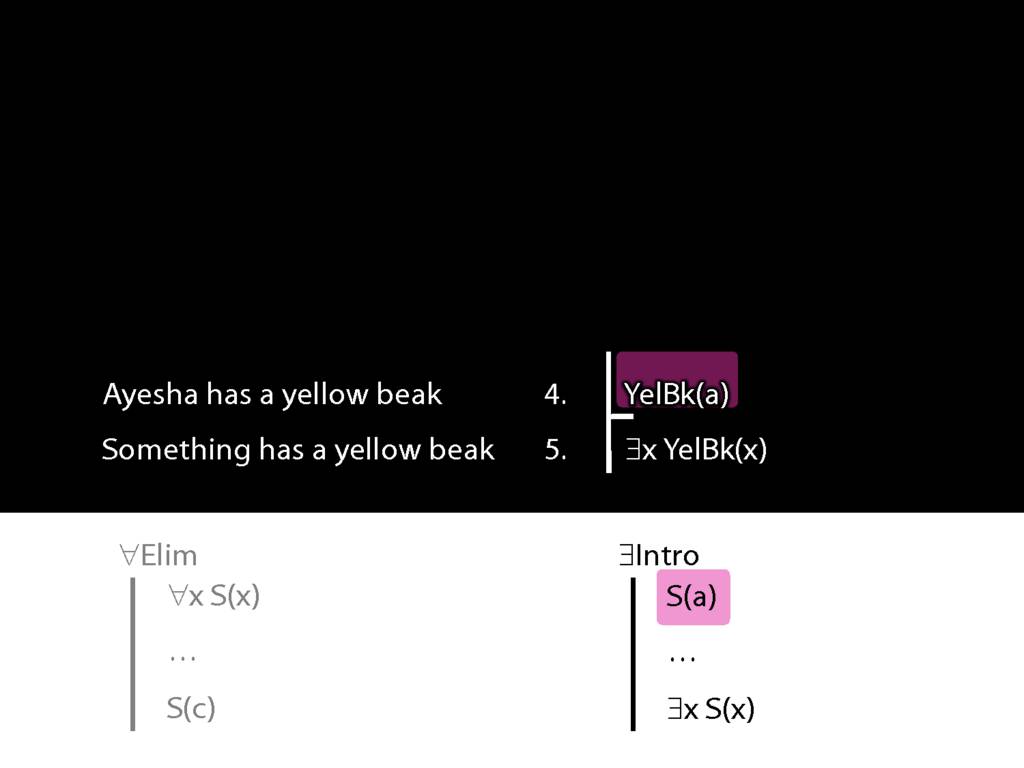

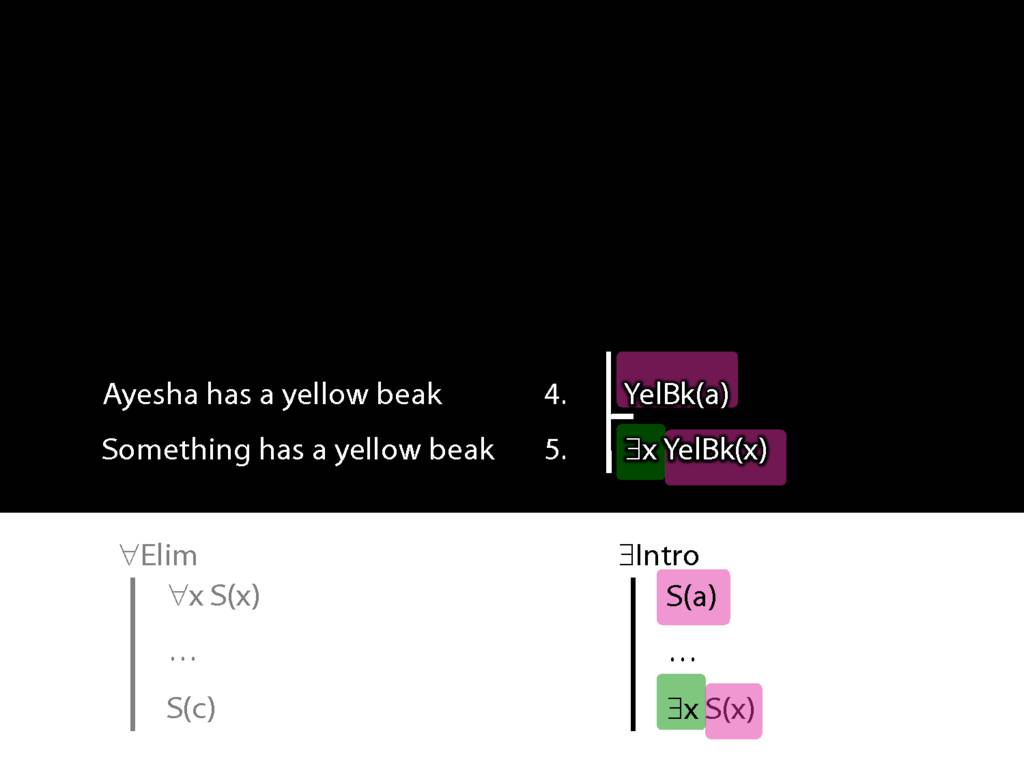

It's clear, I suppose, how we translate the premise. But what about the conclusion?

Well we're talking about something so we're going to need the existential quantifier.

But how can we prove this argument?

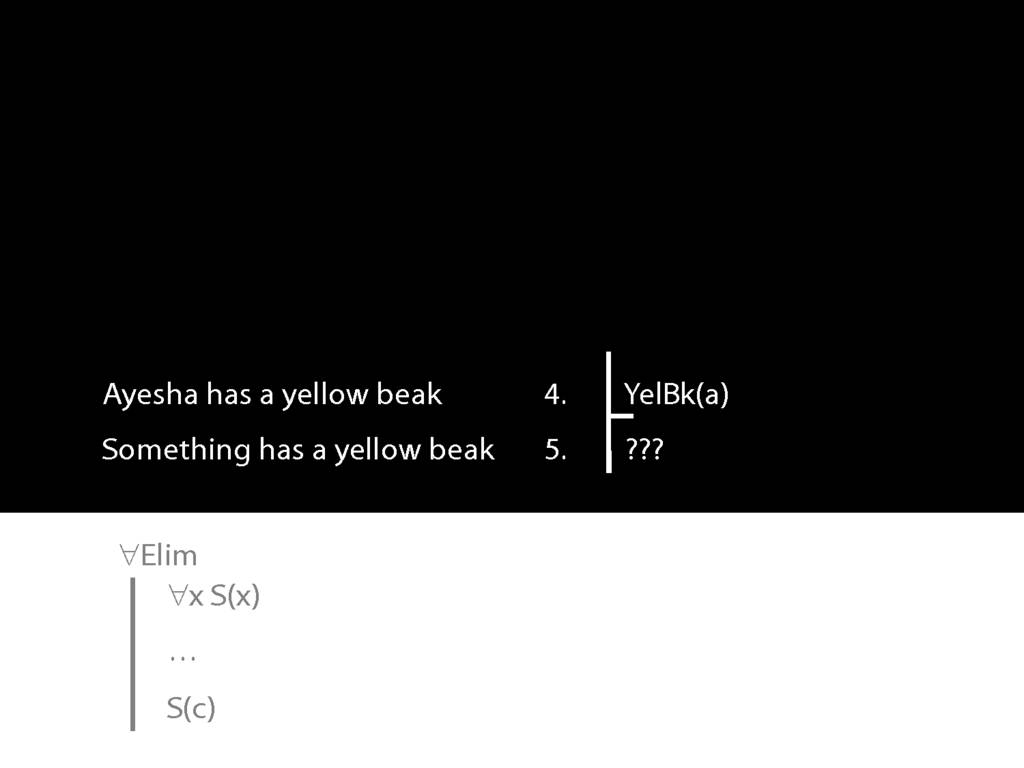

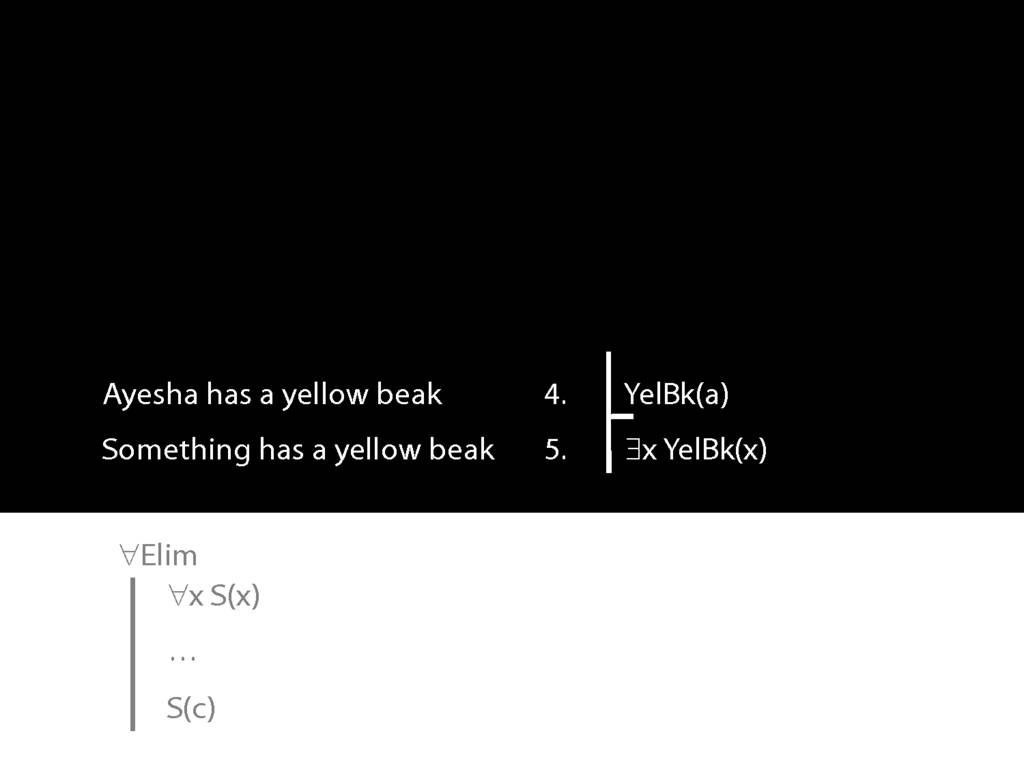

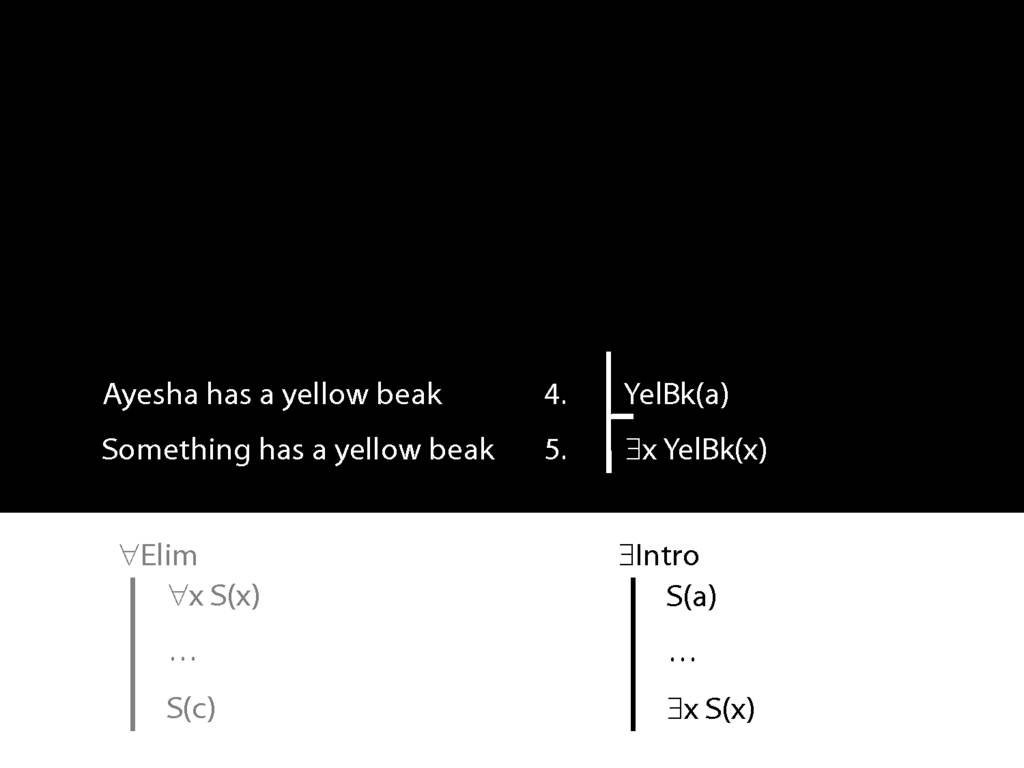

Well, that's just what the rule existential-intro is made for.

You have a statement about some named person, in this case about Ayesha.

You remove the name and replace it with a variable (here I've used x as the variable,

but you can use y or z or any variable you like),

and add an existential quantifier to the front.

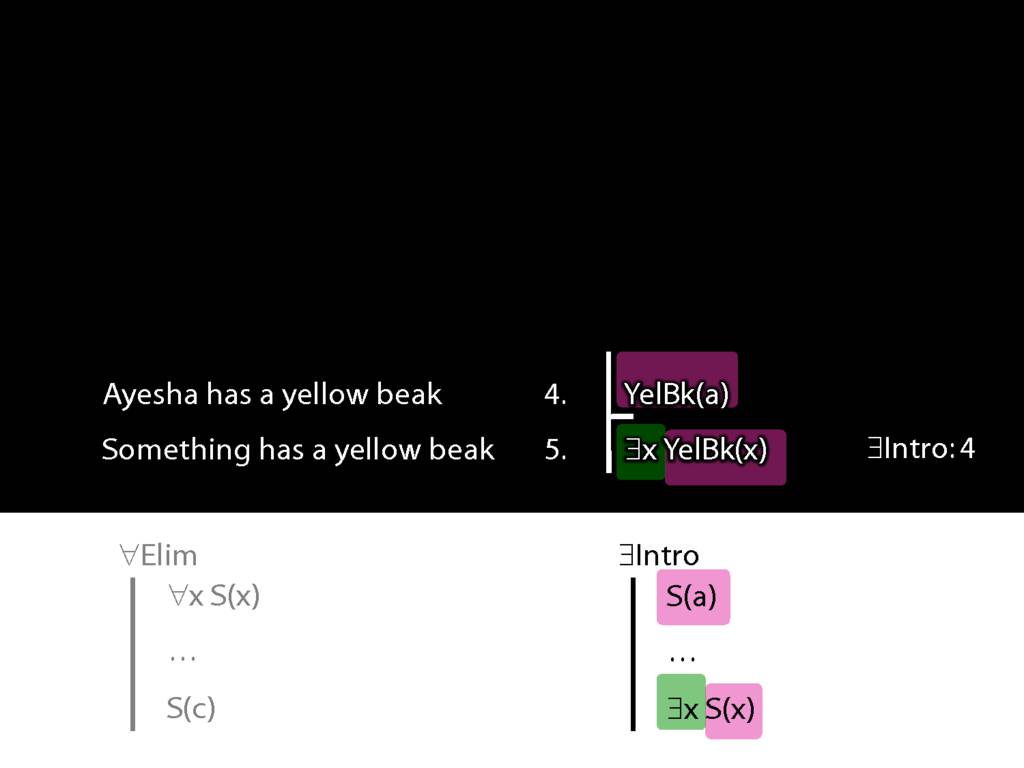

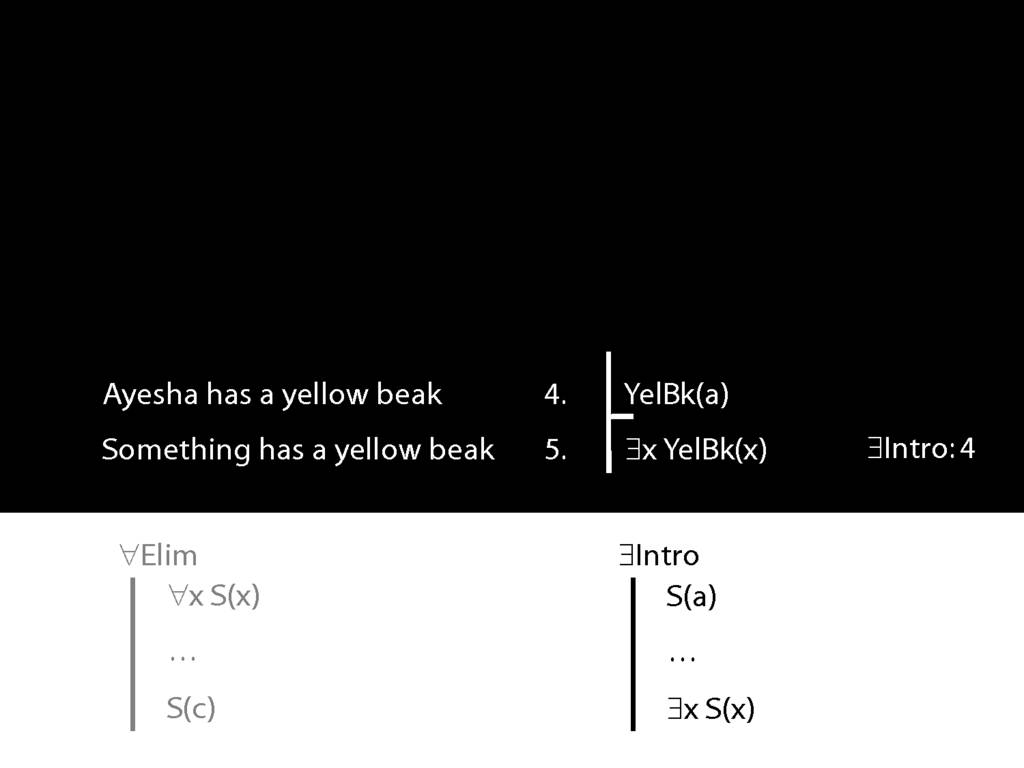

Of course we have to cite the rule and the line referenced, as always.

And that's it.

Now the premise of this argument is the conclusion of the argument we proved just a moment ago.

So we can join the two arguments together to make one big one.

Look, these premises allow us to prove this conclusion.

I know this maybe isn't the most exciting thing ever.

I'm just showing you so you can see how to get from universal to existential.

In case you ever need to.